Written by Marco Ramerini, 2005-2021 (English translation: 2023) General index THE FAILED EXPEDITIONS TO ALGIERS 3 FIRST EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS 4 SECOND EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS 9 THE MOLUCCAS 10 THE CONQUIST OF TERNATE AND THE MOLUCCAS 10 THE EXPEDITION TO MALACCA 15 THE PHILIPPINES 18 THE YUCATAN 20 FIRST TERM OF GOVERNOR 20 SECOND TERM OF GOVERNOR 22 THE WIDOW ...

Read More »Spanish Colonialism

The peripheral forts of the Spaniards in the Moluccas (1606-1677)

Written by Marco Ramerini, 2005 (English edition: 2023) In this text I describe the information I have gathered over the years regarding the Spanish outposts in the peripheral islands of the Moluccas, therefore excluding the islands of Ternate and Tidore. Spanish control, in fact, was not limited only to the two main islands of Tidore and Ternate, which are treated ...

Read More »Esteban de Alcázar, a soldier in the service of the king of Spain in Europe, the Philippines and the Moluccas

Written by Marco Ramerini – 2021 (English translation: 2023) General Index AROUND EUROPE p. 3 ARAGON, ITALY, FRANCE p. 3 FLANDERS, FRISIA, GELDRIA… p. 4 THE RETURN TO SPAIN p. 7 IN THE PHILIPPINES AND THE MOLUCCAS p. 10 THE CONQUEST OF TERNATE p. 10 THE FIRST BATTLE OF PLAYA HONDA p. 11 PERMANENCE IN TERNATE p. 11 THE WEDDING ...

Read More »Tidore 1 – The Spanish forts on the island of Tidore 1521-1663: introduction

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This research aims to want to shed light on an aspect of the history of the Moluccas islands that is still largely unexplored. Its purpose is to trace through the study of manuscripts and other documents a preliminary framework of the fortifications, the Spanish had built on the ...

Read More »Tidore 2 – The expeditions of Magellan and Villalobos: The first contacts of the Spaniards with the island of Tidore and the first Spanish fort

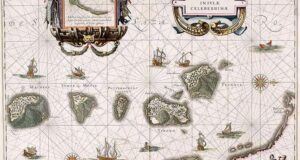

Written by Marco Ramerini – 2000-2007/2023 2 – THE EXPEDITIONS OF MAGELLAN AND VILLALOBOS: THE FIRST SPANISH CONTACTS WITH THE ISLAND OF TIDORE AND THE FIRST SPANISH FORT In the first half of the sixteenth century, upon the arrival of the Europeans, two main kingdoms competed for control of the Moluccas islands, they were the Ternate sultanate and the kingdom ...

Read More »Tidore 3 – The Spanish expeditions to the Moluccas after the union with Portugal

Written by Marco Ramerini – 2000-2007/2023 3 – THE SPANISH EXPEDITIONS TO THE MOLUCCAS AFTER THE UNION WITH PORTUGAL The first period of interest of the Spaniards in the Moluccas, i.e. the one concerning the years 1521-1606, can be divided into two distinct parts: the first part was that, to which we have already mentioned, of the struggles against the ...

Read More »Tidore 4 – The Spanish forts on the island of Tidore, 1606-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster. 4.0 THE SPANISH FORTS ON THE ISLAND OF TIDORE, 1606-1663 As we mentioned earlier, from April 1606 after the conquest by the troops of Acuña of the city of Ternate, the Spaniards had, in the Moluccas, as their main and often the only ally the King of Tidore. They tried for ...

Read More »Tidore 5 – The defenses of the city of the King of Tidore: Lugar Grande de El Rey (Soa Siu) and the fort of Gomafo. The Spanish fortresses on the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 5 – DEFENSES OF THE CITY OF THE KING The centerpiece of Tidore’s defenses were the fortifications of the island’s main city, which the Spanish called Lugar Grande del Rey. It was located on the southeast coast of the island, where today is the main city of Tidore, Soa Siu. Over the years, a series ...

Read More »Tidore 6 – Fuerte de los portugueses (Fortaleza dos Reis Magos). The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 5.2 – FUERTE DE LOS PORTUGUESES Fuerte de los Portuguéses (Fortaleza dos Reis Magos): (Current name: ?) CHRONOLOGY: Portuguese: January 6, 1578 – May 19, 1605 Captured by the Dutch on 19 May 1605 then abandoned. Spanish: c.1609 – 9 July 1613 Dutch: 9 July 1613- August/November (?) 1613 This is the fort built in ...

Read More »Tidore 7 – Tohula Fort, Santiago de los Caballeros. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 5.3 – SANTIAGO DE LOS CABALLEROS (TOHULA) Tohula1, Santiago de los Caballeros2, Sanctiago de los Caualleros3, Tahula, Taula, Thaula Olandese: Tahoela4, Tahoelo5, Tahoele6: (Current name: Benteng Tohula) CHRONOLOGY: Spanish: The construction of this fortress was begun by Azcqueta, in 1610, the works were resumed more intensely starting from 1613, it was finished by Geronimo de ...

Read More »Tidore 8 – Sokanora Fort. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 5.4 – SOKANORA Sokanora, Socanora1, Sokanosa, Saconora2, Zoconora3: (Current name: ?) CHRONOLOGY: Spanish: 1613-c.1620 (?) Socanora, was a village located on the coast to south of the city of the king of Tidore (‘Lugar Grande‘). Here the Spanish maintained a small fortified post for some years. We already have a first mention of the village ...

Read More »Tidore 9 – The Fort of Marieco. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 6 – WEST COAST AND NORTH COAST OF THE ISLAND On the western coast of Tidore the Spanish had garrisons in the localities of Marieco, Rume, Tomañira (which was almost certainly the same fort sometimes also called Marieco el Chico) and finally in the extreme northern tip at Chobo. This part of the island which ...

Read More »Tidore 10 – Tomanira Fort. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 6.2 – MARIECO EL CHICO OR TOMANIRA Spanish: Marieco el Chico: Dutch: Kleine Marieko, Spaens Mariecque. This fort was built by Geronimo de Silva in 1613, after the loss of Marieco (Marieco el Grande), and was located half a league from Marieco. After the conquest of Marieco by the Dutch, Geronimo de Silva describes in ...

Read More »Tidore 11 – Chobo Fort. The Spanish fortresses on the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 6.3 – CHOBO Spanish: Cubo1, Sobo2, Chobo3, Chovo4, Cobo, Tjobo, San(t) Joseph de Chouo5: (Current name: Cobo) CHRONOLOGY: Spanish: 1643 ? –1661 ? o 1662 ? Dutch: Chiobbe6, T’Siobbo7, Siobbo8, Ziobbo9, Tsiobbe10, t’Siobbe11, Sjobbo12, Sjobbe13 Spanish garrison located on the extreme northern offshoot of the island of Tidore, called by the Spaniards San Joseph de Chovo. ...

Read More »Tidore 12 – The Fort of Rume. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 6.4 – RUME Spanish: Rume, Rum, Rumen1, El Rume, San Lucas de el Rume, San Lucas del Rumen2: (Current name: Rum) CHRONOLOGY: Spanish: November 1618-May/June 1663 Dutch: Roemy3, Roumy4, Romi5, Roumi6, Roemij7, Roumij8, Roemi, Romy9 A mention of the port of Rume was already made in 1585 in the report of the friar Cristoval Salvatierra: ...

Read More »Tidore 13 – Puli Caballo Island. The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini 2000-2007/2023 6.5 – PULI CABALLO Spanish: Puli Caballo: Sant Miguel de la isla de Puri Cauallo (Puli Cauallo) (Current name: Pulau Mare) CHRONOLOGY: Spanish: c.1650 ?-1662 ? Dutch: Pottebackers Eyland The island in question is a small island located south of Tidore, according to what de Clercq tells us, the name Mare meant ‘stone‘ both in ...

Read More »Tidore 14 – Captains of Tidore (Fortress of Santiago de los Caballeros). The Spanish fortresses in the island of Tidore 1521-1663

Written by Marco Ramerini. 2000-2007/2023 7 – CAPTAINS OF TIDORE (Fortress of Santiago de los Caballeros) In Tidore resided a Spanish captain who commanded the garrisoned troops in the ‘presidios‘ of the island and who also had under his jurisdiction the garrisons of Payaye and Tafongo located on the island of Halmahera and during the period in which the Spanish ...

Read More »Documentary about Moluccas: The Spice Odyssey – The Moluccas Islands

When the fifth centenary of the first trip around the world (1519-1522) is commemorated, the ultimate goal of which was to reach the Moluccas Islands and obtain access to the spices of these islands for the Spanish crown, the documentary The Odyssey of the Spices is presented. This historical documentary, off approximately 55 minutes, is a co-production of Atrevida Producciones ...

Read More »Manila Galleon and the Spice Route

Colloquium on the Manila Galleon and the Spice Route, organized by the Indonesian Hidden Heritage Creative Hub, with the collaboration of the embassies of Spain, the Philippines and Mexico in Indonesia. Saturday 20 May 2023 – Museum Bahari – Jakarta – Indonesia Colloquium on the Manila Galleon and the Spice Route

Read More »San Rafael de Velasco mission, Chiquitania, Bolivia

Written by Geoffrey A. P. Groesbeck San Rafael de Velasco, the second oldest mission settlement in the Chiquitania, was established in 1696 by the Jesuit missionaries Juan Bautista Zea and Francisco Hervás (each of whom later co-founded two other missions). It was settled largely as what was then anticipated as an eventual way stop along the road to other Jesuit ...

Read More » Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History