Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster.

The history of the Dutch in Ceylon began during the command of Admiral Joris van Spilbergen on 31 May 1602, when the first Dutch ships, which visited Ceylon, anchored off the port of Batticaloa.

The Portuguese under Afonso de Albuquerque started right from the beginning with the experiment of a colonisation based on settlements of Portuguese citizens called “casados”. Since the Portuguese women were few, mixed marriages were encouraged between the Portuguese and the Asians. Albuquerque tried to create a new Portuguese nation in Asia to compensate for the lack of people from Portugal.

This method of settlement was extremely successful. In fact, after a century of this colonisation, in practically every outpost of the empire, there were colonies of mixed Portuguese, who spoke Portuguese, were Catholic and were better suited to the tropical climates than the European-born Portuguese. Thanks to this strategy, the Portuguese succeeded in withstanding the siege of the Dutch in Ceylon for nearly 60 years.

After their conquest the Dutch also attempted to found some colonies of Dutch citizens dubbed “Burgher”. This was particularly attempted for the first time under Maetsuyker (governor from 1646 to 1650), but at the end of his government and later under Van Goens (governor from 1662-1663 and 1665-1675), there were only 68 married Free-Burghers on the island. Such policy was clearly a failure as only a few Dutch families settled on the island. During the first 30 years of Dutch rule in Ceylon, the Burgher community never exceeded 500 in number and it was mainly composed by sailors, clerks, tavern-keepers and discharged soldiers.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) encouraged the Burghers by supporting this type of emigration to Ceylon in any case: Burghers alone had the privilege to keep shops, were given liberal grants of land with the right of free trade. Whenever possible they were preferred to natives for appointment to an office. Only Burghers had the right of baking bread, butchering and shoemaking. Most of them were civil servants of the Company. The marriage between a Burgher and a native woman – often an Indo-Portuguese woman – was only permitted, if she professed the Christian religion. However, the daughters of this union had to be married to a Dutchman. Like Van Goens said: “… so that our race may degenerate as little as possible”.

In the XVIIIth century a growing European community (a mixture of Portuguese, Dutch, Sinhalese and Tamil) had developed in Ceylon. They dressed like a European, were adherents of the Dutch Reformed Church and spoke Dutch or Portuguese. With the passing of time, the Burgher community developed into two different communities: Dutch Burghers and Portuguese Burghers.

The Dutch Burghers were those, who could demonstrate European ancestry (Dutch or Portuguese) through the male line, were white, Dutch Reformed and Dutch-speaking. The Portuguese Burghers (called later Mechanics) were those, who had a supposed (but not sure) European ancestry, had dark skin, were Catholics and spoke Creole Portuguese. The European community supplied the clergy (predikante) of the Dutch Reformed Church. In the last decades of Dutch rule on the island, the Burghers formed a detachment of citizen soldiers. They defended the ramparts of Colombo during the fourth Anglo-Dutch War.

Although there are no demographic studies available on the Burgher community in Ceylon during the Dutch period, it is clear that the growth of the community was constant. A small, but steady influx of newcomers from Europe mixed with the families, who had settled on the island for generations. Thanks to this, the Burgher community was able to retain its open character and the heterogeneous cultural traditions.

At the time of the British conquest, in 1796, there were about 900 families of Dutch Burghers residing in Ceylon, concentrated in Colombo, Galle, Matara and Jaffna. During the British times the Burghers were employed in the Colonial administration like clerks, lawyers, soldiers, physicians, and were a privileged class on the island. The Dutch Burghers, now under the British, quickly abandoned the use of the Dutch language and adopted English as their own language. By 1860 the use of Dutch among the Dutch Burghers had disappeared. In 1908 only six or eight Dutch Burghers could still pretend to know the Dutch language, whereas the Creole Portuguese continued to be used amongst the Dutch Burghers’ families as the colloquial language until the end of the XIXth century.

In 1899 the Dutch Burgher community formed the “De Hollandsche Vereeniging” and later, in 1907, they founded the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon. The Dutch Burgher community had its own journal from 31 March 1908 to 1968 (58 numbers), the Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon. No volumes were published between 1968 and 1981, mostly due to the exodus of many Dutch Burghers. Now the Journal continues to be published annually.

By the end of the British rule the Dutch Burgher community had lost its influence and privileges, and many Burghers emigrated to Australia or Canada, especially after the declaration of Sinhala as the official language (1956) of the country by Solomon Bandaranaike. In spite of this the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon is still in existence in Colombo to this day. The Dutch Reformed Church is now called the Presbyterian Church of Ceylon, the membership presently being 5,000. On the whole island you find 24 congregrations and 18 ministers of this Church. During the last 40 years the Church has lost much of its leadership and membership due to mass emigration of the Dutch Burgher community.

These are some of the usual surnames in the Dutch Burgher community: Andriesz, Anthonisz, Antonisse, Arndt, Bagot Villiers, Baldesinger, Bartholomeusz, Beekmun, Beven, Brohier, Claasz, Crozier, Da Silva, Daniels, de Hoedt, de Kretser, De Zilwa, Deutrom, Ebert, Engelbrecht, Foenander, Frugtniet, Hepponstall, Herft, Jansz, Joseph, Keegal, Kelaart, Landsberger, Loos, Lourensz, Martinus, Melder, Meynert, Milhuisen, Neydorff, Passe, Peiris, Philipsz, Prins, Scharenguivel, Scharff, Spittel, van Arkadie, van Cuylenburg (Culenberg), van Dersil, van der Straaten, van Dort, van Hoff, Van Langenberg, Van Rooyen, Vander Gucht, Werkmester, Wille, Willenberg.

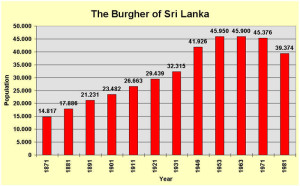

THE BURGHERS COMMUNITY IN THE SRI LANKA CENSUS

At the census of 1871 the Burghers were 14.817. At the census of 1901 there were 23.482 Burghers and 6.300 “other” Europeans. At the census of 1921 there were 29.439 Burghers and at that of 1946 there were 41.926 Burghers (0,8 % of the entire population). At the census of 1963 there were 45.900 Burghers (totalling 0,43 %).

At the census of 1981 the Burghers (Dutch and Portuguese) were 39.374 (0,3 % of the population). About 80 % of them were able to speak English, 72 % could speak Sinhalese and 18 % Tamil. About 72 % of the Burghers lived in Colombo.

At the census of 2001 the Burghers (Dutch and Portuguese) were 35.283 (0,2 % of the population), from the result of this census were excluded the areas of Jaffna, Trincomalee and Batticaloa.

According with the Basic Population Information of 2007 in the district of Batticaloa the Burghers were 2412 (0,5%), in Ampara district the Burghers were 929 (0,2%), in Jaffna district the Burghers were 8 (0,0%), in Trincomalee district the Burghers were 967 (0,3%).

At the census of 2011 the Burghers (Dutch and Portuguese) were 37.061 (0,18 % of the population), from the result of this census were excluded the areas of Jaffna, Mannar, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, Kilinochchi, Batticaloa and Trincomalee.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

– Various Authors “Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon” JDBUC ??? vol. 1-57 index in vol. 58 (1968) Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon 1908-1968 Colombo

– Brohier, Deloraine “The Dutch Burgher Union of Ceylon – its founding and growth” Article in “Daily News” 17-10-1998, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

– Brohier, Deloraine “Who are the Burghers ?” Article in: “Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Sri Lanka” Vol. n° XXX pp. 101-119 1985-1986

– Ferdinands, Rodney “Proud and prejudiced, the story of the Burghers of Sri Lanka” xii, 322 pp. ill., 32 p. of plates, maps R. Ferdinands, 1995, Melbourne, Australia. A very informative book on the Dutch Burghers community.

– Goonewardena, K “A New Netherlands in Ceylon. Dutch attempts to found a colony during the first quarter century of their power in Ceylon” Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, 1959, 2:2 pp. 203-244

– Henry, Rosita “A tulip in lotus land: the rise and decline of Dutch Burgher ethnicity in Sri Lanka” ??? Unpublished M. A. Thesis 1986, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.

– Mc Gilvray, Dennis B. “Dutch Burghers and Portuguese mechanics: Eurasian ethnicity in Sri Lanka” pp. 235-263 In “Comparative studies in society and history : an international quarterly”, Vol N° 24, 1982, Cambridge

– Orizio, Riccardo “Tribù bianche perdute: viaggio tra i dimenticati” xv+281 pp. Editori Laterza, 2000, Bari, Italia. English edition: “Lost White tribes: Journeys among the Forgotten” 281 pp. Secker & Warburg, 2000 Indice: Sri Lanka: quattro secoli di nostalgia olandese; Giamaica: gli schiavi tedeschi di Seaford Town; Brasile: via con il vento degli ultimi sudisti; Haiti: i polacchi di Papà Doc; Namibia: la Terra Promessa dei Basters; Guadalupa: i duchi della canna da zucchero. The author investigates: the Dutch Burghers of Sri Lanka; the Germans of Seaford Town (Jamaica); the Confederados of Brazil; the Poles of Haiti; the Basters of Namibia; the Blancs Matignon of Guadeloupe.

– Peacock, Olive “Minority politics in Sri Lanka: a study of the Burghers” ix, 97 pp. map Arihant Publishers, 1989, Jaipur, India.

– Roberts, M. – Ismeth, Raheem – Colin Thome, Percy “People inbetween: the Burghers and the middle class in the transformations within Sri Lanka” Vol. 1 Sarvodaya Book Publishing Services, 1989, Ratmalana, Sri Lanka.

– Thananjayarajasingham, S. & Goonatilleka, M. “A portuguese creole of the Burgher community in Sri Lanka” ??? In Journal of Indian Anthropological Society 1976, 11 (3) pp. 225-236

– Vamadevan, V. “Dutch Burghers of Jaffna” Article on “Sunday Island”, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History