This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Written by Marco Ramerini, 2005 (English edition: 2023)

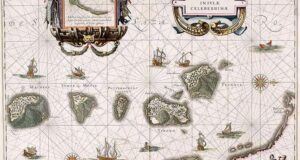

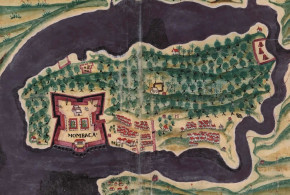

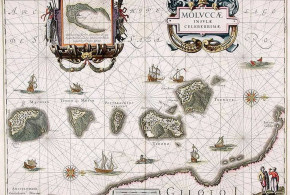

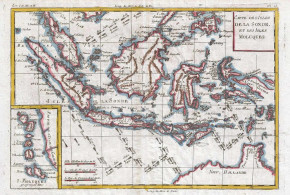

In this text I describe the information I have gathered over the years regarding the Spanish outposts in the peripheral islands of the Moluccas, therefore excluding the islands of Ternate and Tidore. Spanish control, in fact, was not limited only to the two main islands of Tidore and Ternate, which are treated in detail in my other studies.1 The Spaniards also had garrisons in numerous other islands of the Moluccas archipelago. Information about these garrisons can be found in various documents of the time kept mainly in the Archive of the Indies in Seville.

The occupation for a few years of some key points in other islands was an attempt by the Spaniards to buffer the overwhelming power of means and soldiers with which the Dutch reacted after the Spanish conquest of Ternate.2 The Dutch aimed to control the trade in cloves and nutmeg. The Spanish losers in commercial control of these goods at least tried, but without lasting success, to be able to control the basic necessities such as mainly sago and rice that were imported from Halmahera and Bacan. They also attempted to extend their control by converting the natives to Christianity. This often resulted in requests from the Christian villages of the islands for protection from the Spaniards.

In addition to a multitude of fortified posts in Ternate and Tidore, the Spanish sometimes maintained for a few years some fortified posts also in the peripheral islands of Halmahera, Morotai and Sulawesi, important posts for the maintenance of the main garrisons because they allowed the supply of sago and another indispensable food for the major garrisons and for the sustenance of the population of the islands of Ternate and Tidore, islands where due to the conformation of the land and the continuous state of war they were in, they did not allow the cultivation of these products.3

1-HALMAHERA ISLAND

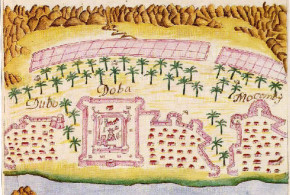

Halmahera Island is the largest island of the Moluccas. On this island the Spaniards maintained several fortified outposts for some years. This island was particularly important for the supply of food for the Spanish garrisons of Ternate and Tidore. According to Rios Coronel in 1621, the Spanish had 2 forts on the island of Halmahera.4 In my searches I found the following Spanish ‘presidios‘: San Juan de Tolo, Sabugo, Tafongo, Aquilamo, Payage and Jailolo.5

San Juan de Tolo, Toló6, Tollo

(Current name: ?) (June 24, 1606 – August 1613)

CAPTAINS OF TOLO:

Juan Cortes: June 1606-August 1606

Juan de la Torre: August 1606-(April 14, 1610 Juan de la Torre is in Tolo as head of the garrison.7

Juan de Espinosa: 1609

Francisco Bera (Vera) y Aragón (ensign):

Francisco Bera (Vera) y Aragón (ensign): -August 1613

Francisco Ribera y Aragón (ruled Tolo twice for a combined period of more than three years).

The city of Tolo is located along the east coast of the northernmost peninsula of the island of Halmahera. This part of Halmahera Island faces the southern coast of Morotai Island. This area had already been partly Christianized by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century.

In 1569, in the Portuguese era, the city of Tolo, is described by Rebelo, as not only the largest city in the Moro area, but also as the largest of all the Moluccas. Under the government of Bernaldim de Sousa (1549-1552), Tolo was fortified with the construction of “tranqueiras” and with artillery.8

In 1606, shortly after Acuña’s departure, the Spanish, commanded by Lucas de Vergara Gabiria, organized a punitive expedition against the rebels who had taken refuge in the island of Halmahera, as well as the destruction of some rebel villages, the most lasting result of this expedition was the submission and the promise of conversion to Catholicism of the city of Tolo, capital of the province of Moro and of the villages of Chiava (Cawa or Tjawa) and Samafo (Camafo).9

The city of Tolo was named San Juan de Tolo (São João do Tolo in Portuguese), because the Spaniards arrived there on June 24, 1606, the day of Saint John the Baptist. In this place, at the request of the Christians of the village, a cross was immediately erected.10

The whole area of Moro had already given good results of conversion to Catholicism during the Portuguese presence. Around twenty Spanish soldiers commanded by Juan Cortes, appointed captain of Tolo, remained in garrison of the fortress of Tolo. In August 1606, Juan Cortes was replaced as commander of the garrison of Tolo by Juan de la Torre, together with the new captain also the Jesuit father Gabriel Rengifo da Cruz arrived in Tolo.

In Tolo a church and a residence were built for the father “…San Juan de Tolo donde huvo guarnicion de Españoles, Iglesia, y doctrina…”11 and 500 people were soon baptized, given the promising beginnings of this mission, the superior of the Jesuits of Ternate, Father Luís Fernandes, also sent a second friar, Jorge de Fonseca, to Tolo, in the first nine months of the mission 1,400 people were baptized.12 The mission of S. João do Tollo (or San Juan de Tolo) is the one that seems to give the most satisfaction to the Jesuits.

In 1608, the Spaniards reinforced the defenses of the garrison of Tolo and thwarted an attempt at treason by the sangaje of Tollo, aided by that of Gamoconora.13 In 1609, the garrison of San Juan (Joan) de Tolo was under the command of Juan (Joan) de Espinosa, he commanded a troop of 40 Spanish soldiers.14

In 1610, Caerden informs the VOC administrators that the Spanish had a small fortified post at Solo (=Tolo) on the island of Halmahera.15 This fort was dismantled by Gerónimo de Silva in July 1613.16 The effective abandonment of San Juan de Tolo was completed in August 1613. The ensign Francisco Ribera y Aragón, who governed the forces of Tolo and Morotay twice and for a total period of over three years, with a letter written by him from San Juan de Tolo on August 1, 1613 proves without a shadow of a doubt that up to that date Tolo was still occupied by the Spaniards.17

The abandonment of the garrison of San Juan de Tolo caused serious damage to the reputation of the Spaniards in the islands. With the garrison of San Juan de Tolo, the Spanish controlled the whole province of Moro, which included the north coast of the island of Halmahera and the entire island of Morotai, the area where the missionaries had worked since the time of the Portuguese, it was rich in Christians (Vidaña estimates their number at 3,000, while Francisco Ribera y Aragon tells us that they are almost 2,000) and their abandonment was a serious setback for the Spaniards. All the more considering the fact that only 20 Spanish soldiers were enough to garrison it. The abandonment of such a large number of Christians caused little trust in the other natives towards the promises of the Spaniards and certainly did not favor other conversions. 18

When they left Tolo, the Jesuits moved 16 boys, sons of the leaders of the area, with them to Ternate to educate them in the Catholic faith. For this purpose, they lodged them in their house where they opened a small seminary.19

Sagugo20, Sabugu, Sabugo21, San Juan de Sabugo22:

(Current name: ?) (1611- 1613)

CAPTAINS OF SABUGO:

Juan de Espinosa y Sayas (captain): 1611-

Juan de Azebedo:

This village was also located in the northern peninsula of Halmahera, but along the south-western coast of this peninsula, just north of the island of Ternate. The village of Sabugo was conquered by the Spanish during Juan de Silva’s expedition to the Moluccas. It was located just north of Jailolo “una legua poco mas y menos de Jilolo”23

Sabugo is defined by the Spaniards as a very important fortress and village mainly because the area is rich in sago, an important source of food for the Spanish garrisons and for all the Moluccas. Captain D. Antonio de Arceo defines Sabugo “fuerza y tierra importantissima para las demas de Terrenate por ser fuerte de naturaleza y mas abundante de comida que ay en todas aquellas yslas que por su excelencia la llamaban la Pampanga de Terrenate”.24 Sabugo, was important because sago was produced there, “que es el pan de aquella tierra”25, very important food for the sustenance of the garrisons of Tidore and Ternate and for the local population.

After the conquest of Sabugo, on April 9, 1611, Azcueta appointed Juan de Espinosa y Zayas “cauo superior” of the “fuerza de Sabugo y su districto“, his task was to fortify the village and establish good relations with the local population who wanted to submit to the Spaniards.26

Even the “Meritos y servicios” of Zayas confirm that in 1611 Don Juan de Espinosa y Sayas was commander of the fort of Sabugo.27 To garrison Sabugo and to proceed expeditiously with the improvement of its fortifications, three companies of Spanish infantry and two companies of Pampanga infantry were left under the command of Juan de Espinosa y Zayas. In addition to reinforcing the existing fortifications, the Spaniards built a new fort in Sabugo located at the “boca del rio”.28

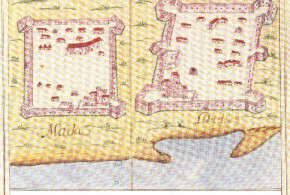

In Sabugo the Spanish had 2 fortresses “dos fuerças que su magestad tenia en el rio de Sabugo una en la boca del y otra arriba en el puerto”29 Juan de Azevedo (Azevedo), was commander of this fort.30 These two forts were dismantled by Jeronimo de Silva in July 1613.31

According to what I found, it seems that at first only one of the two forts was dismantled “lo alto de Sabugo“, which was judged as a useless fort “que ni servia ni ofendia”. The intention to abandon only that fort is expressed by de Silva in an undated letter but which may have been written between April and May 1613: “convino desmantelar lo de arriba de Sabugo dejando lo de abajo bien reparado de gente y de artilleria”. The abandonment of the fort was completed by Don Fernando de Ayala, probably between May and June 1613. The other fort was dismantled shortly after, in July 1613, after the attack launched by the Dutch on the island of Tidore, which caused great panic in de Silva. The panic that had seized the Spaniards can also be seen in the fact that they left all the artillery and all the food that was in its warehouses in the fort. The fort was burned and the artillery buried. To understand the panic and the sudden decision made by the Spaniards to abandon this fort, suffice it to say that the fort of Sabugo had been supplied a few weeks earlier with food for a year and ammunition.32

The abandonment of the two fortresses of Sabugo (“dos fuerças que su magestad tenia en el Rio de Sabugo una en la boca del y otra arriba en el puerto”) caused serious damage to the reputation of the Spaniards in the islands. With Sabugo, an important center for the supply of food for the garrisons was lost, furthermore, due to the hasty abandonment of the forts, all the artillery, ammunition and food was abandoned “… que se auian metido para un año“. According to Don Fernando de Becerra, it would have been possible to transfer most of the artillery and supplies to the nearby fortress of Jailolo in a short time. Furthermore, according to the opinion of Captain Gregorio de Vidaña, in order to be able to control Sabugo and its vital trade, it could have been enough to have kept the only fort at the mouth of the river occupied. 33

Jailolo, Gilolo34, Xilolo35, Tirolo36, Hilolo:

(Current name: ?) (1611-1620)

CAPTAINS OF JAILOLO:

Fernando Centeno Maldonado (captain): March 1611-January 1614

Pedro de Hermua (captain): January 1614-April/May 1615

Francisco de Vera y Aragon (captain): April/May 1615-

Matias de la Cruz (ensign): 1616

Juan de la Umbria: ?

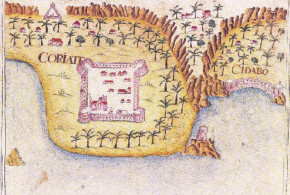

The kingdom of Jailolo was one of the four kingdoms into which the Moluccas were divided in ancient times. The kingdom of Jailolo had once been the most important in the region but already in 1500 it was in decline and controlled only the northwestern part of Halmahera, this kingdom will be practically annexed by Ternate and the Portuguese in 1551.

The expeditions of Loaisa (1527) and Villalobos (1544-1545) maintained cordial relations with the king of Jailolo and some Spanish soldiers remained in garrison of Jailolo during those times. For this reason the Portuguese attacked and destroyed, both Tidore and Jailolo, several times after the retreat of the Spanish troops.

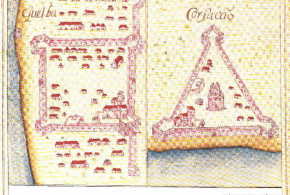

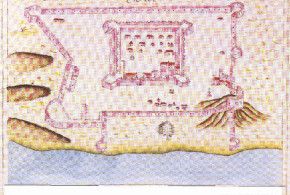

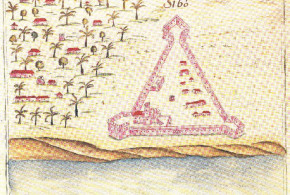

An interesting description of the fort of Jailolo before its destruction by the Portuguese in 1551 is reported to us by Diogo do Couto who describes the fortress of “Geilolo” as a large stone fortress with a triangular shape and with two large bulwarks. From a corner a “cortina” then departed from the fortress which reached a large “castello roqueiro” (probably a castle built on a rock), this castle had two bulwarks. On the side facing the sea, which was also the lowest side, another bastion was located on an “esteiro” detached from the main wall. The fortress contained 2,200 men, 100 “espingarderos”, while the artillery consisted of 18 “berços” of metal and iron. After the Portuguese victory in March 1551, the subsequent peace agreements decreed the destruction of the fortress “e que a fortaleza se havia logo de derribar por terra, e que nunca mais faria outra“. The fortress was first burned and then demolished.37

From a subsequent testimony, however, it seems that the Portuguese maintained some fortification in Jailolo, in fact a document of 1571 informs us that the Portuguese had had a fortified place here. The document that informs us of this is a letter from the Jesuit Jeronimo de Olmedo written from Ambon on May 12, 1571. He informs us that in 1570 the Portuguese fortress of Jailolo was under siege, the Portuguese soldiers having fought bravely were forced to surrender, the Portuguese garrison was then reduced to only 12 sick men and without ammunition.38

After the conquest of Ternate by Acuña, Jailolo appears to be among the strongholds ceded to the Spaniards by the Ternatese in the capitulations, signed on April 10, 1606 in the fortress of Ternate, by the sultan of Ternate39 with which the sultan handed over the fortresses he owned to the Spaniards: Xilolo (Jilolo), Sabubú, Gamocanora, Tacome, the forts of Maquién, the forts of Sula “e las demás”, the forts mentioned were to be handed over to the Spaniards with all their weapons and ammunition. The Spanish formally took possession of the fortress of Xilolo on April 14, 1606.

Despite this taking possession, Jailolo remained without a Spanish garrison and indeed became the center where the Ternatese rebels took refuge. In fact, upon their arrival in the Moluccas two Dutch ships took refuge in the port of Xilolo (Geilolo) where most of the rebels were gathered.40

In 1608, to disturb the Dutch who were busy fortifying themselves at Makian, the Spanish attacked the fortress of Jailolo, the fortress was captured and sacked, but the Spanish did not establish any garrisons there. Jailolo was then fortified again by the Ternatese with the help of some Dutch.41

Jailolo was conquered together with Sabubo in 1611 during the expedition of Juan de Silva. The expedition of D. Juan de Silva, which had aroused great hopes among the Spaniards in Ternate, limited itself only to subduing the kingdom of Jailolo (Xilolo) on the western coast of Halmahera and to conquering (at the beginning of 1611) the city of Sabugo (Sabubo) located north of Jailolo.42 In queste battaglie gli spagnoli persero 300 uomini.43 The expedition ended in a colossal fiasco that cost the state’s meager coffers over 200,000 pesos.44 From a practical point of view, however, the conquest of the two strongholds was of great importance, because the possession of Sabugo and Jilolo ensured the Spaniards an important source of food for the garrisons and at the same time the Dutch were deprived of this source of food.45

A few months after the governor’s departure for Manila, at the end of September 1611, a fleet of Dutch ships (5 ships according to G. de Silva46) arrived in the waters of the Moluccas, it was the fleet of Pieter Both. These boats headed for the island of Halmahera where they tried to bring the inhabitants of Jailolo (Tyrol) and Sabugo to their side. The population of Jailolo (Geillollo) remained faithful to the Spanish, but that of Sabugu agreed with the Dutch, despite this, the Spanish did not abandon the “posto e forte de Sabugo”.47

The Spaniards had two forts, in addition to the main fort they built another fort, called Fuerte San Xpobal or San Xpoual (San Cristobal) which was located “abajo en la marina enel agua caliente” i.e. “a la boca dela barra de Xilolo”. This fort was built in the first months of 1611 by Fernando Centeno Maldonado on the orders of Azcueta.48 Probably the full name of this fort was ‘San Xptoual de Gofaza‘. Here Juan de Medina Bermudez served as chief.49

The importance given to Jailolo by the Spaniards is indicated at the end of a letter from Juan de Silva in which he peremptorily orders not to abandon the fort of Jailolo “no desampare por ningun modo los fuertes de Gilolo y Don Gil”.50

On the island of Jailolo (Halmahera), the Spaniards have forts at Sabougo, Jailolo and Aquilamo. In all these forts the Spanish have small garrisons.

In 1613, Captain Fernando Centeno Maldonado was in charge of the fortress of Jailolo.51 On January 5, 1614, with a letter sent to Fernando Centeno Maldonado Geronimo de Silva relieves Maldonado of his position as head of Jilolo and in his place Pedro de Hermua is appointed “cauo superior en la dha fuerza de Xilolo y Cufaza (Bufaza? or Gofaza?)“. He will remain in office in Jilolo for 17 months.52 During this time he will be busy with fortifying “de piedra aquel puesto”.53

In May 1614, Captain Pedro de Hermua was commander of the garrisons of Jailolo.54 In April 1615, on the orders of Geronimo de Silva, Maldonado was in Jilolo, where Pedro de Hermua was chief. Orders were given to Hermua to hand over his company to Maldonado and leave to go to Manila. Captain Francisco de Bera (Francisco Vera y Aragon) remained in Jilolo as head of the garrison. Hermua is granted a license to go to Manila. When Maldonado returned from Manila as sergeant major and in command of a company of arquebusiers, the company was that of Pedro de Hermua, so Hermua’s rule at Jilolo ended about April/May 1615.55 Confirming this is the letter of Geronimo de Silva dated April 12, 1615 letter in which Fernando Centeno Maldonado goes to Jilolo to replace Hermua, as head of Xilolo, with Captain Francisco de Vera y Aragon. Hermua receives the order to embark with all his company.56

Some documents allow us to know who performed the function of head of the garrison: In October 1615, Captain Francisco de Vera was in charge of the fortresses of Jailolo.57 In June 1616, the ensign Matias de la Cruz was in charge of Jailolo.58

In one of his letters, Lucas de Vergara Gabiria, the Spanish governor of the Moluccas, asks for a decision to be made regarding the garrison of Jailolo, which in his opinion is useless: “Las dos fortalezas q.e su Mag.d tiene en Jilolo como Vs.A sabe no sieruen sino de tener alli ocupados ochenta soldados los sesenta españoles y cada dia ttraen muertos y enfermos …” As early as 1618, Gaviria asked the governor of the Philippines, Alonso Fajardo de Tenza, for a decision on this matter.59

The decision to abandon the two forts of Jailolo was taken a few years later, in fact shortly after the month of March 1620, the Spaniards withdrew the garrison from the two fortresses, this was done to reinforce the garrisons of Ternate and Tidore. The control of the two forts was ceded by the Spaniards to the troops of the king of Tidore, their faithful ally, but in August 1620, after repelling a first attack carried out by 30 Ternatese korakoras against the low fort (which took place on 3 August), Tidore’s troops surrendered to a Dutch ship that came to help the besiegers, the first fort to surrender was the lower fort and shortly after the higher fort also capitulated. The two forts were taken over by a garrison of Ternatese troops.60

Tafongo, Taffongo, Tanfongo61:

(1608- ?) (Current name: Kusu62)

CAPTAINS OF TAFONGO:

Martin de Montero: ? – 1611

Fernando [Hernando] Suarez: 1611

“… Tafongo que hé hun lugar do mesmo Tidore, o qual hé escala de muitos mantimentos que lhe vem da Battachina.”63

Halmahera village under the control of the kingdom of Tidore. In 1608, for fear of a Dutch attack, a Spanish garrison was placed in this fort. 64

Caerden informs the VOC administrators in 1610 that the Spanish had a small fortified post at Taffongo on the island of Halmahera.65

Martin de Montero is head of the fort of Tafongo, but he asks for permission and is granted and with a document dated January 4, 1611 he is replaced by the ensign Fernando [Hernando] Suárez.66

Payage, Payahi, Payay67, Panai68:

(1608- ?) (current name: ?)

A village located on the western coast of Halmahera east of Makian Island, at the beginning of the southern peninsula of the island. In this ‘presidio‘ called ‘Fuerça de Sant Juan de (Tosco or Toseo ?) de Payaje‘,69 for a time a Spanish garrison was maintained there.

Payage was a village in Halmahera under the control of the kingdom of Tidore. “… o lugar de Payai, que hé d’el rey de Tidore, que está na Battachina defronte de Maquien a leste”70 Here too, in 1608, a Spanish garrison was placed in this fort for fear of a Dutch attack. 71

Caerden informs the VOC administrators that the Spanish had a small fortified post at Payjay on Halmahera Island.72

Aquilamo, Aquilamme73, Aquilamma74:

(Current name: ?)

This village was also located on the western coast of Halmahera, east of Makian Island. Its importance was due to the production of sago, the staple food of the islands.75 Only in Blair, E. H. and Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” the presence of a Spanish fort with a small garrison is indicated.76

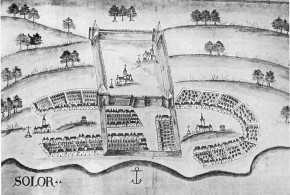

2-MOROTAI ISLAND

(Current name: Pulau Morotai)

Morotai is a large island located north of Halmahera. The island is wild and heavily forested. Even today the villages are located along the coast. The Spanish influence on the island of Morotai began in 1606 as a consequence of the progressive conversion carried out by the Jesuits which rapidly spread from the area of Tolo to the whole island of Morotai. For some years the Spaniards had a garrison on the island.

Cawo, Chawo, Chava, Chavo, Sao:

(Current name: ?) (? – 1608?)

Cawo (Chavo) is a village located in the southern part of the western coast of the island of Morotai, at the mouth of the Cawo river, here the Jesuits founded a mission and the Spaniards established a small garrison.

In 1608, the Dutch sent an expedition to the Moro area, under the command of Admiral van Caerden, they attacked and plundered the villages of Saquita and Mira all on the west coast of Morotai Island. The Spanish garrison of Chavo (Chao) was then attacked, which was also located on the island of Morotai, where a new church had recently been built.77 The Spanish garrison fought for two days and then surrendered, 8 (or 7) Spaniards were captured and about 400 indigenous Christians including the village sangage, who were deported to Ternate.78

This Spanish garrison surrendered to the Dutch in 1608.79 The population was deported to the Dutch fortress of Ternate, from where they largely managed to escape, among them was also the sangage of Chauo (Chavo, Chao), who took refuge in the Spanish fort of Ternate.80

Mira:

(Current name: Mira) (1608?-1613?)

Village located in the southern part of the east coast of Morotai, the Spaniards, after the loss of the garrison of Chavo, establish a garrison here in a “sitio muy bom”.81

Most likely this garrison was maintained until the abandonment of the province ordered by Gerónimo de Silva, in fact a passage from a declaration by Don Fernando de Becerra speaks that at the time of the government of Gerónimo de Silva “…desmantelo el presidio que se tenia en nombre de su Magestad en la provincia de San Joan de Tolo y ysla de Morotai poblada toda de gente xpiana amigos nuestros y de á donde se socorrian las fuerzas de Terrenate de muchos bastimentos y que con bien poca guarnicion de menos de quarenta hombres se sustentaua la una fuerza y la otra…” most likely “la una fuerza y la otra” mentioned are the garrison of San Juan de Tolo on the north coast of Halmahera and that of Mira on the island of Morotai.82

3-MARE ISLAND (POTTEBAKER)

(Puli Cauallo, Policaballo, Puli Caballo: Sant Miguel de la isla de Puri Cauallo). (Dutch name: Pottebackers Eyland). (Current name: Pulau Mare). (c.1650?-1662?)

CAPTAINS OF PULI CABALLO:

Diego de (Vluiarri?)83? – April/May 1662

The island in question is a small island located south of Tidore, between Tidore and Motir, and was inhabited by Tidorese population. According to what de Clercq tells us, the name Mare meant ‘stone‘ both in Tidorese and in Ternatese. The island was renowned for its production of vases (hence the Dutch name of ‘Pottebacker Eyland‘), which were made with clay from a hill located in the southwestern part of the island. The only village on the island, called Mare, was located on the east coast.84 On the island of Puli Caballo, the Spanish maintained a fort during the last years of their presence. In some documents the name of the fort is also reported: it was that of ‘Sant Miguel de la isla de Puli Cauallo’.85

Around 1650, the governor Pedro Fernandez del Rio, unable to intervene directly in aid of the king of Tidore (he was engaged in the fortification of Ternate) sent Martin Sanchez de la Cuesta to Tidore as head of the island and in charge of the main fortress of Tidore called ‘Sanctiago de los Caualleros‘, of the “fuerte Principal” (ie. the Prince (?)) and of that of Puli Cauallo.86

As for this fort, its foundation date is not certain, however, it is certain that in the years 1653 and 1654 Francisco de Estaybar rebuilt it.87In 1654 the fort was garrisoned by 8 Spanish soldiers with a chief appointed by the governor of Ternate and 24 ‘pampangos’ soldiers.88

During the period of the Tidorese rebellion (1657-1658), this fort had to endure several sieges. In 1657 the fortress, under siege, by sea and land by the Dutch, Ternatese and Tidorese rebel enemies, was rescued with the ‘capitana‘ galley by Sebastian de Villa Real. Once the Spanish galley arrived in the vicinity of the island of Puli Cauallo, it was attacked by 18 boats of the rebel ‘mori‘ and 2 ‘charruas‘ of the Dutch. The Spaniards still managed to bring relief to the fort, disembarking a troop of infantry that was attacked by the enemies but they were routed and retreated, the Spaniards thus managed to free the fort from the siege.89

Sebastian de Villa Real with the ‘capitana‘ galley brought relief to the ‘presidios‘ of Tidore and Puli Cauallo 4 times, during the period in which the ‘mori‘ had rebelled and had denied obedience to the king ‘cachil Mole‘, he rescued with the galley with food and ammunition the ‘presidios‘ of ‘Rrumen, Chouo, Tidore y Puri Cauallo’.

News of another siege of Puli Cauallo dates back to August 1658, when at a meeting of the ‘Junta‘ (which took place on August 12, 1658) presided over by the governor Francisco de Esteybar, it was decided (with an order dated August 13) to urgently send the ‘captain‘ galley, which had been beached inside the barrier to careen it, and as many boats as possible loaded with soldiers, ammunition and artillery to help the fort of Puli Cauallo. This because news had arrived that on Sunday 11 August the Dutch had left from Malayo with 10 ‘caracoas‘ and 2 ‘charruas‘ with the aim of conquering the fort of Puli Cauallo. The orders for Villareal were to attack the enemies and destroy them, doing everything possible to relieve the fort. On this occasion the Spanish fleet was made up of the ‘capitana‘ galley and two ‘caracoras‘ and was led by sergeant major Felipe de Ugalde, while in command of the ‘capitana‘ galley was Sebastian de Villa Real. The Spaniards arrived in sight of the fort on August 15, 165890, when the enemy was assaulting the port with 2 ‘charraul‘ of 8 pieces each and 12 large ‘caracoas‘, the Spaniards managed to rout the ships and make the enemies, who had landed, flee freeing the fort from the siege.

It is interesting to note that in this document, a mention is made of the Spanish fort of ‘Santa Isauel‘ (perhaps a mistake for: San Miguel ?) of the island of Puli Cauallo and its ‘rretirada‘ and ‘nuestra fuerza Santa Isauel y su rretirada en la ysla de Puli Cauallo’. Otherwise this might suggest the existence of two fortresses (as indeed in Rume and Chobo): whose names were perhaps ‘Santa Isabel‘ and ‘San Miguel‘. On another occasion, Villareal collided off Tidore with 12 ‘caracoas‘ escorted by a Dutch ship, which ‘salieron sobre Tomaloa a estoruarle‘ to prevent the arrival of relief at the fort of ‘Puri Cauallo’, despite the attack, once again the Spaniards managed to rescue the fort.91

In 1662, when most of the Spanish forts on the island of Tidore were abandoned, the garrison of the Puli Cauallo fort was also withdrawn. According to the testimony of Diego de Salazar, captain of the royal galleys of Ternate, the fortresses that the Spaniards had to demolish and the garrisons they withdrew in 1662 were those of Tidore Chouo and Puli Cauallo ‘… me ordeno retirara las de Tidore Chouo, y Puli Cauallo …’.92

Dutch sources also confirm the existence of a small Spanish fortified post. According to what is reported in the Dagh-Register 1663, it seems that the Spaniards had a “baricado” on the island (probably a small fortified position), in fact, speaking of the abandonment of the forts by the Spaniards, it is said, among other things, that the Spaniards destroyed the barricade on Pottebaker Island (“de baricado op het eyland Pottebaker gedemolieert”).93

4-MOTEL ISLAND (Moti, Motor)

(Current name: Moti)

Pulau Moti (or Motir) is a small volcanic island that lies south of Tidore and faces the western part of the island of Halmahera. The island which is about 5 km wide is dominated by a volcano which rises up to 950 meters in height.

It seems that this island (“Mutiel” island) was conquered by the Spanish during the expedition of Don Gonzalo Ronquillo, which departed from Manila in September 1582, and returned from Tidore in the Philippines in April 1583.94 But this conquest, if it really took place, had no lasting consequences.

Subsequently, in 1609, the Dutch, commanded by Vice Admiral François Wittert, built a fort (fort Nassau) on the island of Moti, located between Tidore and Maquiem (Machian). This was done because the island was rich in cloves.95

According to what Pedro de Heredia writes, this fort was dismantled by the Dutch in March 1625. However, it seems that the Spanish did not occupy the place with their own garrison.96

5-MAKIAN ISLAND (Maquién)

Makian is a volcanic island located near the western coast of Halmahera Island, between the islands of Tidore to the north and Kayoa and the Bacan Group to the south. The island is dominated by the Kiebesi volcano (or Kie Besi) whose peak reaches 1,357 meters.

Of all the Moluccas, Makian Island produced far more cloves than any other. The cause of this greater production Governor D. Gerónimo de Silva attributes it to the better propensity of the inhabitants of Makian in the cultivation of the land, unlike the natives of Ternate and Tidore who were more inclined to make war than to cultivate the fields. Makian was also the most densely populated island.97 The island was defined “la mas rica y prospera de clauo de toda aquela comarca”.98

It seems that already in 1513 (?) the Portuguese Antonio Miranda built a “fuerte o casa de madera”99

Tafsó, Tafasoho, Taffaso:

(Current name: ?) (1606 – June 21, 1608)

Located in the center of the west coast of the island was an old fortress of the king of Tidore (“que os portugueses sempre procurarão de defenderem entanto que estiverão en Tidore”100 “que os portugueses sempre procuraram de defender”.101

According to the testimony of Middleton who visited Taffaso in April 1605, the Portuguese had a small fortified house: “The 26 (April 26, 1605), we weighed, with very little wind, and plied it for Taffasoa, which standeth on the west-north-west part of the iland.” “The Portingalls have a small blockhouse, with 3 peeces of ordinance, in this towne, wherein were five Portingalls.”102

Quiros’ expedition stopped at Machian on the return journey, Prado in his description of the journey mentions the Portuguese fort of the island telling us that on the side of the Portuguese fort there was an “olla” or hidden port with an opening through which a ship can enter, but in case of winds from the north this port became dangerous and unusable.103

After 1606, the whole island of Makian was assigned to the king of Tidore. There were proposals to send a Spanish garrison to the island since Makian was the island where the largest amount of cloves was produced of all the Moluccas. But this proposal was not implemented.

In April 1607, the island of Maquién (Makian), was still without a Spanish garrison104 however, it seems that soldiers of the king of Tidore were present to garrison the island. The fortress was located on the west coast of the island. It was conquered by the Dutch on June 21, 1608. The Dutch expedition consisted of two “naos“, a “galiotta“, a “pataxo” and some “caracolas” with the help of a contingent of Ternatese. The island had been practically left unguarded105 by the spaniards106, certainly its defense was entrusted to the troops of the king of Tidore.

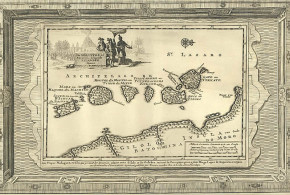

6-BACAN ISLAND

The Bacan Islands are a group of mountainous and heavily forested islands lying south of Ternate and southwest of Halmahera. The largest is the island of Bacan and on this island the Spaniards, for a short time, had a small fortification.

Labuha, Labua:

(Current name: Labuha) (1608 – November 30, 1609)

Labuha village is located in a bay in the middle of the west coast of the island.

In 1608, in Labua, on the island of Bacan, the sangage died107, given the minor age of his successor son, Paulo de Lima, a Portuguese casado, is sent with the title of sangage and village judge, with him also arrives a garrison of Spaniards to garrison the village.108

The Spanish fort was captured by the Dutch under Vice Admiral Simon Jansz Hoen on November 30, 1609.109 On November 30, 1609, the Dutch commanded by Captain Simon Jansz Hoen occupy the island of Bacan, conquering the small Spanish fort of Labuha.110 In the fight 16 Spanish soldiers are killed “sin otros naturales”.111

According to what Pedro de Heredia writes, in April 1625, the Dutch probably also dismantled the fortress of Bachian “Y al presente an ydo a rretirarla del Reyno de Ba(?)jan”.112

7-SANGI ISLAND, SANGUIL

(Current name: Sangihe or Sangir Besar)

This is the largest island in the island chain which from the northern tip of Sulawesi extends north to the Philippines. The island is made up of various volcanoes including Mount Awu, an active volcano over 1,300 meters high.

The island of Sanguil was in the seventeenth century divided between four kingdoms: Maganitos, Tabucan, Calonga and Siao. The king of Siao island controlled the villages of Tabacos, while the kingdom of Calonga controlled the two villages of Calonga and Tarruma, in the latter village for a time the Spanish maintained a garrison of 10-12 Spanish soldiers. The garrison was maintained to defend the two villages which were inhabited by Christians. After the abandonment of Ternate by the Spaniards, the village of Tarruma placed itself under Dutch protection, and it seems that a preacher lived here with some Dutch, while the other village, Calonga, instead remained faithful to the Spaniards.

Taruna:

(Current name: Tahuna)

Spanish garrison with 10-12 soldiers, “donde estava una fuerzecilla nuestra”113

8-SIAU ISLAND

(Current name: Pulau Siau)

The island of Siau is located in the Sangir archipelago about 130 km north of the extreme offshoot of the island of Sulawesi (Celebes). The island is characterized by the presence, in its northern part, of a large volcano, the Karangetang (Api Siau), 1,827 meters high, and one of the most active volcanoes in Indonesia.

On this island, thanks to the work carried out, starting from 1604, by Father Antonio Pereira, there were many conversions to Christianity.

Kauhise, Caiuhice, Santa Rosa:

(Forte Santa Rosa) (Current name: ?) (1671- November 1677)

The island was one of the most Christianized in the area and it was for this reason that the Spanish presence on this island was maintained for a few years longer than in the rest of the Moluccas. In 1671, a small Spanish garrison (a chief with 14 soldiers) was sent to the island of Siau, for the protection of the king of the island, Francisco Xavier Batahi. They built the fort called Santa Rosa. In 1677 when the Dutch conquered the island, the Spanish garrison was taken prisoner and with them three Jesuits were captured, the friars Cebreros, Esapañol and Turcotti, both the soldiers and the friars were first transported to Ternate and then to Manila.114

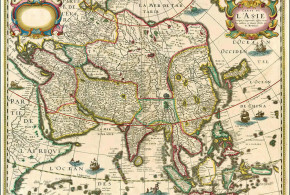

9-SULAWESI ISLAND (CELEBES)

Manados:

(Current name: Manado) (1617-1621 ?/1624 ?- ?)

The Spaniards had contact with the northern region of the large island of Sulawesi (Celebes) since the conquest of Ternate in 1606. In the following years, the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries115 had some success in converting part of the population to Christianity.

In 1617, a small fortification was built on the orders of Lucas Vergara Gabiria, for the purpose he sent 10 soldiers under the command of Francisco Melendez.116 In order to secure the flux of provisions from the island of Celebes, the Spaniards decided to build a fortress in Manados, for this purpose an expedition made up of 10 soldiers was probably sent in May 1617 by Vergara Gaviria under the orders of Francisco Melendez and two Jesuits (the two Jesuits were Gianbattista Scalamonti and Cosme Pinto). The Spanish built a small fortified post.117

The garrison of Manados was evacuated during the rule of D. Luis de Bracamonte (probably in 1621). The Spanish garrison appears to have been resettled by Governor Pedro de Heredia (1624?).118

Tomohon, Tomun:

(Current name: ?) Village located in the interior of Sulawesi about 20/25 km from Manando.

Here it seems that there was a small Spanish garrison.119

Bohol, Bool:

Probably today’s village of Buol, located on the north coast of Sulawesi, near Cape Kandi in Bilang Bay, between Tolitoli and Kuandang. A first contact between the Spaniards and the kingdom of Bool already took place in 1606 when Juan de Esquivel sent an expedition to the island of Mateo (Celebes) consisting of a “galeota“, a brigantine and some other small boats at the command of which was the standard-bearer Cristobal Suárez. The purpose of this expedition was to receive acts of vassalage towards the king of Spain from the peoples previously subject to the dominion of Ternate. The kings of Bool, Totoli and the queen of Cauripa submitted to Spain.120

In the last days of July 1614, at the express request of the king of Bohol, Gerónimo de Silva from Ternate sent a contingent of soldiers to Bohol made up of 3 soldiers and 3 ensigns led by the ensign Juan Fernandez, two Franciscan religious were also part of the expedition “uno sacerdote y otro lego”.121

NOTES:

1 Ramerini Marco “The Spanish forts on the island of Tidore 1521-1663” colonialvoyage 2000/2005 https://www.colonialvoyage.com/spanish-fortresses-island-tidore-1521-1663/ ; Ramerini Marco “The Spaniards in the Moluccas ((1521) 1606-1663/1671-1677). The history of the Spanish presence in the spice islands” colonialvoyage 2000/2005 https://www.colonialvoyage.com/i-primi-contatti-degli-spagnoli-con-le-isole-molucche/ ; Ramerini Marco “The Spanish presence in the Moluccas: The fortifications of Ternate” colonialvoyage 2005 https://www.colonialvoyage.com/spanish-presence-moluccas-ternate-tidore/ ; Ramerini Marco “Fortificaciones españolas en Ternate y Tidore” Chapter IV in: En el Archipielago de la Especieria Espana y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII – 2021, ISBN 978-84-122212-2-0 ; Juan Carlos Rey, Antonio Campo, Marco Ramerini “The fortresses of the Moluccas islands: Ternate and Tidore” 2022, ISBN: 978-84-124434-2-4.

Note to the English translation: Very interesting on the subject are the recent studies of Antonio Campos Lopez (which I quote below) and the new book by Simon Pratt “Spice Islands Forts“.

2 Campo Lopez Antonio “Enclaves españoles en Halmahera y Sulawesi” in “En el Archipielago de la Especieria Espana y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII”, Madrid 2021, Desperta Ferro.

3 Ramerini Marco “The Spanish forts on the island of Tidore 1521-1663” colonialvoyage 2000/2005 https://www.colonialvoyage.com/spanish-fortresses-island-tidore-1521-1663/

4 Rios Coronel, Hernando de los “Memorial y relacion…” 1621, Madrid, Spain. In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 19 (1620-1621), p. 288

5 Note to the English translation: As regards the Spanish forts on the island of Halmahera, a very interesting and detailed study has been made in recent years by Antonio Campo Lopez: “Los fuertes españoles en la isla de Halmahera: los fuertes de la banda del sur” and “Los fuertes españoles en la isla de Halmahera: los fuertes de la banda del norte“.

6 Correspondencia p. 316, 317

7 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de San Salvador de Palo, etc.Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de San Salvador de Palo, Sampoetan y Ormoc en Leyte a Hernando del Castillo. Resuelto, [f] 1623-08-11” FILIPINAS,47,N.58 Blocco 2 foglio 6-7

8 Rebelo, Gabriel “Informaçam das cousas de Maluco” in: “Documentação…..” vol. VI p. 208

9 On the Spanish attack on the island of Halmahera see: Ramerini Marco “The Spaniards in the Moluccas ((1521) 1606-1663/1671-1677). The history of the Spanish presence in the spice islands” colonialvoyage 2000/2005 https://www.colonialvoyage.com/il-governo-di-juan-de-esquivel-a-ternate-1606-1609/ . (Doc.Mal. III pp. 61-69 Doc. n°16)

10 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 118 Doc. n°35)

11 (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 570 nota n°1)

12 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 61-69 Doc. n°16) (Doc.Mal. III pp. 118 nota 11) and (Doc.Mal. III pp. 122-125 Doc. n°35)

13 (Doc. Mal. III p. 153 Doc. n°38)

14 AGI: Mexico 28, N.2 “El sargento mayor Cristobal de Azcueta al gobernador de las Filipinas Don Juan de Silva, sobre el estado de las fuerzas a su cargo, Terrenate 23 aprile 1610”

15 de Booy “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden uitgezeild in 1606” vol. II p. 239 “Copie van het scrijven van Paulus van Caerden aan de bewindhebbers dd. 17 juni 1610”

16 Wessels “De katholieke missie in de Molukken..” p. 51

17 (Doc.Mal. III p. 255 Doc. n° 66 & p.297 Doc. n° 78) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 569 note n°1; pp. 571-572 nota n°1)

18 (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 266-267 nota n°3; p. 315 nota n°1; p. 571 note n°1) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 266 note n°3 “Declaración jurada del capitan Gregorio de Vidaña, 4-08-1618”)

19 (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 570 nota n°1)

20 Correspondencia p. 321, 322

21 “Letter by D. Gerónimo de Silva to the King Felipe III, Ternate, April 13, 1612” In: Correspondencia p. 8, 10

22 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Masbate. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de la isla de Masbate en Ibalon (Albay) a Fernando [Hernando] Suárez. Resuelto, [f] 1623-11-22” FILIPINAS,47,N.65 block 2 sheet 13

23 AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18

24 Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 264 note n°1

25 Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 264 note n°1; Declaration of Pedro de Heredia, AGI Filipinas: 67-6-37

26 AGI: “Carta di Azcueta, Sabugo, 9 aprile 1611” in AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Bongol, etc. Juan de Espinosa y Zayas. 10-10-1618” Filipinas,47,N.11

27 AGI: “Méritos y servicios Fernando de Ayala Filipinas, 23-07-1622” Patronato 53 R.25

28 “Letter from Fernando de Ayala, Terrenate, May 1, 1613” in AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Bongol, etc. Juan de Espinosa y Zayas. 10-10-1618” Filipinas,47,N.11

29 Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 266 note n°3

30 AGI “Meritos: Juan de Azevedo, 1625” Indiferente, 111, N.56

31 Wessels “De katholieke missie in de Molukken..” p. 51 e Appendix B “Early years of the Dutch in the East Indies” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 15 p. 325

32 Correspondencia p. 103, 135, 148, 150, 156

33 On the abandonment of some Spanish forts on the island of Halmahera see: Ramerini Marco “The Spaniards in the Moluccas ((1521) 1606-1663/1671-1677). The history of the Spanish presence in the spice islands” colonialvoyage, 2000-2005, https://www.colonialvoyage.com/il-governo-di-d-jeronimo-de-silva-a-ternate-1612-1617/ .(Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 266-267 note n°3; p. 315 note n°1; p. 571 note n°1) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 266 note n°3 “Declaración jurada del capitan Gregorio de Vidaña, 4-08-1618”)

34 Correspondencia p. 174, 319, 323, 324

35 (“Letter from D. Gerónimo de Silva to King Felipe III, Ternate, April 13, 1612” In: Correspondencia p. 10)

36 (“Letter from D. Gerónimo de Silva to King Felipe III, Ternate, April 13, 1612 In: Correspondencia p. 8)

37 (Couto, Diogo “Da Asia” decada VI parte II pp. 299-324)

38 (Doc. Mal. I p. 626 e note 31) (on this episode see also Couto “Da Asia”)

39 (See: Doc. 7027 from the Archivio de Indias in Seville “Capitulaciones que por disposición del general de esta armada Don Pedro de Acuña hicieron con el rey de Terrenate el General Juan Juárez Gallinato y el capitán Cristóbal de Villagra. Fortaleza de Terrenate, 10 de abril [1606]” . 1-2-1/14, r.o 5 (fs. 109))

40 (Argensola p. 347)(Malucas y Celebes p. 685)

41 On the Spanish attack on Jailolo see: Ramerini Marco “Gli Spagnoli nelle Isole Molucche (The Spaniards in the Moluccas), 1606-1663/1671-1677” colonialvoyage, 2005-2020, https://www.colonialvoyage.com/il-governo-di-cristobal-de-azcueta-menchaca-a-ternate-1610-1612/ . (Doc. Mal. III p. 135 Doc. n°38)

42 (Doc. Mal. III p. 197-198 Doc. n°55)

43 (Montero y Vidal p. 159)

44 (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 262-263 note n°1)

45 On the 1611 Spanish attack on Halmahera see: Ramerini Marco “Gli Spagnoli nelle Isole Molucche (The Spaniards in the Moluccas), 1606-1663/1671-1677” colonialvoyage, 2005-2020, https://www.colonialvoyage.com/il-governo-di-cristobal-de-azcueta-menchaca-a-ternate-1610-1612/

46 (“Letter by D. Gerónimo de Silva to the King Felipe III, Ternate, April 13, 1612” In: Correspondencia p. 7)

47 (Doc. Mal. III p. 213 Doc. n°59)

48 (AGI: “Informaciones: Fernando Centeno Maldonando, 1616. Certificacion del maestro de campo Xpoual de Axqueta Menhaca” Filipinas, 60, N. 18) (AGI: “Expediente de confirmacion … Pedro de la Fuente Uriez” Filipinas, 48, N. 39)

49 (AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Guisan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Guisan, Lantac, Adpili, Panglao, Masago, Panaon y Ormoc en Cebu en Leyte a Juan de Medina Bermudez. Resuelto, [f] 1633-08-12” FILIPINAS,48,N.67 block 1 sheet 21)

50 (Correspondencia p. 174)

51 (Correspondencia p. 124, 132, 176)

52 (Letter by Geronimo de Silva Ternate, January 4, 1614 in: AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc Pedro de Hermua, 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28)

53 (“Titolo de almirante de las naos de Nueva España” in AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc Pedro de Hermua, 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28)

54 (Corrispondencia pp. 216-217)

55 (AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18)

56 (Letter by Geronimo de Silva Ternate, April 12, 1615 in: AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc Pedro de Hermua, 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28)

57 (Correspondencia p. 325)

58 (Correspondencia p. 376)

59 (AGI; Filipinas,7,R.5,N.53 In: “Carta de Alonso Fajardo de Tenza sobre asuntos de gobierno” “Copia de carta de Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, gobernador de Terrenate, al gobernador de Filipinas, sobre las dificultades que encuentra para la compra de clavo; las conversaciones con el rey de Tidore que le comunicó que los naturales de Vanda junto con los ingleses habían dado ponzoña a los holandeses causando muchos muertos; el estado de las fuerzas; la falta de cirujano, y de la presencia de tres naos del enemigo.” Tídore 30 de junio 1618.)

60 (Tiele, P.A. “De Europeans in the Malayan Archipelago, 1618-1623” pp. 272-273)

61 Doc. Mal. III pp. 275-276

62 Campo Lopez Antonio “Enclaves españoles en Halmahera y Sulawesi” in “En el Archipielago de la Especieria Espana y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII”, Madrid 2021, Desperta Ferro

63 Doc. Mal. III p. 147

64 (Doc. Mal. III p. 147 Doc. n°38)

65 de Booy “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden uitgezeild in 1606” vol. II p. 239 “Copie van het scrijven van Paulus van Caerden aan de bewindhebbers dd. 17 juni 1610”

66 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Masbate. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de la isla de Masbate en Ibalon (Albay) a Fernando [Hernando] Suárez. Resuelto, [f] 1623-11-22” FILIPINAS,47,N.65 blocco 2 fogli 8-9

67 Doc. Mal. III p. 135

68 Doc. Mal. III p. 136

69 AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Santa Catalina. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Santa Catalina a Alonso Serrano. Resuelto. [f] 1638-09-19” FILIPINAS,49,N.25 block 2 sheets 5-7 Declaration of Juan de la Umbria (Terrenate, 14 junio 1614)

70 Doc. Mal. III p. 147

71 (Doc. Mal. III p. 147 Doc. n°38)

72 de Booy “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden uitgezeild in 1606” vol. II p. 239 “Copie van het scrijven van Paulus van Caerden aan de bewindhebbers dd. 17 juni 1610”

73 (“Informatie van den stant van de Molucques, door Jan Bruyn, 12 may 1609” In: “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azie, 1607-1612” vol. II p. 320)

74 (“Informatie van den stant van de Molucques, door Jan Bruyn, 12 may 1609” In: “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azie, 1607-1612” vol. II p. 320)

75 “Informatie van den stant van de Molucques, door Jan Bruyn, 12 may 1609” In: “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azie, 1607-1612” vol. II p. 320

76 Appendix B “Early years of the Dutch in the East Indies” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 15 p. 325

77 (Doc. Mal. III pp. 145 Doc. n°38 & Doc. Mal. III p. 171 Doc. n°44)

78 (Doc. Mal. III pp. 139-140 & 145-146 Doc. n°38)

79 (Doc. Mal. III p. 140 Doc. n°38)

80 (Doc. Mal. III pp. 146 Doc. n°38)

81 (Doc. Mal. III p. 141, 154 Doc. n°38)

82 (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 315 nota n°1)

83 In 1662, he was in charge of the fort of ‘San Miguel’ of ‘Puli Cauallo’, in April/May 1662 he was appointed head of the fort of Rume. “Confirmación de encomienda de Tagui, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Tugui (sic por Tagui)por otro nombre Masinloc, Sigayan, Ala Alan, Buquil, Bolinao y Agno en Pangasinan a Nicolás Jurado. Resuelto. [f] 28-04-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.3

84 De Clercq F.S.A. “Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate, 1890” (Leiden, 1890) 76-78

85 “Confirmación de encomienda de Tagui, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Tugui (sic por Tagui)por otro nombre Masinloc, Sigayan, Ala Alan, Buquil, Bolinao y Agno en Pangasinan a Nicolás Jurado. Resuelto. [f] 28-04-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.3. “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Abucay y Samal en Pampanga a Diego Cortés. Resuelto. [f] 12-05-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.9 sheet 93

86 (In: “Confirmación de encomienda de Caraga, etc, Martín Sánchez de la Cuesta, [f] 1659-06-19” AGI FILIPINAS,51,N.1 fogli 56-60, 64-68)

87 “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Abucay y Samal en Pampanga a Francisco de Esteybar. Resuelto. [f] 17-12-1661” AGI: Filipinas,51,N.14

88 “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Palanan en Tayabas a Pedro Lozano. Resuelto. [f] 02-05-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.6

89 “Certification of the sergeant major don Sebastian de Villa Real” (Manila, September 20, 1673) (sheets 18-21) in: “Confirmación de encomienda de Majayjay, etc. Expediente de confirmacion de las encomiendas de Majayjay y Santa Cruz en La Laguna de Bay a Juan Rodríguez de Origuey. Resuelto[f]. 1695-06-08” AGI: Filipinas,58,N.3

90 In the document it is written 1659, but it is probably an error by the copyist for 1658, since all other testimonies always indicate the fact as having occurred in 1658.

91 “Confirmación de encomienda de Mambusao. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Mambusao en Panay a Sebastián de Villarreal. Resuelto. [f] 19-05-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.11

92 “Confirmación de encomienda de Majayjay, etc. Expediente de confirmacion de las encomiendas de Majayjay y Santa Cruz en La Laguna de Bay a Juan Rodríguez de Origuey. Resuelto[f]. 08-06-1695” AGI: Filipinas,58,N.3. Memorial of the ensign Juan de Origuey (Manila, September 20, 1673) (fogli 18-20) in: “Confirmación de encomienda de Batangas. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Batangas en Balayan a Lorenzo de Zuleta. Resuelto. [f] 03-04-1677” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.14

93 (Dagh-Register 1663 p. 240) See: sheets 88 and 118: “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc Francisco de Esteybar [c] 1661-12-17” AGI: Filipinas,51,N.14

94 (Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo VI (1608-1618) pp. cxix-cxx)

95 (Doc. Mal. III p. 161 Doc. n°41)

96 (AGI: Filipinas,20,R.19,N.122 “Pedro de Heredia sobre situación de Terrenate 4-04-1625”) (Generale Missiven I p. 217)

97 (“Letter by D. Gerónimo de Silva to the King Felipe III, Ternate, aprile 13, 1612” In: Correspondencia p. 7)

98 (AGI: “Carta de Rodrigo de Vivero al Rey conquista de Maquén, 25-08-1608” Patronato,47,R.27)

99 (Argensola p. 23)

100 (Doc. Mal. III p. 148 Doc. n°38)

101 (Doc. Mal. III, p. 135 Doc. n°38)

102 (Middleton p. 40)

103 (Prado p. 22)

104 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 70-75 Doc. n°17)

105 “que estava sem presido de espanhoes” (Doc. Mal. III pp. 135 Doc. n°38)

106 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 98-107 Doc. n°30) e (Doc. Mal. III pp. 135 Doc. n°38).

107 Chief of the island or village.

108 (Doc. Mal. III p. 138 Doc. n°38) e (Doc. Mal. III p. 152 Doc. n°38)

109 (Doc. Mal. III p. 176 Doc. n°48, nota 7)

110 (Doc. Mal. III p. 8*) e (Doc. Mal. III p. 176 Doc. n°48, nota 7)

111 (Doc. Mal. III p. 180 Doc. n°48A)

112 (AGI: Filipinas,20,R.19,N.122 “Pedro de Heredia sobre situación de Terrenate 4-04-1625”)

113 (Doc. Mal. III p. 662 and note 14)

114 (Doc.Mal. III p. 2* & 18*-19*)(Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 813 note n°1)

115 See: Campo Lopez Antonio “Enclaves españoles en Halmahera y Sulawesi” in “En el Archipielago de la Especieria Espana y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII”, Madrid 2021, Desperta Ferro pag. 112 and also: Sanchez Fuertes Cayetano “Los franciscanos en las Molucas y Célebes” in “En el Archipielago de la Especieria Espana y Molucas en los siglos XVI y XVII”, Madrid 2021, Desperta Ferro.

116 (Doc.Mal. III p. 412 nota 3) (Perez “Malucas y Celebes” p. 428)

117 (Perez “Malucas Y Celebes” p. 428) (Doc. Mal III p. 412 note 3) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 572 note n°1)

118 (Pérez pp. 623, 627-628) (AGI: Filipinas,7,R.5,N.65 “Carta de Fajardo de Tenza sobre asuntos de gobierno, 10-12-1621”)

119 (Doc. Mal. III p. 661 doc. n° 215 and note n° 10)

120 (Argensola p. 349-350)

121 (Correspondencia pp. 227-228, 234-235, 283-284)

This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History