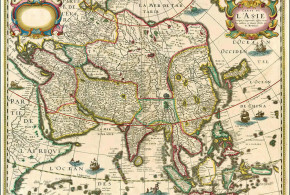

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The Portuguese language has been in relation to the trade and colonial expansion of Portugal the trade language of the Indian Ocean shores in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Portuguese was used, at that time, not only in the eastern cities conquered by the Portuguese but was also used ...

Read More »Portuguese Colonialism

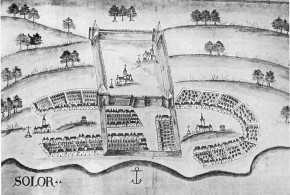

The Portuguese Fort on Solor Island, Indonesia

Written by Mark Schellekens. Photos by Mark Schellekens and Greg Wyncoll. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. On January 7th I paid a visit to the island of Solor off Flores’ north east coast. My main goal was to have a birdwatching trip on an virtually unknown island combined with a visit to the ruins of the fort. Solor is ...

Read More »The Portuguese on Solor and in the Lesser Sunda Islands

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. SOLOR AND THE LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS The early Portuguese contact with these islands was in the years about the 1520s. They frequented these islands mainly to purchase sandalwood. The early traders established only temporary warehouses. They did not build permanent trading posts, farms or fortresses, because this task was left ...

Read More »The Portuguese in the Moluccas: Ternate and Tidore

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. TERNATE AND TIDORE The first Portuguese expedition to the Moluccas under the command of António de Abreu arrived in Amboina and on the Banda islands in 1512. After an adventurous voyage he went back to Malacca. Francisco Serrão and other members of this expedition wrecked on a reef off Lucopino ...

Read More »Ambon: The Portuguese in the Moluccas, Indonesia

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Ambon is an island located in the south of the Spice Islands in what is today the Indonesian archipelago. In the year 1569 the Portuguese Gonçalo Pereira Marramaque erected a wooden fort on the northern coast of the Ambon island. In 1572 the fort was moved to the southern side ...

Read More »The Portuguese fort of Ternate

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The Portuguese fort of Ternate was founded by António de Brito in 1522, the foundation stone of the fortress was laid the day of the feast of St. John the Baptist, June 24, 1522, the fort was named “São João Bautista de Ternate.” The outer wall of the fortress enclosing ...

Read More »Makassar and the Portuguese

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The Kingdom of Makassar at the time of Portuguese expansion in the Asian seas comprised the two Kingdoms of Gowa and Tallo. Portuguese merchants frequented Makassar intermittently during the 16th century, but it was only after the Islamization of the Makassar Kingdom (1600s), that their presence grew. During the 17th ...

Read More »Portuguese Fort in Ende Island, Indonesia

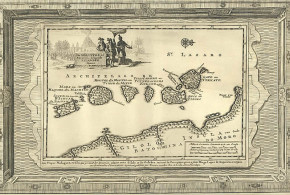

Written by Marco Ramerini. In 1595, the Dominican friars led by Brother Simone Pacheco built a little Fort on the island of Ende Minor (Palau Ende) to protect local Christians from Islamic attacks. This small fort was named by the Portuguese as Fortaleza de Ende. Pero Carvalhais was its first captain. Within the walls of the fort was built the ...

Read More »Population of the Portuguese Settlements in India

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Diu: (20°43’N – 71°00’E) Damão Grande or Praça de Damão (Damão, Moti Daman or Daman): (20°25’N – 72°50’E) 1634: 400 “almas entre portugueses e nativos cristãos”. Source: Leão “A Província do Norte do Estado da Índia” 1662: 100 “casais portugueses”. Source: Leão “A Província do Norte do Estado da Índia” ...

Read More »Goa: the capital of Portuguese India

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Goa is situated on an island at the mouth of the Mandovi River. At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in India, Goa was under the rule of the Sultan of Bijapur, for whom Goa was the second most important city. It was wealthy and possessed a grand ...

Read More »The Portuguese in Cochin (Kochi), India

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The city of Cochin (today: Ernakulam) was from the 24 December 1500, when the first Portuguese fleet called on its port, a firm ally of the Portuguese. The admiral of this fleet was Pedro Alvares Cabral (the discoverer of Brasil). The Rajah (king) of Cochin allowed, a “feitoria” (factory) to ...

Read More »Chaul a Portuguese town in India

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The Portuguese town of Chaul lies about 350 kilometers north of Goa and 60 kilometers south of Bombay (Mumbai) at the mouth of the Kundalika river near the village of Revdanda. Chaul was located on the low northern bank, opposed to a promontory on the south bank, which is called ...

Read More »The Portuguese in Bassein (Baçaim, Vasai): the ruins of a Portuguese town in India

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Bassein-Vasai (Baçaim) is situated at about 70 kilometers north of Bombay on the Arabian Sea. It lies on an island at the mouth of a river and was thanks to this position easily defensible. The city, which belonged to the Kingdom of Cambay, was a very important one before the ...

Read More »The Portuguese on the Bay of Bengal

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. On the Bay of Bengal there was a rather peculiar form of Portuguese settlements. Indeed this coast was not conquered militarily like the Malabar coast, but was colonized pacifically by groups of “Casados” (married men of the reserve army), beginning in the 1520s. SÃO TOMÉ DE MELIAPORE (Madras) The main ...

Read More »The forts of Salvador (Bahia)

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Right from the founding of the city the Portuguese started with the construction of a defensive system against foreign invasions, which occurred until the 18th century. The main works of fortification were executed after the Dutch conquest of the town (1624-1625) and the successive reconquest by the Portuguese. Fearing another ...

Read More »Salvador (Bahia): the capital of Colonial Brazil

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The Florentine Amerigo Vespucci, on 1 January 1502, came to a gulf at 13° latitude south, to which he gave the name Bahia de Todos Santos, on the shores of which the city of Bahia now stands. Salvador was founded in 1549 by Tomé de Souza, the first governor-general of ...

Read More »Recife Forts: Fort do Brum, Fort das Cinco Pontas

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. FORTE DO BRUM One of the most important remains of the Dutch rule in northeast Brazil is the Forte do Brum (Fort de Bruyne), on the northern end of Recife island. The fort was originally started to built in 1629 by the Portuguese, when the Dutch took control of Pernambuco ...

Read More »Recife: the capital of sugar cane of Colonial Brazil

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Recife is now the capital of the Brazilian state of Pernambuco. Until the 17th century the city was a small village near the capital of the Capitania of Pernambuco, Olinda. In 1630 with the Dutch conquest of northeastern Brazil, Olinda was burned by the Dutch, just because it was considered ...

Read More »Governors and Viceroys of Portuguese Brazil, 1549-1760

Written by Marco Ramerini. Brazil was discovered, almost by accident in 1500 by a Portuguese expedition live in the East under the command of Pedro Alvares Cabral. Cabral ‘s expedition followed the sea route to India traveled recently by Vasco da Gama, sailing around Africa. The expedition – to avoid the equatorial calms – followed a route far from the African coast ...

Read More »Olinda: a UNESCO World Heritage site in Brazil

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The city of Olinda, which is located a few kilometers north of Recife, was founded by the Portuguese in 1535 and was one of the first settlements founded by Europeans in Brazil. At the beginning of the 17th century the city became the capital of the capitania of Pernambuco, but ...

Read More » Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History