Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Geoffrey A. P. Groesbeck

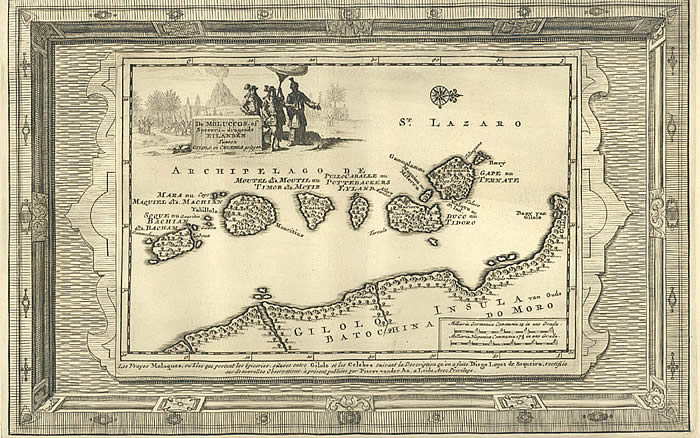

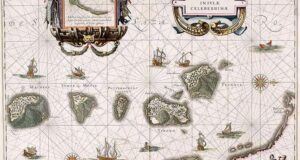

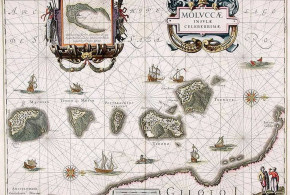

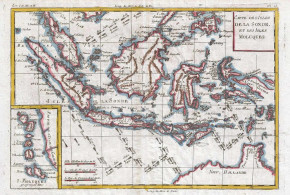

The islands formerly known as the Moluccas – the Spice Islands – are five islands of volcanic origin (Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian, and Bacan). They are found off of the west coast of the island of Halmahera, in the Indonesian archipelago.

These islands were the only ones in the world where, at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese (c. 1510), cloves grew wild. Clove is an aromatic spice of the family Myrtaceae, whose botanical name is Caryophyllus Aromaticus (in full, Eugenia Caryophyllata, Syzygium Aromaticum).

This singular condition made the Moluccas islands famous since the ancient times. Clove was one of the most important trading commodities. It was traded in the Asian markets (i.e., Arabic-speaking countries, and China and India) and also the European ones. Its oil was used for the treatment of food as well as like essence to perfume the breath, and as an anesthetic for toothache.

The Moluccas had this key, lucrative commodity, but had to import most of their foodstuffs from other islands: sago and rice, for example, came from Halmahera, Ambon and Bacan. Cloves were exchanged for clothing, silk, porcelain, gold, silver, knives, glass, and other items.

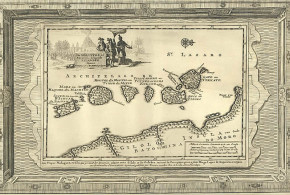

All the Moluccas are dominated by high volcanoes, some of which are still active. Beyond the five main islands, there are also three smaller volcanic ones: Hiri to north of Ternate, Maitara between Ternate and Tidore, and Mare between Tidore and Moti.

Because of the continuous trade contacts between the Moluccas and Muslim merchants from Arabia and elsewhere in Asia, Islam made its entry in the islands around 1430-1460, with the conversion of various local kings. With the subsequent arrival of Christianity with the Portuguese, these two religions represented an important, “elitist” element, although the majority of the population still remained animist.

In 1512, when the Portuguese first arrived, two main kingdoms controlled the Moluccas: the Sultanate of Ternate, and the Kingdom of Tidore. Ternate one controlled, in addition to the island by the same name, half of the island of Moti; the northern side of the island of Halmahera (called by the Portuguese Moro); the island of Ambon; the east part of Ceram; and the northeast area of Sulawesi.

Tidore controlled, in addition to Tidore itself, the other half of the island of Moti; the island of Makian; the greater part of the island of Halmahera; and the western side of New Guinea. Control on these islands was exercised directly or through vassalage.

Two other smaller states also existed: Bacan and Jailolo. Bacan, whose main village was on the island of Kasiruta, extended its influence over the archipelago of Bacan and to the northern side of Ceram. Bacan was a great producer of sago, the basic food of the sparsely populated islands.

Jailolo in the past had been the more important of the two entities, but by the 1500s it was in decline and controlled only the northwestern side of Halmahera. Jailolo essentially was annexed by Ternate and the Portuguese in 1551.

In 1522, the sultan of Ternate make an alliance with the Portuguese, asking for and obtaining the construction of a Portuguese fortress on the island. The first stone of the fortress was laid on the feast day of Saint John the Baptiste, on 24 June 1522. Thus, the fort was called “São João Baptista de Ternate”. The alliance with the Portuguese tipped the balance in favor of Ternate in its struggles with Tidore. As a result, the king of Tidore asked in turn for the help of the Spaniards when Magellan’s expedition stopped at Tidore.

As is well known, starting with the Magellan expedition of 1521, the Spaniards tried several times to gain control of the “Spice Islands” to thwart the Portuguese, with whom they often nearly came to blows. The Spaniards established alliances with the sultans of Tidore and Jailolo, and Spanish troops were present in the islands during the years 1527-1534 and again between 1544-1545. However, the failure to discover a return passage through the Pacific prevented the Spanish from competing with the Portuguese as a naval power. Earlier, in 1529, in an attempt to defuse the situation, an agreement was reached between Spain and Portugal, the Treaty of Saragozza. Under the terms of this treaty, the king of Spain had at least nominally abandoned the right for a Spanish presence on the islands in exchange for a sum of money.

The first period of Spanish interest in the Moluccas was characterized by fights against the Portuguese for the control of the islands. It began with the arrival of the Magellan expedition, and ended in 1545 with the surrender to the Portuguese by Villalobos’ army. Between these two expeditions, the Spaniards had sent other fleets, including those of Loaisa (1527) and Saavedra (1528), in addition to the unlucky expedition of Grijalva (1538). The expedition of Villalobos was launched after the Treaty of Saragozza; thus it was directed to seek commerce with unspecified islands, in other words, those not occupied by Portugal. The center of activity for the Spaniards remained for the whole period the island of Tidore.

This first period of interest for the Spaniards in the Moluccas, covering the years 1521-1606, can be divided into two distinct parts: the first part was that above, characterized by fights against the Portuguese for control of the islands, beginning with the arrival of Magellan’s expedition in 1521 and ending in 1545 with the surrender to the Portuguese of the men of Villalobos.

The second part of this first period took place during the union between the crowns of Spain and Portugal. At this time, Spanish expeditions departed from Manila in the Philippines and were organized with the aim of helping Portuguese troops defeat their Ternate enemies, who were rebelling against Portuguese control, and who had managed to expel them from the island. The main objective of these expeditions was the “reconquista” of the Portuguese fortress of Ternate. None of six successive Spanish attempts reached this objective, however.

These attempts began in 1582 with the expedition of Francisco Dueñas. This first expedition was only an information-gathering exercise, designed to learn more about the military situation on the islands. Francisco Dueñas remained in the Moluccas for approximately two months between March and April of 1582. The next expedition was that commanded by Juan Ronquillo, between 1582 and 1583, in which the Spaniards collaborated with the Portuguese in some punitive expeditions. In 1584, Pedro Sarmiento went, and then in 1585 Juan de Morón as well. Neither of these two expeditions had the hoped-for result: the fortress of Ternate was attacked, but without result. A larger and better assembled army left Manila in 1593 under the command of the governor of the Philippines, Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas. A rebellion and the murder of Dasmariñas before reaching the Moluccas cancelled the operation. The final Spanish expedition of this period was that sent from Manila to aid the fleet of the Portuguese admiral André Furtado de Mendonça. The Spanish assistance was commanded by Juan Juárez Gallinato, and left Manila at the end of 1602. A combined Spanish-Portuguese attack against the fortress of Ternate yielded no success.

What was instead successful was the attack by the Dutch on the fortress of Tidore in 1605. It was conquered on 19 May 1605. But without a sufficient number of men to garrison the conquered fort, the Dutch commander, vice admiral Cornelis Bastiaensz, was limited to leaving just a few men stationed at a small trading post. A Spanish response to the sudden Dutch presence was not late in arriving. In 1606, an expedition led by the governor of the Philippines, Pedro de Acuña, reestablished Iberian control on the Moluccas.

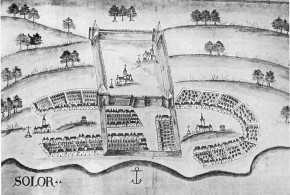

After his rapid victory, Acuña deported to Manila the sultan of Ternate, Said Barakat, with his son the prince, and all his dignitaries, in total about thirty persons. The Spanish remained on Ternate for 57 years, from 1606 until 1663 (although on the island of Siau, a very small Spanish garrison remained from 1671 to 1677). The Spanish also occupied a few smaller spice islands as well.

This period was characterized by continuous fighting against the Dutch, who nearly always had the upper hand at sea and better arms as well as more soldiers and ships. For most of the period the Spaniards had a faithful ally in the sultan of Tidore, while the Dutch had the same in that of Ternate.

After the conquest of Ternate in 1606, the Spaniards were nominally masters of the Spice Islands. However, they did not succeed overall, in contrast to the Dutch, who returned again and formed an alliance with the rebels on Ternate. In fact, the Spanish presence was mainly a military one thanks to the intransigent hostility of the Ternate rebels and the tenacious Dutch, who were more battle-trained in any case.

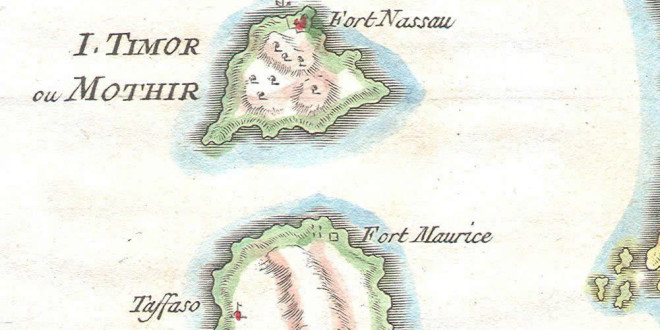

Starting from the year 1607, the Dutch extended their control over the more profitable and desirable part of the Moluccas. In 1607 they constructed a fort on the same island of Ternate just a few kilometers from the Spanish city. It was first known as Fort Malayo and later Fort Orange (Benteng Orange, in the city of Ternate). On the same island in October 1609, the Dutch built a fort at Tacome (Fort Willemstadt). The fort of Tacome was situated in the northern side of the island, in an area rich of cloves. A third fort also was constructed, in 1612, at Tolucco (Fort Hollandia). The main Dutch base in the Moluccas remained, however, Fort Malayo. In a few years, practically the greater part of the island of Ternate had been lost to Spanish control. Great aid was rendered to the Dutch from their natural allies on Ternate. In the same years when these forts on Ternate were built, Dutch control was extended also to the other islands of the archipelago. From 1608, the island of Makian also was occupied by the Dutch, who constructed three fortresses along the coasts of the island. Makian was the richest island in the area, and very much desired by the Dutch, who aimed to control its commerce in spices. Another fortress, Fort Nassau, was built in 1609 on the island of Moti (Motir), situated between Tidore and Maquiem (Machian). This island also was rich in cloves. Also in 1609, the Spanish fort of Bachan was captured by the Dutch commander, Vice Admiral Simon Jansz Hoen.

After 1606, and between 1607 and 1610, the Dutch with their native allies succeeded in putting the Spanish on the defensive and took control of the greater part of the islands. Under Spanish control remained only the southern side of the island of Ternate (with its main town of “Nuestra Señora del Rosario”); the entire island of Tidore; and some ports on the islands of Halmahera and Morotai. The Spanish garrisons had their headquarters in the islands of Ternate and Tidore. It is often difficult to understand by the documents where they were situated. The Spanish “presidios”, were sometimes called by different names, causing not a little difficulty in understanding which was which.

In addition to several fortified places on Ternate and Tidore, the Spanish from time to time sporadically maintained garrisons also on the peripheral islands of Halmahera, Morotai and Sulawesi. These were strategic locations for maintaining garrisons. The islands were sources of sago and other indispensable food for the maintenance of the garrisons and the population of the islands of Ternate and Tidore, two islands where difficult terrain and constant state of war did not allow the cultivation of such products. The Spanish garrisons depended on restocking of their food, clothing and ammunition supplies almost exclusively from the so-called fleet of “soccorro” that was sent every year from the Philippines. If one of these fleets was late, or worse still, was captured by the Dutch or shipwrecked in bad weather, there ensued enormous want on the part of both the Spanish soldiers of the garrisons and the population of the city of Ternate.

In spite of these deprivations and the high human and material cost, the Spanish maintained garrisons in Ternate, Tidore and other islands until 1663, when the governor of the Philippines, Manrique de Lara, decreed the dismantling and abandonment of all the garrisons of the Moluccas.

The Spanish town of Ternate: Ciudad del Rosario.

Extract from my studies: “The Spanish presence in the Moluccas, 1606-1663/1671-1677” and “Le fortezze Spagnole nell’Isola di Tidore, 1521-1663” (“The Spanish fortresses in Tidore Island 1521-1663, Moluccas, Indonesia“).

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

– Various Authors “Correspondencia de D. Jeronimo de Silva con Felipe III, D. Juan de Silva, el Rey de Tidore y otros personajes, desde abril 1612 hasta febrero de 1617, sobre el estado de las islas Molucas” In: “Coleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de Espana” vol. n° 52, pp. 5-439, 1868. Madrid.

– Argensola, Bartolomé Leonardo “Conquista de las islas Malucas” 372 pp. Ediciones Polifemo, 1992 (1609), Madrid, Spain. English edition: “The discovery and conquest of the Molucco and Philippine Islands” 260 pp. ills. 1708, London, UK. French edition: “Histoire de la conquete des isles Moloques par les espagnols, par les portugais, et par les hollandois. Amsterdam 1706” Sabin, 1947

– Belen Banas Llanos, Maria “Las islas de las especias. Fuentes etnohistoricas sobre las Molucas XIV-XX” 160 pp. Universidad de Extremadura, 2000, Caceres, Spain.

– Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James A. “The Philippine Islands 1493 – 1898” CD-Rom BPI Foundation Inc., 2001, Manila, Philippines.

– Colin, F. “Labor Evangelica” 3 vols. 1900-1903, Barcelona. Vol. I pp. xix+239+636 Vol. II pp. 725 Vol. III pp. 831

– Noguera, P. H. “Guia de fuentes manuscritas para la historia de Filipinas conservadas en Espana” Fundacion Historica Tavera, 1998, Madrid

– Pastells, P. “Historia General de Filipinas” Tomo V, VI, VII Barcelona, Spagna.

– Prieto Lucena, A. M. “Filipinas durante el gobierno de Manrique de Lara, 1653-1663” xiv+163 pp. Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla, 1984, Sevilla, Spagna.

– Ramerini, Marco “Le Fortezze Spagnole nell’Isola di Tidore 1521-1663” Firenze, 2008

– Van der Wall, V. I. “De Nederlandsche oudheden in de Molukken” xx, 313 pp. with 3 folding maps and 155 illustrations on 93 plates. 1928, ‘s Grav., NL. pp. 227-275 Description of the 16th and 17th century Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish fortresses, graves, inscriptions and other monuments on the Moluccas. The monuments are described in their historical context, with emphasis on the history of the VOC.

– Wessels, C. “De Katholieke Missie in het Sultanaat Batjan (Molukken) 1557-1609” ? In: “Historisch Tijdschrift, year 8” 427 pp. 1929, Tilburg, NL. First attempt of a description of Portuguese & Spanish roman-catholic missionary progress in the Sultanate of Batjan (Moluccas).

– Wessels, C. “De Augustijnen in de Molukken, 1544-1546; 1606-1625” In: “Historisch Tijdschrift” n°13 pp. 44-59 Bergmans & Cie, 1934, Tilburg

– Wessels, C. “De katholieke missie in de Molukken, Noord-Celebes en de Sangihe-Eilanden gedurende de spaansche bestuursoeriode 1606-1677” 141 pp. Drukkerij Henri Bergmans & Cie, 1935, Tilburg, NL.

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History