Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Igarassu (Igaraçu) is a beautiful little village situated 30 km north of Recife. In 1535 the Portuguese Duarte Coelho landed on this place to occupy his captaincy, donated by the Portuguese Crown. Duarte Coelho installed a stone mark, functioning as a dividing spot between the captaincies of Pernambuco and Itamaracá. This ...

Read More »Portuguese Colonialism

Paraty a Colonial Town in the state of Rio de Janeiro

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The main attraction of Paraty is its historic center with beautifully preserved colonial architecture. It is a day trip from the city of Rio de Janeiro. The distance is 240 km and it takes 4 hours to reach Paraty with a car along the beautiful coast of the Costa Verde, ...

Read More »Colonia del Sacramento: a Portuguese Fortress on the River Plate (Río de la Plata)

Written by Marco Ramerini. Photos: by Pedro Gonçalves. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. In 1680 the Portuguese founded along the northern bank of the River Plate (Río de la Plata/Rio da Prata) opposite Buenos Aires the fortress of Colónia do Sacramento (today Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay). The city was of strategic importance in resisting to the Spanish. Spaniards conquered ...

Read More »The Jesuit Missions in South America: Jesuits Reductions in Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Geoffrey A. P. Groesbeck The Indios Guaraní of Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil would have been another indigenous people victim of the colonial conquest in South America, if the Jesuits would haven’t been able to persuade the King of Spain to grant that vast region to their care. The Jesuits promised to the King ...

Read More »Kilwa: a Portuguese Fort in Tanzania

Written by Marco Ramerini. Photos by Alan Sutton Situated along the coast of Tanzania, Kilwa fort was built by the Portuguese in 1505 and was the first stone fort built by the Portuguese along the coast of East Africa. The construction of the fort was the work of the sailors and soldiers of the squadron of D. Francisco de Almeida, ...

Read More »The Fortress of Santo António da Ponta da Mina, Principe Island

Written by Marco Ramerini, photos and information by James Leese. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. According to a source dated 1815, this was the situation of the Portuguese forts on the island of Príncipe, in particular in the Bay of San António, where almost all the boats anchored: the two main defenses of the bay were the fortress of ...

Read More »The revolt of the slaves on the African island of São Tomé 1595

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The revolt of Amador, named after the slave who led it, is the most important attempt of rebellion that has ever happened on the island of São Tomé. The revolt of the slaves of the island began on July 9, 1595. The leader of this revolt was from the beginning ...

Read More »The Dutch on São Tomé and Principe: the attacks on the island of Principe (1598) and São Tomé (1599)

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. Shortly after the Union of Spain and Portugal, Philip II imposed the ban on the Dutch to trade and use the Iberian ports, this act was the result of the Dutch rebellion against the Spanish king, and it suddenly kept the Dutch away from the supply of goods from the ...

Read More »A Portuguese fort in Madagascar: the fort near Tolanaro

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The big island of Madagascar was discovered in 1500 by a Portuguese fleet under the command of Diogo Dias, which was part of a fleet of 13 ships commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral. The Portuguese called the new discovered island Ilha de São Lourenço. The island was visited several times ...

Read More »Data on the independence of Portuguese colonies

Written by Dietrich Köster. Brazil – 07 September 1822 Cape Verde – 05 July 1975 Portuguese Guinea – unilateral proclamation: 24 September 1973, definitive independence: 10 September 1974 São João Baptista de Ajudá – occupation by the Republic of Dahomey (Benin): 01 August 1961 São Tomé and Príncipe – 12 July 1975 Angola – 11 November 1975 Mozambique – 25 ...

Read More »African Countries with Portuguese as an Official Language

Written by Dietrich Köster © June 2012 by Dietrich Köster, D-53113 Bonn Cape Verde Official name: Republic of Cape Verde Capital city: Praia Language: The official language is Portuguese, besides Creole is spoken. Population: 530,000 Area: 4,036 sq km Currency: Cape Verde Escudo (CVE) Independence Day: 05 July 1975 Guinea-Bissau Official name: Republic of Guinea-Bissau Capital city: Bissau Language: The official ...

Read More »Portuguese language heritage in Africa

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. After the conquest, in 1415, of the Arab stronghold of Ceuta in Morocco, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to explore the African coast, and in the 1460s they built the first fort in Arguin (Mauritania). 1482 was the year of the construction of São Jorge da Mina Castle on ...

Read More »Portuguese fortresses of Luanda

Written by Marco Ramerini. Photos by Virgílio Pena da Costa. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. The city of Luanda, the capital of Angola, was founded by the Portuguese explorer Paulo Dias de Novais on 25 January 1576. The city was named by the Portuguese as “São Paulo da Assumpção de Loanda”. The Portuguese, in the following years, built three ...

Read More »Fort Jesus Mombasa: a Portuguese fortress in Kenya

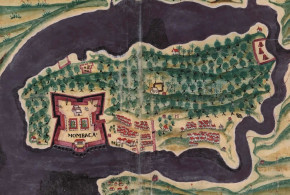

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. In 1498 the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in Mombasa on his route to India. Fort Jesus was built after the Portuguese had become masters of the East African coast for nearly a hundred years. During this time they had as main base an unfortified factory at Malindi. The ...

Read More »The European forts in Ghana

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. FORT SÃO JORGE DA MINA (ELMINA) The first European-built fort in Ghana was Fort São Jorge da Mina (Elmina), which was built by the Portuguese in 1482 near an African village, with which they traded, called by them Aldeia das Duas Partes. The foundation stone of this castle was laid ...

Read More » Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History