This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Written by Marco Ramerini, 2005-2021 (English translation: 2023)

General index

THE FAILED EXPEDITIONS TO ALGIERS 3

FIRST EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS 4

SECOND EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS 9

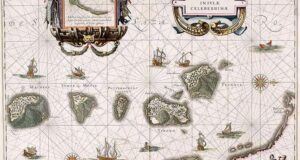

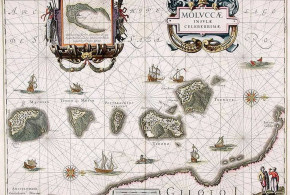

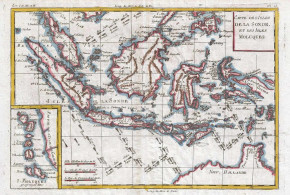

THE MOLUCCAS 10

THE CONQUIST OF TERNATE AND THE MOLUCCAS 10

THE EXPEDITION TO MALACCA 15

THE PHILIPPINES 18

THE YUCATAN 20

FIRST TERM OF GOVERNOR 20

SECOND TERM OF GOVERNOR 22

THE WIDOW OF MALDONADO: ISABEL DE CARABEO 23

BIBLIOGRAPHY 27

DOCUMENTS 27

In my research on the Moluccas I have often come across characters who have traveled the world in the service of Spain, facing dangers and risks to serve the king, their faith and to get rich. One of them is undoubtedly Fernando Centeno Maldonado, who served the Spanish crown for over forty years. In fact, he began his career in 1601 by participating in the failed expedition for the conquest of Algiers, the following year, still unsuccessfully tried the same adventure.

Then, in 1604, he embarked from Spain (Seville) together with the company of Juan de Esquivel directed first to Mexico, then to the Philippines and finally to the Moluccas. And it is here that I met him for the first time in my researches, when in 1606 he participated in the conquest of Ternate. Maldonado in later years served the King of Spain in the Moluccas and the Philippines. In 1616 he also participated in Juan de Silva’s expedition to Malacca.

After moving to Mexico, Maldonado was appointed Governor and Captain General of the Province of Yucatán twice (1631-1633 and 1635-1636) by the Viceroy of New Spain. Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado died in 1636, at the end of his second term as governor of the Province of Yucatán.

THE FAILED EXPEDITIONS TO ALGIERS

Fernando Centeno Maldonado participated as an adventurer in the “jornadas” of “Arzel” (Algiers) which were led by Prince Andrea Doria and Don Juan de Cardona.1 These are two expeditions, or better expeditions attempts which had as their objective the conquest of the city of Algiers in North Africa. At the time, Algiers was a den of pirates who attacked the ships of the navies of the European countries that sailed the waters of the Mediterranean. These attacks by pirates caused serious damage to merchant trade in the Mediterranean. The main bases of these pirates were located along the Mediterranean coast of northern Africa, and were the cities of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli.

The vessels of the King of Spain were among the main targets of these raids. So Spain repeatedly tried to get rid of this problem by organizing expeditions aimed at the conquest of their strongholds. In two of these expeditions, as we have written, according to some documents, it seems that Fernando Centeno Maldonado also took part. There is an interesting historical source on the first expedition mentioned by Fernando Centeno Maldonado.2 It is a 26-page document by a Genoese historian (Gerolamo De Franchi Conestagio, or Gerolamo Franci Conestaggio 1530-1617), one of the few that seems to deal with this expedition. The original title is “Relatione dell’apparecchio per sorprendere Algieri” and was published in Genoa on November 5, 1601, therefore only a few months after the events.

FIRST EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS

According to the document, in 1601, the King of Spain Philip III sent a fleet made up of 70 galleys and an army of over ten thousand men, under the command of Prince Gian Andrea Doria, also known as Andrettino Doria and in Spanish documents as Juan Andrea Doria (1539-1606). Gian Andrea Doria was a Genoese admiral, great-grandson of the famous Andrea Doria (1466-1560). During his life Gian Andrea Doria participated, in the service of Spain, in various campaigns against the Turks and Berbers in the Mediterranean, among these, the most famous was that of Lepanto in 1571. Among his titles are those of commander of the Order of Santiago, Marquis de Tursi and “Príncipe de Melfi”.

According to the story it all began two years earlier (therefore in 1599), when a Frenchman, called “il Capitano Roux“, presented himself to Prince Doria who was then Captain General of the King of Spain’s armies. This Frenchman had been the one who, in recent years, had commanded the Grand Duke’s galleys in the Archipelago. Being well informed on the affairs of the Barbary Corsairs, he tried to convince the prince that it would be very easy to take the city of Algiers from the Turks. The reasons that the French captain reports to Gian Andrea Doria to strengthen his idea that the taking of the city would have been easy are the following: 1) the city guard was neglected, because the defenders relied on the power of their fortifications, leaving the defenses unmanned. In mid-June, the janissaries defending the city, which usually consisted of seven to eight thousand Turks, began to leave Algiers to collect tribute from the various villages in the interior of the country. In this period, only about two thousand soldiers remained in defense of the city. According to the French captain, the Turkish soldiers have an obligation to return in September, therefore he judges August to be the best month for an attack, he is certain that in August he will find the city almost devoid of defenders.3

In addition to this, during this month, most of the citizens are on their properties, busy harvesting and the corsairs in this period leave to raid the coasts with their galleys. According to Captain Roux, four ships loaded with weapons and soldiers, disguised as merchant ships, would have been enough to enter the small port. At this point the attackers would have called the Christian slaves, who were still in large numbers in Algiers, to rebellion: this was the substance of his reasoning.4

Gian Andrea Doria, who did not know the man with whom he was dealing very well, doubted the accuracy of his statements, but nevertheless, it seemed to him that there was something good in this project. In fact, he believed that with little risk it would have been possible to have a great result. He then began to make the first preparations. He sent the French to Spain to explain his plan to the king. To clarify his doubts, he also sent an emissary to Algiers (who, however, was kept in the dark about the reasons for his mission) to gather information and to understand if what the French had said was true.5

After being heard in Spain, Captain Roux was sent back to Gian Andrea Doria. The King of Spain ordered Gian Andrea to prepare for the enterprise against Algiers. The undertaking was to be secret and even the prime ministers themselves were not to be informed. Gian Andrea Doria’s first move, since the Frenchman was very talkative and did not consider him capable of keeping a secret, was to dismiss the French captain a few days after receiving the order to prepare the expedition, telling him that his plan was attractive, but that the king could not risk his troops in so uncertain an enterprise, the French departed, having received a reward.6

So Gian Andrea Doria looked for a Spanish soldier, with war experience, to send him to Algiers to do further research and to get more reliable information. To this end, he chose Antonio de Rojas, ensign of Inigo Borgia, mestre de camp in Lombardy. Antonio de Rojas was sent to Algiers where he observed the situation in the city. After the visit to Algiers the Spaniard had orders to go from there to Spain, and to report to the king everything he had seen. This man, having fulfilled his mission, made a report on his return which greatly increased the king’s desire to attempt the capture of Algiers. Indeed Antonio de Rojas in his account confirmed that in August the city was poorly defended.7

At this point Gian Andrea Doria began preparations for the expedition, as we will see it was not an easy task to coordinate everything. Putting together your own army, supplying it, managing soldiers and adventurers together and being able to do all this in great secrecy, was very difficult. The galleys of the king of Spain were few and some were in bad shape. Gian Andrea was forced to ask the Princes of the various Italian states to lend their fleets, the viceroys of Naples and Sicily were then ordered to prepare, not only the galleys and troops to be embarked, but also the necessary supplies and ammunition.8

The meeting point should have been the island of Majorca, but Gian Andrea did not want to go directly from Genoa to Majorca, but planned a longer itinerary so as not to make the Turks suspicious. It was decided to go from Genoa to Naples and then to Sicily. From Sicily the fleet would go to Majorca. It was decided that part of the Spanish troops were to embark in Naples and Sicily, together with some Italian soldiers. The King of Spain, in early 1601, had assembled a large army near Milan, to come to the aid of the Duke of Savoy, then at war with the King of France. But later France and Savoy had agreed and therefore the Spanish army in Milan was no longer needed. Gian Andrea Doria took the opportunity to request and obtain some regiments to join the expedition he was preparing.9

The fleet embarked part of the soldiers on June 27 from Genoa. Initially it was made up of Spanish and Italian soldiers who had come from Milan and were embarked on the galleys commanded by Carlo Doria, son of Gian Andrea. Gian Andrea left on July 4 with the ‘Reale’, five galleys from the Pope, six from the Republic of Genoa, four from the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and the rest of the troops. The fleet arrived in Naples on July 15, and remained here until the 17th. The boats continued to Messina where they arrived on July 19. Both in Naples and in Messina other boats had to join, but this did not happen. In fact, the orders of the King of Spain and those of Gian Andrea had been disobeyed. The Neapolitans had sent the galleys of their fleet to the Levant from where they returned in need of many repairs. It was found that the number of galleys from Sicily to join the expedition had decreased rather than increased. While the boats that were supposed to arrive from Spain arrived so late that they would not have arrived in time to leave if the others had obeyed the orders given. The expedition therefore suffered numerous delays, the document details the problems faced in the organization and coordination to be able to collect many boats from different places in the same point.10

However, on July 19 most of the fleet reached Majorca. The fleet consisted of seventy galleys: La Reale with sixteen boats from the Genoa squadron and two from the Duke of Savoy in the pay of the King, all commanded by Carlo Doria, Duke of Tursi, their general. Other sixteen galleys were those coming from Naples commanded by Pedro de Toledo. Twelve galleys arrived from Sicily, nine of which belonged to the King and three to the Duke of Macheda, led by Pedro de Leïva. Then there were eleven galleys from Spain, commanded by the Count of Buendia. Five galleys had been supplied by the Pope and were under the orders of Commander Magnolotto, his lieutenant. Six galleys were supplied by the Republic of Genoa, under the orders of Count Gio, with General Tommaso Doria. Finally four galleys were supplied by Tuscany commanded by Marco Antonio Calafatto, admiral of the galleys of the Order of Santo Stefano. Of all this fleet the galleys from Naples, Sicily and Spain were in poor condition, lacking rowers, and in Majorca it was necessary to crew rowers from one of the squadrons so that they would be adequately supplied..11

The soldiers numbered more than ten thousand. The army was made up of Spanish soldiers, of which 600 came from Lombardy, commanded by Jnigo Borgia; 1,000 soldiers arrived from Brittany, commanded by Pedro de Toledo de Anaya; 2,000 soldiers arrived from Naples, commanded by Pedro Vivero; 200 soldiers arrived from Sicily commanded by Salazar Castellano from Palermo; 500 soldiers were those of the army of Governor Antonio Quinones. Then there were 2,500 Italian soldiers, under the orders of Barnaba Barbo; and 1,500 soldiers of the battalion of the kingdom of Naples, under the command of the mestre de camp Annibale Macedonico. Furthermore, the Pope’s galleys had embarked 350 good soldiers and those of Tuscany about 400 soldiers. Furthermore, many Knights of Saint Stephen joined the expedition. Andrettino Doria had given the general command to his mestre de camp Manuel de Veda Capo di Vacca, an expert and courageous captain.12

There were also some adventurers in the army, probably among them our young Fernando Centeno Maldonado. The document mentions among the adventurers: the Duke of Parma, who, with two hundred knights, old soldiers from Flanders, embarked on Carlo Doria’s galley ‘Capitana‘. Among the most prominent characters are mentioned: Virginio Orsino, Duke of Bracciano, who was embarked on the galley ‘Capitana’ of Florence. While on the Royal galley, the Marquis of Elche, eldest son of the Duke of Macheda had embarked; Alo Idiaqués, general of the light cavalry of the State of Milan, chosen by Gian Andrea Doria as his lieutenant; Diego Pimentel, Manuel Mantiques, Grand Commander of Aragon, the Count of Celano, the Marquis de Garesfi, Ercole Gonzaga, Gio Geromino Doria, Aurelio Tagliacarne and a few other captains and worthy personalities, including seven or eight Roman gentlemen.13

Jeronimo Conestaggio’s document also informs us of the plans prepared for the attack. The fleet was supposed to sail together as far as Algiers, but stop at a sufficient distance not to be seen from land. At this point a group of three hundred arquebusiers should have landed in small boats on the coast and advanced to the city gate which is in the ‘Marina‘. Once the port was taken the rest of the army would have to disembark. In the event that the arquebusiers failed to take the port, the Royal Galley, along with fifteen other of the best galleys, were dispatched to assist them.14

On August 30, 1601, the armada arrived within sight of the African coast, but the fleet did not remain united, more than three hours had to be lost to assemble the fleet. The fleet landed thirty miles from the city. Gian Andrea Doria thought it appropriate to have the coast searched with small boats, in order to find a point closer to the city where there was an anchorage for large ships. The pilots in charge of reconnaissance of the coast did not return until evening, to the great anger of Gian Andrea who did not know what to think of the reason for such a delay. Yet this delay, which occurred at that moment, as well as being strange, proved to be fatal and decisive. When the pilots arrived they said that the currents had driven the boats eastward over 50 miles from Algiers, and they had been unable to get close to land.15

The next day, which was to be the day of the attack, all preparations were made. Everything was ready for the landing: the troops that were to strike the first blow, that is 300 Spaniards, had been embarked in the frigates and feluccas. Before dawn the fleet was twenty miles from land, it was then that the Greek wind began to blow from the Levant. It began to blow with such violence that it was not possible to land or stay in the open sea. The boats dispersed. The fleet assembled at Majorca on 3 September. But the contrary wind continued for several days, Gian Andrea Doria pondered what to do. Among the soldiers there were those who would have liked to return at any risk and despite the wind; while the more experienced sailors and soldiers, given the situation, were more judicious, knowing full well that it was not possible to sail or land with a headwind. Considering that the surprise effect had vanished, that it was already September and the Turkish militias had probably already returned in large numbers to the city and that food was starting to run low, Gian Andrea Doria, reluctantly, decided to cancel the enterprise.16

Jeronimo Conestaggio indicates disobedience and the loss of time caused by the galleys of Naples and Sicily as the real cause that prevented the successful outcome of the expedition. Perhaps it was the disagreements between the viceroys and the royal ministers that delayed the expedition. The only certainty is that the enterprise was a failure and Gian Andrea Doria, deeply disgusted by the intrigues and unjust accusations to which he had been subjected, was replaced by Don Juan de Cardona.17

SECOND EXPEDITION TO ALGIERS

In 1602, rumors spread that Don Juan de Cardona y Requesens would be put in command of an expedition against the pirates’ lair in Algiers, but this expedition never came true.18 Perhaps this expedition was also attempted, but unlike the one narrated above, are there no historical traces left? In Fernando Centeno Maldonado’s “Informaciones” this expedition is clearly mentioned: He participated as an adventurer in the Algiers expedition of 1602 (“en la jornada de Argel por abenturero“) which was under Don Juan de Cardona.19

Regarding this second expedition I found some information. The Spanish appear to have concentrated a considerable naval force at Cadiz for the purpose of accomplishing one of the three feats listed here: the invasion of England, a relief expedition to aid the rebels in Ireland and the capture of Algiers. “Su magestad anda con muy gan desseo de hazer una empresa en servicio a Dios y donde se gane reputacion conforme a la grandeza y valor de su Real animo, offrescensele agora tres, que son, la de Inglaterra, Irlanda y Arzel…” at first the Adelantado Mayor, Martín Padilla y Manrique, chose the invasion of England.

However, in May 1602, in the Puerto de Santa María in Cadiz, the Adelantado, Martín Padilla y Manrique died, the enterprise was thus taken over by Juan de Cardona, who due to the delays in the meeting of the boats in the Puerto de Santa María he was forced to give up the invasion of England and also the “socorro” to Ireland. It was therefore decided to use this large fleet of around 40 galleys for a surprise attack on Algiers.

Such an attack had been proposed to Philip III of Spain by what Spanish documents indicate as Benalcadi, Rey del Cuco, i.e. Amar ben Amar, king of an area of Algerian Kabylia near Algiers. However, the King of Spain in one of his letters dictated stringent conditions to implement the plan. The fleet must absolutely not be risked in landings or battles, but must be limited only to giving support to the king of Cuco who must do a large part of the enterprise. Then, once the city was taken, the Spaniards had to help the king of Cuco to control it. Due to the delays in the preparations in the port of Cartagena it was then decided to change the target, no longer Algiers, but Buja (Béjaïa), another coastal city of Algeria that the Spaniards had already occupied between 1510 and 1555. The fleet then moved on to Mallorca where the two options were again considered. But lacking the guarantees for a favorable outcome, it was decided to disperse the fleet and abandon the expedition.20

THE MOLUCCAS

In 1604, Maldonado embarked from Spain, from the port of Seville, together with the company of Juan de Esquivel with the aim of participating in the reconquest of Ternate, the so-called “Jornada de Terrenate“. Arriving in Mexico City, Maldonado received an “entretenimiento” from the viceroy of New Spain, the Marquis de Monteclaros. He arrived as an “entretenido” in the Philippines together with the company of Juan de Esquivel (the salary of “entratenido” was 20 pesos per month).21

THE CONQUIST OF TERNATE AND THE MOLUCCAS

In the capture of Ternate in 1606 Fernando Centeno Maldonado distinguished himself in the vanguard of the troops and was posted on sentry less than an arquebus shot from the enemy wall (i.e. from the fort of ‘Nuestra Señora‘), his work as a lookout was of great importance in the unfolding of the battle because it allowed the Spanish troops to respond effectively to the counter-moves of the Ternatese. He was one of the first to enter the conquered city. In his “Informaciones” regarding these facts, the certifications of Acuña, Gallinato, Vergara and others are reported.22

After the conquest of Ternate, on April 18, 1606, he was appointed ensign (the pay of ‘alférez‘ was 25 ducats of 11 reals per month) of the company of Francisco de Salçeda, in which he served for more than a year, until May 1, 1607. During this year of service he distinguished himself several times in the battles against the Dutch and actively participated in the fortification works of the various Spanish garrisons.

In May 1607, after 8 Dutch ships commanded by Cornelio de Matalief had arrived in Ternate, he made “dejacion de la bandera” (probably he abandoned his position as ‘alférez‘) serving in the company of Captain Juan Texo. In 1608, he participated as leader of the troops of a galley, under the command of Pedro de Heredia, in an attack on the Dutch fort of Malayo. Due to the Dutch reaction the Spanish were forced to retreat losing 13 soldiers as well as many wounded, of the 60 soldiers who took part in the battle. Also in 1608 having arrived another 10 Dutch galleons, he participated, still under the command of Heredia aboard a galley, in another expedition against the enemy, during which the village of “Bocanora” (Gamocanora) and the fortress of Jilolo were captured and burned.23

Still in 1608 Maldonado led several Spanish expeditions against the Dutch fort of Malayo, in one of these, on August 4, 1608, he was sent with 50 Spanish soldiers and 50 Indians to examine the enemy fortifications in Malayo and with the task of capturing some enemy in order to have fresh information on what the Dutch were plotting. He managed to plot an ambush, in the vicinity of Malayo (“a tiro de arcabuz”), against a small enemy boat carrying six Dutchmen, killing one and capturing another. He then had other clashes with the enemies where he captured the sangage of Toloco and two other Dutchmen and several Ternatese were killed.

On March 10, 1609, he was appointed by Juan de Esquivel, captain of infantry (the captain’s pay was 60 ducats and 11 reals a month) of the company that belonged to Captain Pedro Seuil de Guarga24, who had recently died. A few days after signing this promotion, the mestre de camp Juan de Equivel also died. The date of Esquivel’s death must be placed after March 10 and before March 20, 1609.25 Vergara’s statements also confirm the fact in which he affirms that due to Esquivel’s death, it was he Vergara who, having assumed the government, placed the company under the orders of Maldonado. The promotion was confirmed by charter dated October 13, 1609 by Don Juan de Silva.

Maldonado remained in Ternate for nine years, and for almost six years (from 10 March 1609 to 12 November 1614) he was captain of the Spanish infantry, here he participated with his company in several battles against the Dutch near the enemy fortress of Malayo, succeeding to capture several prisoners.

During the works for the construction of the fort of San Pedro y San Pablo in which Captain Zapata and Captain Gregorio de Vidaña participated together with some infantry troops, the ensign Alonsso de Ortega tells us, the Dutch with two or three boats began to bomb the fort under construction to prevent the Spanish from completing the work, they did this for about 5 or 6 days preventing the Spanish from being able to work on the fortifications. One night on the orders of the mestre de camp Lucas de Vergara, Maldonado was sent with his company with the aim of bringing artillery to the fort, which evidently did not have any, in order to be able to counter the blows of the Dutch.

Maldonado brilliantly managed with his company to rout the Dutch boats that had besieged the fort of San Pedro y San Pablo (“que esta çerca dela fuerça de Terrenate”) managing to bring reinforcements and artillery to the besieged fort, the artillery was transported by boat, while Maldonado and his troops passed by land. The witness who tells us about this fact is Alonsso de Ortega, he was ‘alférez‘ of the company of Vidaña and participated in the escort of the boat with the artillery, a boat that skirted the coast and arrived in the vicinity of the fort passing close to the enemy ships. With artillery at the disposal of the Spanish, the Dutch were forced to withdraw, allowing the Spanish to build the fort of San Pedro y San Pablo. The event is to be dated in 1609.

Having arrived a large Dutch fleet, Maldonado was then sent, by the governor of the Moluccas, Lucas de Vergara Gabiria, to Manila in search of relief, a task he carried out with great diligence, returning to Ternate, in February 1610, with an important and “muy copiosso socorro” together with the new governor of the Moluccas, Cristobal de Azcueta.

According to Azcueta’s testimony (“auiendo acordado el Señor D. Juan de Silva …….. tomar y fortificar al puesto de Toloco serca de Malayo”)26, in 1611, the governor of the Philippines D. Juan de Silva, decided to occupy and fortify the post of Toloco near Malayo (“serca de Malayo”), for this he ordered three companies to help fortify the place. At the head of the three companies was appointed Fernando Centeno Maldonado who with his company and together with those commanded by Andres Hinete and Pedro Çapata helped to fortify the post.

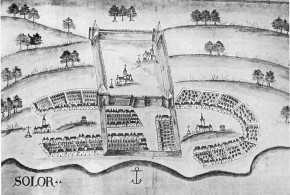

After the conquest of the stronghold of Jilolo (Gilolo) on the island of Halmahera, the governor of the Moluccas Cristobal de Azcueta, appointed him, on March 24, 1611, head of that garrison (“cauo superior dela fuerça de Jilolo e su distrito”), with orders to fortify it and keep it under Spanish control. Shortly after the conquest of Jilolo, the Dutch and Ternatese attacked the Spaniards, but thanks to Maldonado’s good conduct, every enemy attempt was rejected. At Jilolo, Maldonado built two fortresses (“hiço dos fuerças con mucho cuidado y trabajo”), one above, probably the old fort of Jilolo and a new fort below, located on the shore. This second fort was built on the orders of Azcueta, it was called “Fuerte de San Xpuoal”, and it was located “abajo en la marina en el agua caliente”, the fort was very strategically important for the preservation of Jilolo stronghold. Both forts were of “cal y canto” and were among the best forts the Spanish had in the Maluku Islands (“le pareze conforme a su gusto ser delas mejores que su Mag.d tiene en aquellas yslas” according to the declaration of the ensign Diego de Leon). Azcueta held Maldonado in good esteem, according to Juan Gutierrez Paramo. A month and a half after Juan de Silva’s departure for Manila, Azcueta visited the garrison of Jilolo where Maldonado was chief, Francisco de Romanico, who accompanied Azcueta, informs us of this.

For three years he governed Jilolo where thanks to his good conduct he brought many natives to the side of Spain, during his rule he had several clashes with the inhabitants of Sabugo, who he repeatedly defeated by destroying several enemy villages and capturing several boats. In one of these clashes a “caracoa” was attacked where 40 enemies were killed and captured, among the dead was also an uncle of the sultan of Ternate. He thwarted an attempt at treason by the inhabitants of Jilolo, who had made agreements with the Dutch and Ternatese to cede the stronghold and have the Spaniards killed. The rebellious inhabitants of Sabugo were forced to retreat to ‘Bocanora‘. With a document dated January 5, 1614, Geronimo de Silva ordered Maldonado to hand over command of Jilolo to Captain Pedro de Hermua and to return to Ternate with the same “parao” with which Hermua had arrived.

In a document dated January 18, 1614, Geronimo de Almança (“condador, factor juez oficial dela Real hacienda desta Ciudad del Rosario y fuerça de Terrenate”), informs us that Maldonado was leaving for Manila. In 1614 he was in fact recalled, by order of the governor of the Philippines, Juan de Silva, to Manila, to inform him of the state of the garrisons, being a person familiar with the needs that the Spanish forces of the Moluccas had. With a letter dated January 18, 1614, Geronimo de Silva orders Maldonado to embark on the Patacco ‘San Jhosep‘ for Manila. It seems that the date of his departure for Manila is to be placed between the end of January and March 1614 (Juan Gutierrez Paramo tells us “por principio del año de seis cientos catorze”).

Maldonado was married, 1614 in Manila,27 with doña Maria de Albarado Bracamonte, sister of the ‘licenziado‘ Don Juan de Albarado Bracamonte, fiscal of the Audiencia of the Philippines. Following these exploits, and on the occasion of his marriage, Maldonado received, from Don Juan de Silva, on August 2, 1614, an “encomienda” of half the tributes of the villages of Sagonay and Calompit (Hagonoy y Calumpit), which expenses represent a meager income of about 400 pesos a year. The other half of the encomienda was awarded to senior sergeant Esteban de Alcázar28, that on the same day he had married doña Isabela de Alvarado, sister of Maldonado’s wife. This encomienda, which had been of the captain and sergeant major Juan de Morones and then of his widow Ana de Monterey, after the death of both is confirmed to Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado in 1616.29

With a charter dated September 20, 1614, by the same governor of the Philippines, Maldonado was appointed sergeant major of the Ternate forces, in addition to this he was charged with commanding the fortress of Ternate in the absence of the governor Geronimo de Silva, who had to go to Tidore to calm the spirits of the King and the Prince. The orders for Geronimo de Silva were clear, he had to move to Tidore with as many soldiers as possible, while still leaving a good garrison in Ternate “en essas fuerzas de la Ciudad del Rrosario y fuerza de Sanjil y Donjil“. The aim was to preserve the island and in particular the loyalty of the King and his son the Prince of Tidore. Maldonado, with Juan de Silva’s charter of October 31, 1614, was also entrusted with the command of a company of arquebusiers, the company was that of Pedro de Hermua, who had been granted the license required to go to Manila.

At the end of 1614 we find him in Manila where he is preparing the new ‘socorro‘ for Ternate. The boats of the “socorro“, two caravels, a ‘patacco‘ and a galliot (Romanico speaks of a galliot and two caravels; Juan Moreno Criado and Diego de Leon say they were two caravels and a galley), entrusted to Maldonado were ready to depart, as per Juan de Silva’s charter of 31 October 1614, for the first days of November. But the departure was delayed, in fact the orders for Maldonado are dated January 23, 1615. In these orders it is indicated that the expedition was to stop in the province of Oton, and here it was to load rice and other foodstuffs, after a stop at the Caldera port to stock up on water, the expedition had to head directly towards Ternate. The expedition reached Ternate without wasting time or boats, despite the fact that the Dutch were on guard with 7 large ships.

On April 10, 1615, Geronimo de Silva, in the city of Ternate, in the presence of captains Don Fernando Beçerra and Francisco de Bera y Aragon, of officers and soldiers, solemnly appointed Fernando Centeno Maldonado governor of the city and fortresses of the island of Ternate. In this occasion were handed over to Maldonado “la ynfanteria banderas de su Mag.d, caxa Real, almazenes, artilleria, muniçiones y pertrechos della, y la demas desta ysla y la ygleçia parrochal y conuentos desta ciudad”. Furthermore, this card informs us that the Sultan of the island was always present in Ternate, as prisoner of the Spaniards. Geronimo de Silva returned to Tidore.

There is little information of the short period of government as sergeant major in Ternate, Pedro de Hermua, in his testimony informs us that shortly after taking possession of his office, Maldonado visited some Spanish fortresses bringing relief and the necessary to maintain the garrisons. By order of Geronimo de Silva, he was then at Jilolo, where Pedro de Hermua was still chief and who was given the orders to hand over his company to Maldonado and the license to go to Manila. Captain Francisco Vera remained in Jilolo as head of the garrison. However, Maldonado’s stay in Ternate was brief, in fact with a charter dated 15 May 1615,30 the governor of the Moluccas Geronimo de Silva ordered him to return to Manila aboard the two caravels he had brought in the past ‘socorro‘, the command of Ternate was handed over to another captain (Becerra ?). With the same boats with which Maldonado returned to Manila, it seems that Pedro de Hermua also embarked, while was certainly part of the escort guard, Diego de Leon.

Maldonado indeed returned to Manila where he brought back the old sultan of Ternate, who had remained after de Silva’s 1611 expedition to Ternate. The return to Manila of the old sultan must have taken place in the month of June or at the beginning of July 1615, because in the declaration of July 31, 1615 by the ensign Juan Moreno Criado it is clearly indicated that Maldonado was “un mes poco mas o menos que llegò a esta ciudad da las fuerzas de Terrenate” … “y trajo preso al Rey de Terrenate”. This sudden decision by de Silva to send the sultan of Ternate back to Manila, and Maldonado with him, leaves several suspects, perhaps that de Silva wanted to get rid of Maldonado’s presence?

In 1615, Maldonado had asked for 4,000 ducats of income from encomienda of Indians in the Philippines or in Mexico or Peru, he also asked for a habit of Santiago, Alcantara or Calatrava and for the position of maestre de campo of the Philippines or for a government position in New Spain or Peru. According to the opinion of the Audiencia, he could have been given the office of maestre de campo of the Philippines, or 3,000 encomienda tributes and one of the clothes he asked for.31

By means of a ‘Real Cedula‘ of June 9, 1617, he was recognized 1,000 pesos of income per year for two lives and was also entrusted with an encomienda of 2,000 pesos for two lives, the ‘Cedula‘ does not specify which encomienda, but it is defined as the first encomienda that will be free in the Philippines.32

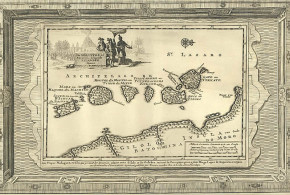

THE EXPEDITION TO MALACCA

In 1616 Maldonado took part in the expedition of Juan de Silva to Malacca embarking together with the governor de Silva on the captain ship. In the intentions of the governor of the Philippines Don Juan de Silva, this large joint expedition between the Spanish and Portuguese was to succeed in routing once and for all the Dutch forces present in the Indonesian islands. Even the Dutch were fearful of the success of such an expedition.33 In 1612, in order to make an agreement with the viceroy of Portuguese India, de Silva had sent the former governor of Ternate Cristobal de Azcueta to India but the entire expedition led by Azcueta disappeared in a shipwreck between Manila and Macao.

The governor of the Philippines did not lose heart and this time he entrusted the task of reaching Goa to two Jesuits, they were Father Pedro Gomes, rector of the company in Ternate and Father Juan de Ribera, head of the Manila college. The two Jesuits left at the end of 1614 (Ribera left on 21 November 1514 from the port of Cavite) in two different fleets for Goa, where they arrived without problems in 1615. The agreement that the two fathers reached with the viceroy led the Portuguese to contribute with 4 large galleons which were sent to Malacca. Father Pedro Gomez returned to Manila in July 1615 to warn the governor of the results of the expedition and to point out that the 4 galleons would soon leave for the Philippines. De Silva was preparing a large fleet. In order to procure artillery for this expedition, he weakened the defenses of the city of Manila with serious risks in the event of an attack on the city by the Dutch.

Not seeing the Portuguese galleons that had been promised to him arrive, he thought of going to meet them. Despite the negative opinion of many of his subordinates, he decided to leave in February 1616 for Malacca, instead of heading immediately towards the Moluccas where it seems that Gerónimo de Silva had already concluded agreements with the natives of the islands of Maquien and Motiel who, in case of arrival of this great expedition they would have rebelled against the Dutch and would have helped the Spanish.34

The governor was in ill health, it seems that the disease had already manifested itself before departure from Manila. There are testimonies of the poor health of the governor since the first expedition to the Moluccas in 1611. He had already several times sent petitions to the King to be replaced in his position and to be able to return to his homeland.

On February 9, 1616, however, the governor of the Philippines left Manila at the head of a large expedition consisting of 10 large galleons, 4 galleys, a ‘patacco‘ and other minor vessels. The galleons were the capitania “Salvadora” of 2000 tonnage, the almiranta “San Marcos” of 1700 tons, the two galleons “San Juan Bautista” and “Espiritu Santo” each of 1300 tons, and then smaller galleons “San Miguel” (800 tons), “San Felipe” (800 t.), “Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe” (700 t.), “Santiago” (700 t.), “San Andres” (500 t.), “San Lorenço” (400 t.). 5,000 men including soldiers and sailors were embarked on this fleet, of whom just under 2,000 were Spaniards, there was also an infantry unit of Japanese soldiers, finally there were about three hundred artillery pieces embarked on the ships. Six Jesuits also took part in the expedition.

The fleet was the largest army seen in the islands, Father Colin tells us, who marvels that “en tierra tan recien conquistada, y poblada de Españoles, y la mas remota, y distante de toda su monarchia, pudiesse llegar a quaxarse una tal maquina“. He headed for the Strait of Malacca, where he intended to join forces with a Portuguese army and together attack first the Dutch farm in Java and then the Dutch bases in the Moluccas.. But the Portuguese fleet sent by the Viceroy from Goa, had already been completely destroyed in the vicinity of Malacca, it was attacked by Dutch ships and the Portuguese to prevent the capture by the Dutch of the large galleons were forced to burn them.

The Spanish armada entered the Singapore Strait on February 25, 1616. From the Singapore Strait, de Silva sent with a “socorro” to Ternate Juan Gutierrez Paramo, again commissioned as sergeant major.35 Juan de la Umbria was probably also sent to Ternate together with Paramo.36 De Silva’s health worsened and on April 19, 1616, after eleven days of suffering, he died in the city of Malacca. The whole enterprise ended in a colossal fiasco, nothing was done against the Dutch and de Silva’s death in Malacca, which occurred shortly after his arrival, caused the inglorious end of this expedition.

The armada returned to Manila in early June 1616.37 Furthermore, due to fevers and diseases that struck the fleet during its stay in Malacca and in the Singapore Strait, most of the men of the fleet died, the ships returned to Manila “sin jente“. De Silva’s decision to go first through Malacca instead of going directly to the Moluccas is somewhat strange, also considering that the Portuguese galleons were according to the agreements to reach the Philippines to join the Spanish fleet. At the time of de Silva’s departure from Manila they must have arrived long ago if they had not been intercepted by the Dutch. Oddly enough, de Silva still wanted to try to join his forces with the Portuguese despite this time having a large and important naval force at his command and the Dutch position in the Moluccas being very precarious as several witnesses inform us, “el enemigo estua flaco en aquella saçon“. Vergara was certain that if the Spanish fleet went directly to the Moluccas without delay without passing through Malacca, most of the islands would have been conquered by the Spanish.38

THE PHILIPPINES

After the failure of the expedition Maldonado returned to Manila, where the audiencia appointed him governor of the people of war of the city of Manila, he took part in the battle of Playa Honda in 1617 under the commands of General Don Juan Ronquillo, embarking in the galley captain.

Under the rule of Geronimo de Silva in the Philippines, he was appointed general of the royal galleys. In 1620 he was sent by order of Fajardo de Tença to the Capul landing stage, to wait and escort the ships coming from New Spain. In 1621, he was promoted general of the ships going to New Spain, but the voyage was not made so he was reinstated in his previous position of general of the royal galleys, a position Maldonado still held in August 1623.39

In March 1621 a Real Cedula had been issued in Madrid in which license was granted to Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado residing in the Philippines to come to Spain for a period of four years. 40

In the Real Cedula of 1622 the king of Spain, in case of the death of the governor of the Philippines, “…en caso que muriesse el Gouernador dellas subsediessem en el cargo de capitanes fuistis uno de los nombrados…” Fernando Centeno Maldonado is also nominated.41

On August 15, 1623 with charter of Alonso Fajardo de Tença, in execution of the Real Cedula, 472 full tributes are ‘encomiendados‘, i.e. half of the encomienda of Mambusao on the island of Panay. Documents from 1623 attest that Fernando Centeno Maldonado had served in the Moluccas for about 9 years, 6 of which he had served in a company with which, as we have seen, he had participated in numerous episodes of the fighting between the Spanish and the Dutch in those islands. Also in 1623 Fernando Centeno Maldonado still appears “casado con Dona Maria de Alvarado Bracamonte”, sister of Don Juan de Alvarado Bracamonte, “fiscal de la Audiencia” of the Philippines and of Don Luis de Alvarado Bracamonte, who had served the king in the Philippines for many years.42

In 1625 Don Jerónimo de Silva filed a lawsuit against Generals Fernando Centeno Maldonado and Juan Bautista de Molina, commanders of the San Raimundo and San Ildefonso galleons for excesses. The fact is related to the so-called third naval battle of Playa Honda, a battle in which de Silva accused Fernando Centeno Maldonado and Juan Bautista de Molina, commanders of the San Raimundo and San Ildefonso galleons, of not having complied with the orders given by him. De Silva aboard the galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, the captain ship of the Spanish armada, on April 12, 1625 discovered a fleet of Dutch ships in front of Punta de Volinao (Bolínao). The Spanish pursued all day and into the next day the Dutch ships waiting to be joined by the main fleet to give battle to the enemies. On April 13, 1625, some Spanish ships arrived including the galleons San Ildefonso, commanded by General Juan Bautista de Molina, and San Raimundo, commanded by General Fernando Centeno Maldonado. Don Jerónimo de Silva had ordered to attack the enemies, but, according to him, due to the fact that the two commanders did not obey de Silva’s orders, the Spaniards missed a good opportunity to deal a heavy blow to the Dutch.43

Further information on Maldonado’s period of service in the Moluccas and in the Philippines can be obtained from a document dated 1632. It is a Memorial of General Fernando Centeno Maldonado in which Maldonado requests a ten-year extension of the license, which he had received in 1621 for 4 years, to return to Spain to pay off his parents’ inheritance. Maldonado says he has served the king of Spain for about 30 years and of these about 27 he has spent serving Spain in the Moluccas and the Philippines, in the last three years he had instead served as governor of Yucatan.44 The response to Maldonado’s request comes for the first time with Real Cedula in 1633, in this document the license is extended for two years.45 Then, the following year, in 1634, there is another Real Cedula in which an extension of another four years is granted to the license he had been given to come to Spain.46

THE YUCATAN

A few years later Maldonado is in Mexico. After arriving in Mexico from the Philippines in 1631, he was charged by the viceroy of New Spain with the government of Yucatán.47 The Viceroy, Rodrigo Pacheco y Osorio, III Marqués de Cerralbo, knowing his experience, sent him as governor to the province of Yucatán, in place of Don Juan de Vargas, who had been imprisoned in Mexico City.48

Fernando Centeno Maldonado was governor of Yucatán on two occasions: the first between November 1631 and August 1633, the second between June 1635 and March 1636.49

FIRST TERM OF GOVERNOR

Don Fernando took possession of his office as interim governor of Yucatán on October 28, 1631, when he arrived in Campeche.50 On November 10, the new governor reached the provincial capital, the city of Merida.51 He was appointed ad interim to succeed D. Juan de Vargas Machuca who had been imprisoned for serious abuses in the exercise of his office and in particular for appointing “jueces de grana” in the region who arbitrarily plundered the Mayan population.

By the time Fernando Centeno Maldonado took office, the region had suffered a prolonged series of calamities. The Indian villages were depopulated, the population had taken refuge in the forest in search of food and basic necessities. However, this situation could not be tolerated by the Spanish government, there was in fact the risk that the natives would return to their old practices of worship, and even worse, that they would free themselves from the control of the Spanish government and that of their own “encomenderos”. To resolve the issue Maldonado brought together the most prominent people of Merida in an assembly and in this assembly it was decided to persuade the natives without the use of force, but to persuade them with good manners. For this purpose, were chosen two Franciscan friars who knew the Mayan language well, the two were Pbro. D. Eugenio de Alcántara and Friar Lorenzo de Loayza. They were given the task of reaching the natives in the localities where they had taken refuge and persuading them to return to their villages. For this purpose, the Spaniards provided those who returned to their villages with food and sustenance. In their work the two friars were also accompanied by the new governor, who also used the mission to visit the villages and get to know the province where he was to govern. The mission lasted four months. In addition to food, the natives were also given “solares” and houses where they could live. The tactic was a great success, over 16,000 Indians settled along the coast alone (excluding from the count children and teenagers).52 In another document, Maldonado indicates that the Indians who fled from the villages and hid in the mountains numbered more than forty thousand.53

Fernando Centeno Maldonado, however, realized that some indigenous leaders tended to hide some indigenous people to be able to use them on their properties. To prevent this he decided to act harshly: as soon as he arrived in a village he had a gallows erected and he solemnly had a city crier proclaim the prohibition of this practice in the Mayan language under penalty of gallows. The result was that beyond that it was not necessary to do anything else, because none of the native chiefs risked to suffer such a sentence. The governor, to avoid further temptation, sent Spanish soldiers to burn the uninhabited farms that the natives had established in the forest.54

These facts are also narrated in another document by Maldonado dated November 1632 where the governor informs us of the state of the region where a large number of Indians had left the province and taken refuge in the mountains.55 In another document, also dated November 1632, Maldonado points out the importance of founding a garrison of 50 soldiers in the province to limit the numerous revolts and rebellions of the natives. This would also be useful to safeguard the safety of the religious who live in this province. In recent times, in fact, two friars and a chaplain had been killed as well as some soldiers who were trying to put down the frequent rebellions.56 The only ones who administered the Christian doctrine in the province were the Franciscans, according to Fernando Centeno Maldonado, governor of Yucatán, in a letter to the king dated November 1632. In the whole province there are 104 friars who maintain 35 convents.57

In July 1632 the governor moved to Campeche together with some troops to face the threat of the corsairs, but this threat did not materialize. In October 1632, Maldonado, governor of the province, wrote to the Viceroy informing him of the need to fortify the port of Campeche.58 But it seems that little was done, because the following year, in the month of August 1633, ten corsair ships with over 500 men on board attacked the city of Campeche, conquering it, after a short fight, and sacked it.59 The corsairs were commanded by Pie de Palo, i.e. the Dutchman Cornelis Jol60, and Diego El Mulatto.

In the days in which these events took place, in August 1633, the new governor of the province, Jerónimo de Quero, arrived.61 After the arrival of the new governor Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado retired to live in the city of Campeche with his family.62 Maldonado remained to live in Campeche until the news of the death of Governor de Quero on March 11, 1635. Having received the news of his death, he embarked for Goazalcoalcos (Coatzacoalcos) and from there reached Mexico City, where he requested the appointment of interim governor.63

SECOND TERM OF GOVERNOR

Maldonado’s request was accepted and on June 23, 163564 he arrived in Campeche taking over the government of the province. He appointed his lieutenant and assessor D. Cristobal de Aragon y Acedo. In one of his writings dated August 1635, Maldonado underlines the importance of building a fort for the defense of Campeche. This new fort was to be fitted with six bronze cannons which would have been of benefit to the defense of ships. Maldonado informs that the place he was considering for the erection of this fort was very good with easy procurement of building materials and with many Indians available for the fortification work. Maldonado considered that the fortification could have been built with about thirty thousand ducats.65

In his second mandate it seems that Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado was more interested in personal gain than in respecting the King’s orders. In fact, in August 1633 the King had ordered the abolition of the “jueces de grana, vinos y repartimientos“, favoring the natives, but as soon as he was in government he appointed his own judges and began his own speculation of agreements and contracts with the natives. This meant that the “Ayuntamiento y Alcades de Mérida” accused him before the “Consejo de Indias“. However, this move was not made with the aim of favoring the indigenous people, but rather only for fear of some that a new Maldonado government had disadvantaged them in their interests. In fact, after the end of his first period of government, it seems that many false friends of his powerful days had now abandoned him. The same, now that Maldonado was governor again, feared being penalized.66

Another mistake that Maldonado made in his second term was to meddle in religious affairs that were not within his direct competence. In fact he tried to meddle in the affairs of the Franciscans after the election of the provincial father by supporting the minority group of friars. This provoked a reaction and a complaint to the Viceroy of New Spain from the elected Provincial, Friar Bernabé Pobre. Knowing of the complaint, Maldonado met, on January 14, 1636, the Ayuntamiento of Mérida and sent a paper to the Viceroy signed by the members of the Ayuntamiento which defended the work of Maldonado. However, the deed came too late, in fact, the Viceroy, Lope Díez de Aux y Armendáriz, Marquis de Cadreita, dismissed him with an order signed on January 19, 1636.67 His place was taken by General D. Andrés Pérez Franco who took possession of the government of Yucatán on March 14, 1636 in Mérida. After this disappointment Fernando Centeno Maldonado immediately left with his family for Campeche from where he intended to embark for Veracruz. But Fernando Centeno Maldonado never arrived in Campeche, but he died about 50 kilometers away, in the town of Hecelchakán. He was buried in the convent of this town.68 According to a document dated 1637, Maldonado left his widowed wife and two little girls, who must have been 2 and 3 years old at the time of his death.69 Maldonado must have been widowed by his first wife, and during his stay in Mexico he must have remarried for the second time.

THE WIDOW OF MALDONADO: ISABEL DE CARABEO

The misadventures for the Maldonado family did not end, because the widow, Isabel de Carabeo, after her husband’s burial, embarked for Veracruz on the first available ship. But her boat was attacked by the corsair Diego El Mulato who captured the ship and all the passengers. Luckily for Isabel the privateer knew her and treated her well. In fact, Maldonado’s family, made up of the widow and two small girls, was released after a few days.

A document dated 1662, which contains a testimony made in August 1658, informs us that three daughters were born from the marriage between Fernando Centeno Maldonado and Isabel de Carabeo (y Silva). The eldest daughter (who, as we have seen, was called Teresa) is deceased while the names of the other two daughters are mentioned: Dona Maria (Senteno) and Dona Elena (de Silva y Guzman). From this information we can deduce that at the time of Fernando Centeno Maldonado’s death, his wife Isabel was expecting another child.70

Ferdinando Centeno Maldonado’s widow, Isabel de Carabeo sent in October 1637, a request for an encomienda for her daughter Teresa to be able to enjoy the encomienda she had inherited from her father in the Philippines despite the fact that the little girl resided in Mexico. In her request, Maldonado’s widow also asked that in the event of the death of her eldest daughter, the same rights as hers could be inherited by her second daughter. In the same document are the memorial of the services rendered by her husband and the official letter from Gabriel de Ocaña y Alarcón to Juan Pardo informing him of the mercy granted to Isabel de Carabeo, dated Madrid, December 22, 1637.71

In December 1637, the Council of the Indies grants Isabel de Carabeo (in February 1638 Juan Grau requests the correction of the error that occurred on behalf of the widow of Fernando Centeno Maldonado for having put in the document the incorrect name of Isabel de Carvajal in place of Isabel de Carabeo), widow of Fernando Centeno Maldonado that her eldest daughter, Teresa (Theresa), who is 4 years old, has the right to the fruits of the encomienda that her father had in the Philippines. That right was granted to her even though the little girl was residing in Mexico at the time on the condition that she keep a squire “y sirviendo per esta gracia con mill pesos en reales de plata dople pagados en la caxa real de la Ciudad de Mexico de la Nueva España”, and if he dies this right will pass to his sister who is 3 years of age. This is granted because a similar thing had already been done with the wife of Esteuan de Alcazar who also had an encomienda in the Philippines.72

In the archive of the Indies of Seville there are other documents dealing with the granting of the encomienda to the daughter of Fernando Centeno Maldonado. The first document is dated February 27, 1638 and is the “Real Cédula“, i.e. the royal decree which grants Teresa, the eldest daughter of Fernando Centeno Maldonado, of the “encomienda” of her late father, even if she does not reside in the Philippines, provided that put a squire and that one of his sisters could succeed her in case of death.73 The order to debit Isabel de Carabeo for the encomienda also dates from the same date. This is the Royal Decree for officials of the Royal Treasury of Mexico, to collect from Isabel de Carabeo, widow of Fernando Centeno Maldonado, a certain sum of money for the mercy that has been done to a daughter of hers who can enjoy the encomienda of the father.74

The last document is dated May 6, 1638 and is the Royal Decree (“Real Cédula”) to the president and members (“idodores”) of the Audiencia of Mexico, so that the 1,000 pesos owed by Isabel de Carabeo, widow of Fernando Centeno Maldonado, for the mercy that has been shown to his daughter Teresa so that she may enjoy the encomienda of her father in the Philippines which has been entrusted to her, even though she resides outside those islands, such money be withdrawn from whoever has to pay it, and be sent to Spain.75

Subsequently, Isabel de Carabeo married in second marriage to Diego Orejón Osorio, a document of 1650 informs us of this, a “Real Cedula“, in which we also learn that Isabel has complied with the obligation to pay the 1,000 pesos for the dispensation granted to his daughter Teresa, so that she can enjoy the encomienda she has in the Philippines, placing a squire to serve her.76

In the Archivo Histórico Nacional there is another document “Consultas y pareceres dados a S.M. en asuntos de gobierno de Indias, Vol. I” where there is a reference to Isabel de Carabeo. We read at number 741: “D.a Ysabel Carabeo 14 Diz.re (1657) pide 2000 Duc.os de Encomienda en consideracion de los servicios de sus dos maridos, y en conformidad de la ordenanza, se manda traza informe por el Virrey, y Audiencia, y per donde conte los servicios”.77

A last document shows the date of February 1662, it is a 76-page document where the merits of Fernando Centeno Maldonado and Diego Orejon Osorio, the two husbands of Isabel de Carabeo, are reported. In the document it is understood that Isabel is widowed again “…Don Fernando Zenteno y Don Diego de Orejon Osorio maridos que fueron de Doña Isabel de Carabeo vidua…”. Isabel required 2,000 ducats a year for the encomienda enjoyed by Doña Josepha Bazan in New Spain. According to royal officials, however, the figure of 1000 pesos “per su vida” per year seems quite “en la finca mencionada“.78

Isabel de Carabeo’s second husband, Diego Orejón Osorio, was awarded the dress of Knight of the Order of Santiago and held numerous military posts and political and justice offices during his life. He came to Mexico from the kingdom of Castile. He was a Spanish infantry captain in the garrison of the Nueva Ciudad de la Veracruz. He was ‘Alcalde mayor de la Villa Alta de San Idephonso‘. He was ‘Regidor‘ of Mexico City; ‘Alcalde Mayor de las Minas de Pachuca‘; ‘Alcalde Mayor y teniente de capitanos de la Provincia de Xicayan‘; ‘Alcalde‘ ordinary and ‘corregidor‘ of Mexico City; and finally ‘Alcalde mayor y teniente de capitanos de la Cidad de la Puebla de los Angeles‘ where he died in the exercise of his office.79

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica: Ministerios Apostolicos De Los Obreros De La Compañia de Iesvs,” vol. III

Correspondencia de Don Gerónimo de Silva” in “Coleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de España” Vol. 52, 1868

Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

Monumenta historica Societatis Iesu. Vol. 126: Documenta Malucensia III (1606-1682), 1984

Juan Francisco Molinas Solis “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOMO II, 1910

DOCUMENTS

Informaciones: Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1615

Signatura: FILIPINAS,60,N.18

Confirmación de encomienda de Hagonoy, etc

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1616-10-14

Signatura: FILIPINAS,47,N.4

Confirmación de encomienda a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1616-11-02

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,450,L.A4,F.227-227V

Asociado Consulta sobre merced a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1617-02-18

Signatura: FILIPINAS,1,N.175

Aumento de encomienda a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1617-06-09

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,450,L.A5,F.26-27

Carta del Cabildo secular de Manila y franciscanos recomendando a Alvarado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1619-08-06

Signatura: FILIPINAS,20,R.13,N.91

Carta del Cabildo secular de Manila sobre Alvarado Bracamonte

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1619-08-06

Signatura: FILIPINAS,27,N.113

Respuesta a Fajardo de Tenza sobre varios asuntos

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1620-12-13

Signatura: FILIPINAS,329,L.2,F.379R-386V

Petición de Fernando Centeno de licencia para venir a España

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1621-03-06

Signatura: FILIPINAS,38,N.64

Licencia para venir a España a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1621-03-29

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,450,L.A6,F.157V-158

MERITOS: Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1623-08-15

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,111,N.43

Carta del Cabildo secular de Manila pidiendo más agustinos

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1624-08-10

Signatura: FILIPINAS,80,N.99

Carta de Marcos Zapata sobre J. Legazpi, holandeses

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1625-07-30

Signatura: FILIPINAS,20,R.19,N.129

Carta de Jerónimo de Silva sobre asuntos de gobierno

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1625-08-04

Signatura: FILIPINAS,7,R.6,N.84

Confirmación de encomienda de Mambusao

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1626-07-02

Signatura: FILIPINAS,48,N.11

Confirmación de encomienda a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1626-08-01

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,451,L.A9,F.233-234

Orden a oficiales de Filipinas de cobrar a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1626-09-10

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,451,L.A9,F.262-262V

Petición del dominico Mateo de la Villa de limosna de vino y aceite

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1627-03-06

Signatura: FILIPINAS,80,N.120

Petición de Francisco de Rebolledo de encomienda de su mujer

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1631-08-11

Signatura: FILIPINAS,40,N.27

CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1631-12-02

Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.1

Petición de Fernando Centeno Maldonado de prórroga de licencia

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-07-23

Signatura: FILIPINAS,40,N.33

Carta del virrey Rodrigo Pacheco Osorio, marqués de Cerralbo.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-10-07

Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.9

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-11-08

Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.50

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-11-08

Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.52

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-11-08

Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.53

CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-11-08

Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.2

CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1632-11-08

Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.3

Prórroga de licencia a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1633-01-30

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,452,L.A15,F.86-88

Real Cédula

Real Cédula a Baltasar Sanli Casanova, confirmándole los indios que Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador interino de Yucatán, le encomendó.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1633-08-01

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,453,L.A16,F.12-13V

Prórroga de licencia a Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1634-06-07

Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.1,F.48R-50V

CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1635-08-12

Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.4

CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES

Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1635-08-12

Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.5

Real Cédula

Real Cédula a Martín de Vargas confirmándole los 300 pesos de minas, 150 fanegas de mais y 300 aves que D. Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador interino de Yucatán le situó como ayuda de costa por dos vidas

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1637-06-20

Signatura: INDIFERENTE,454,L.A20,F.140-142V

Petición de Isabel de Carvajal de encomienda para su hija

Memorial de Isabel de Carvajal (sic por Carabeo), viuda del general Fernando Centeno Maldonado, dando cuenta de los servicios prestados por su marido, y suplicando que la hija de ambos, Teresa, pueda gozar de la encomienda que heredó de su padre en Filipinas a pesar de residir en México, que dicha encomienda pueda heredarla su segunda hija en caso de fallecer la mayor, y que la composición se haga atendiendo a los méritos de su difunto marido.

Acompaña:

– Oficio de Gabriel de Ocaña y Alarcón a Juan Pardo avisándole de la merced concedida a Isabel de Carabeo. Madrid, 22 de diciembre de 1637.

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1637-10-02

Signatura: FILIPINAS,41,N.39

Consulta sobre merced a Isabel de Carabeo

Consulta del Consejo de Indias proponiendo que se haga merced a Isabel de Carvajal (sic), viuda de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, de que su hija Teresa pueda gozar de los frutos de la encomienda de su padre en Filipinas residiendo en Mexico a condición de que ponga escudero y sirva con 1000 pesos, y si muriese la goce su hermana.

R.: Acepta la propuesta.

Cat. 16522

– Memorial de Juan Grau pidiendo que se subsane el error que ha habido en el nombre de la viuda de Fernando Centeno Maldonado por haberse puesto en el memorial Isabel de Carvaja en lugar de Isabel de Carabeo. 26 de febrero de 1638.

Cat. 16605

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1637-12-01

Signatura: FILIPINAS,2,N.6

Concesión sobre la encomienda de Fernando Centeno Maldonado

Real Cédula concediendo a Teresa, hija mayor de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, que pueda gozar la encomienda de su difunto padre, aunque no resida en Filipinas, siempre que ponga un escudero en ella, y que una hermana suya pueda sucederla a ella en caso de muerte. Hizo la petición su madre Isabel de Carabeo. (Cat. 16607)

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1638-02-27

Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.2,F.37V-41R

Orden de cobrar a Isabel de Carabeo por encomienda

Real Cédula a los oficiales de la real Hacienda de México, para que cobren a Isabel de Carabeo, viuda de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, cierta cantidad de dinero por la merced que se ha hecho a una hija suya de que pueda gozar la encomienda de su padre. (Cat. 16608)

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1638-02-27

Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.2,F.41R-42R

Orden sobre cobro por una merced de encomienda

Real Cédula al presidente y oidores de la Audiencia de México, para que los 1.000 pesos con que sirve Isabel de Carabeo, viuda de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, por la merced que se le ha hecho a su hija Teresa de que pueda gozar la encomienda que su padre tenía en Filipinas, aún estando fuera de aquellas islas, se cobren de las personas que los deban pagar, y que siendo parte legítima sus curadores se cobren de ellos y se envíen a España. (Cat. 16642)

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1638-05-06

Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.2,F.52V-53R

Cumplimiento de la obligación contraida por Isabel Carabeo

Real Cédula a declarando haber cumplido Isabel Carabeo, mujer de Diego Orejón Osorio, los mil pesos que quedó obligada a pagar por la dispensa que se concedió a su hija Teresa, para que pueda gozar la encomienda que tiene en Filipinas, poniendo escudero que la sirva.

(Cat. 81920)

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1650-03-11

Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.3,F.305V-306V

Consultas y pareceres dados a S.M. en asuntos de gobierno de Indias , Vol. I

741: “D.a Ysabel Carabeo 14 Diz.re (1657) pide 20_ Duc.os de Encomienda en consideracion de los servicios de sus dos maridos, y en conformidad de la ordenanza, se manda traza informe por el Virrey, y Audiencia, y per donde conte los servicios”.

Archivo: Archivo Histórico Nacional

Fechas: 1586 / 1678

Signatura: CODICES,L.752

Fernando Centeno y Diego Orejon Osorio

Archivo: Archivo General de Indias

Fechas: 1662-02-11

Signatura: MEXICO,244,N.25

NOTES:

1 AGI: “Petición de Isabel de Carvajal de encomienda para su hija” Signatura: FILIPINAS,41,N.39 Fecha creación: 1637-10-02 Código de referencia ES.41091.AGI/25//FILIPINAS,41,N.39. Vedi anche: AGI: “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán”. CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES. Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.5Fecha creación: 1635-08-12 , Mérida de Yucatán. Código de referencia: ES.41091.AGI/25//MEXICO,360,R.1,N.5. See also: AGI: “Informaciones: Fernando Centeno Maldonado”. Signatura: FILIPINAS,60,N.18. Fecha formación: 1615. Código de referencia: ES.41091.AGI/25//FILIPINAS,60,N.18

2 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

3 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

4 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

5 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

6 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

7 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

8 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

9 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

10 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

11 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

12 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

13 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

14 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

15 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

16 Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

17 See note 1 of the translator H.-D. de Grammont in: Jeronimo Conestaggio “Relation des préparatifs faits pour surprendre Alger” 1882

18 See: Juan de Cardona y Requesens in “Real Academia de la Historia” http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/29085/juan-de-cardona-y-requesens

19 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18

20 Bernardo José García “La pax hispánica: política exterior del Duque de Lerma” 1996, Leida, pag. 42-45 where a document is indicated: “Consulta del consejo de estado sobre lo que escribio Juan de Cardona en carta de 10 de septiembre de 1602 sobre las empresas de Argel, Bugia, y hazer alguna correria con la Armada” (Valladolid 17 septiembre 1602: AGS.e. Expediciones a Levante leg. 1948. f. 94)

21 The term “entretenido”, which is no longer used today, was widely used in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the civil and administrative sense it meant a person who had merits to obtain a position. In the military it had a complex meaning: they were usually experienced soldiers, old captains, and reformed sergeants, who had fought many wars, but who could no longer serve as ordinary soldiers. These soldiers were to follow their general or commander and were a sort of guardhouse for the general.

22AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18

23 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18 dove c’è anche la testimonianza di Pedro de Heredia su alcuni di questi fatti.

24In my opinion Vergara’s wife was the daughter of this captain you see: Monumenta historica Societatis Iesu. Vol. 126: Documenta Malucensia III (1606-1682) Doc. 38: “Masonio a Acquaviva, Ternate, 20 marzo 1609” pp. 151-152

25Monumenta historica Societatis Iesu. Vol. 126: Documenta Malucensia III (1606-1682) Doc. 38: “Masonio a Acquaviva, Ternate, 20 marzo 1609” pp. 151-152

26 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18, foglio C36

27 Correspondencia de Don Gerónimo de Silva” in “Coleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de España” Vol. 52, 1868, p. 255

28 On Esteban de Alcázar see: Marco Ramerini ”Esteban de Alcázar, un soldato al servizio del re di Spagna in Europa, alle Filippine e alle Molucche” 2021, https://www.colonialvoyage.com/esteban-de-alcazar-un-soldato-al-servizio-del-re-di-spagna-in-europa-alle-filippine-e-alle-molucche/

29AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Hagonoy, etc” 1616-10-14 FILIPINAS,47,N.4

30 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18, fogli a56-a57

31 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18, Bloque 4, foglio 5 (240). AGI: “Asociado Consulta sobre merced a Fernando Centeno Maldonado” 1617-02-18 Signatura: FILIPINAS,1,N.175

32AGI: “Aumento de encomienda a Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1617-06-09. Signatura: INDIFERENTE,450,L.A5,F.26-27

33 “Generale Missiven” vol. I pp. 37-38

34 Correspondencia de Don Gerónimo de Silva” in “Coleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de España” Vol. 52, 1868, pp. 284-285

35 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Filipinas. Juan Gutierrez Paramo. 10-03-1625”, Filipinas,48,N.1

36 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Marinduque, etc. Juan de la Umbria. 02-10-1623”, Filipinas,47,N.60

37 For more information on this expedition see the extensive report given in: Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 581-646

38 AGI: “Carta de Lucas de Vergara Gaviria al Rey defensa Maluco. Terrenate, 31 maggio 1619” Patronato, 47, R. 37

39AGI: “MERITOS: Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1623-08-15 Signatura: INDIFERENTE,111,N.43

40AGI: “Licencia para venir a España a Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1621-03-29 Signatura: INDIFERENTE,450,L.A6,F.157V-158

41 AGI: FERNANDO CENTENO Y DIEGO OREJON OSORIO. Archivo: Archivo General de Indias. Fechas: 1662-02-11. Signatura: MEXICO,244,N.25. Fogli: Bloque 2, Recto 10

42AGI: “MERITOS: Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1623-08-15 Signatura: INDIFERENTE,111,N.43

43AGI: “Carta de Jerónimo de Silva sobre asuntos de gobierno” Fechas: 1625-08-04 FILIPINAS,7,R.6,N.84

44AGI: “Petición de Fernando Centeno Maldonado de prórroga de licencia” Fechas: 1632-07-23 Signatura: FILIPINAS,40,N.33

45AGI: “Prórroga de licencia a Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1633-01-30 Signatura: INDIFERENTE,452,L.A15,F.86-88

46AGI: “Prórroga de licencia a Fernando Centeno Maldonado” Fechas: 1634-06-07 Signatura: FILIPINAS,347,L.1,F.48R-50V

47 AGI: FERNANDO CENTENO Y DIEGO OREJON OSORIO. Archivo: Archivo General de Indias. Fechas: 1662-02-11. Signatura: MEXICO,244,N.25. Fogli: Bloque 2, Verso 12. AGI: CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1635-08-12 Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.5

48AGI: CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1631-12-02 Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.1

49 Sergio Quezada, Tsubasa Okoshi Harada “Papeles de los Xiu de Yaxá, Yucatán” Mexico 2001: “Mandamiento de don Fernando Centeno Maldonado al cabildo de Yaxá (Oxkutzcab a 19 de marzo de 1632)” nota n°10 di pag. 71

50 AGI: FERNANDO CENTENO Y DIEGO OREJON OSORIO. Archivo: Archivo General de Indias. Fechas: 1662-02-11. Signatura: MEXICO,244,N.25. Fogli: Bloque 2 Verso 10

51 In this document there is the appointment as governor of Yucatan: AGI: FERNANDO CENTENO Y DIEGO OREJON OSORIO. Archivo: Archivo General de Indias. Fechas: 1662-02-11. Signatura: MEXICO,244,N.25. Fogli: Bloque 2 Recto 9, Verso 9

52 Juan Francisco Molinas Solis “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOMO II, 1910, pag. 92-95

53AGI: CARTAS DE GOBERNADORES “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, Gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1635-08-12 Signatura: MEXICO,360,R.1,N.5

54 Juan Francisco Molinas Solis “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOMO II, 1910, pag. 95-96

55AGI: “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1632-11-08 Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.50

56AGI: “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1632-11-08 Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.52

57AGI: “Carta de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, gobernador de Yucatán” Fechas: 1632-11-08 Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.53

58AGI: “Carta del virrey Rodrigo Pacheco Osorio, marqués de Cerralbo” Fechas: 1632-10-07 Signatura: MEXICO,31,N.9. El Gobernador de Campeche Don Fernando Centeno Maldonado al Virrey, sobre la fortificación de aquellos puertos. Campeche, 7-X-1632.

59 In the “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOME II, 1910, p. 103-105 also reports the account of a letter sent to the King by Fernando Centeno Maldonado, on September 19, 1633, shortly after leaving the office of governor to Jerónimo de Quero. The letter also mentions the conquest of Campeche by the corsairs, but Centeno minimizes the damage and looting done to the city by the pirates “sin haber hecho daño ninguno en las casas ni iglesias“.

60 Cornelis Jol was a Dutch privateer and admiral of the Dutch West India Company. Jol participated in numerous battles against the Spanish. In addition to the sack of Campeche, his most famous feat was the 1641 expedition to Africa which led to the conquest of the city of Luanda in Angola and the island of São Tomé, in the Gulf of Guinea. While in São Tomé, he was stricken with malaria and died on October 31, 1641.

61 Juan Francisco Molinas Solis “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOMO II, 1910, pag. 99-103

62 Juan Francisco Molinas Solis “Historia de Yucatán durante la dominacion Española”. TOMO II, 1910, pag. 103