This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster.

Shortly after the Union of Spain and Portugal, Philip II imposed the ban on the Dutch to trade and use the Iberian ports, this act was the result of the Dutch rebellion against the Spanish king, and it suddenly kept the Dutch away from the supply of goods from the rich colonies of these two countries.

Philip II believed by doing so he would give a final and hard blow to the ambitions of the Dutch, but the ban had the opposite effect. In fact the Dutch traders were encouraged to attack the overseas possessions of the Iberian monarchy in order to bypass the blockade imposed on them and with the risky but ambitious goal of controlling the commercial overseas market themselves instead of their enemy Philip II.

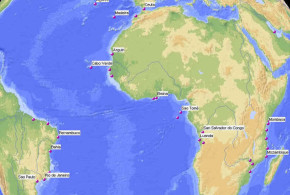

Owing to this fact the first Dutch expeditions along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea took place. In 1596 an expedition equipped by the Zeeland commercial house Moucheron attacked, without success, the Castle of São Jorge da Mina on the Gold Coast (now Ghana), being the main base of the Portuguese in the area.

The Dutch traders, who had begun to frequent the area of the Gulf of Guinea, making fierce competition to the Portuguese traders, were able to exclude them from trade in gold, ivory, wax and pepper after about 15 years. Only the slave trade was for the time being under the control of the Portuguese, but only because the Dutch were not interested in this trade at that time.

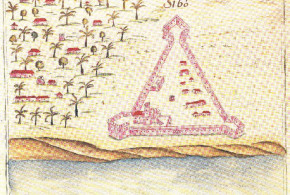

The Dutch, after the failed attack on the main Portuguese fort of São Jorge da Mina, thought that the island of Príncipe could be a useful base of support in the area, and organized for this purpose an expedition against the island.

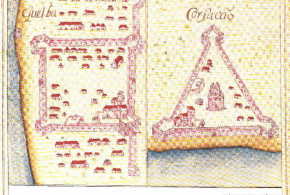

Even this expedition was sent by the commercial Zeelandese house Moucheron, which saw the conquest of the island of Príncipe as a springboard for further expansion in the Gulf of Guinea and the next possible conquest of the rich sugar island of São Tomé, which was the main objective. According to these plans a fortress was to be built on the island of Príncipe.

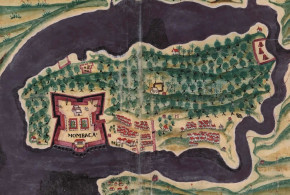

The expedition, which consisted of five ships under the command of Cornelis van Moucheron, arrived on Príncipe island in August 1598 and with a surprise attack the Dutch occupied the island. Once occupied the island, the necessary construction material for the fortress was brought ashore. It had been specially brought along from Holland. Under the command of Cornelis van Moucheron, who was appointed governor of the island, had begun the construction work. Unfortunately for the Dutch, who apparently were rather unfamiliar with the area: The rainy season had begun. This led to unhealthy air. So many men of the expedition became ill and some died of marshfever. The bad weather and attacks from the Portuguese of São Tomé forced the Dutch to abandon the island of Príncipe after about three months of occupation.

Despite this fiasco the following year in October 1599 a new larger expedition arrived this time on the island of São Tomé. The new navy force was composed of 36/40 ships commanded by Pieter van der Does. Partly it was equipped by Moucheron, too.

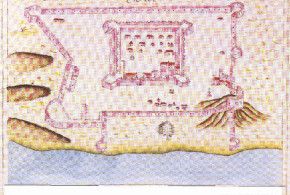

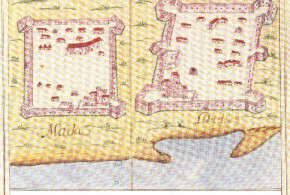

São Tomé was defended by a militia formed by the inhabitants and slaves and by a small fort, Fort São Sebastião that could not provide adequate protection to the people and the city, it was equipped with little artillery, only six small guns and two mortars, had little gunpowder and lacked a garrison of professionals. According to Portuguese sources the only professional soldier of the entire island was a sergeant-major.

On 18 October 1599, early in the morning, the Dutch fleet came in sight of São Tomé, despite the fact that the Portuguese had known for a few weeks of the arrival of the Dutch fleet it seems that little had been done to improve the island’s defenses. Dutch ships arrived in the port and began to bombard the city. By mid-morning it was evacuated by the Portuguese, who hid inside the island. But a small contingent of about 20 people – including the Portuguese governor Fernando de Meneses – were trapped in the fort resisting the Dutch for another three hours and then surrendered. Finally the Dutch took over the fort.

Meanwhile the Portuguese fled from the city, got reorganized under the command of João Barbosa da Cunha and tried a counterattack on October 20. According to Portuguese sources the attack was done to force the Dutch to withdraw. On the other hand according to Dutch sources the reason for the failure of the Dutch expedition was to be found in the unhealthy climate of São Tomé. In fact also this time the Dutch had chosen the most unfavourable season being the beginning of the rainy season (lasting from October to June) with regular equatorial rains, which caused disease among the Dutch troops. In a few days about 1,200 men died, including the commander of the expedition Pieter van der Does. After two weeks the rest of the expedition abandoned São Tomé, but not before setting fire to the town and having pillaged and destroyed the fort and burned churches and farms of the island.

The Dutch attack was a blow to the island’s economy, because it was preceded by some events that had already undermined the prosperity of the island: in 1574 there was an onslaught of “Angolares”¹ against the north of the island, when several sugar cane plantations and many farms were destroyed. In 1585 a fire devastated the city of São Tomé and in July-August 1595 a major slave revolt occurred, which was led by a certain Amador, who set fire to the island for several weeks.

End of part one. Soon to be followed by a second part.

NOTES: ¹Angolares: Bantu Negro race, coming from Angola, who lived in the forests and mountains in the south of the island. There are several theories about their origin: some say it were black slaves who had escaped from the plantations, but others argued that they were slaves on board a slave ship wrecked off the coast of the island and who had managed to escape from the wreck, then there are those who think that they were the first settlers, who had reached the island before the arrival of the Portuguese.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

– Garfield, Robert “A history of São Tomé Island, 1470-1655. The key to Guinea” San Francisco, 1992

– Ratelband, Klaas “Nederlanders in West-Afrika (1600-1650). Angola, Kongo en São Tomé” Portuguese edition: “Os Holandeses no Brasil e na costa africana. Angola, Congo e São Tomé (1600-1650)” Lisboa, 2003.

This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History