This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

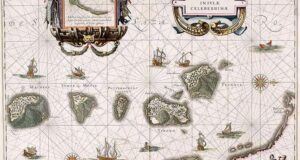

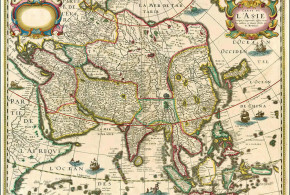

The Spaniards in the Moluccas: 1606-1663/1671-1677. The history of the Spanish presence in the spice islands

Written by Marco Ramerini. 2005-2020/23

CHAPTER TWO: THE CONQUEST OF TERNATE

THE PREPARATION OF THE EXPEDITION BY D. PEDRO DE ACUÑA

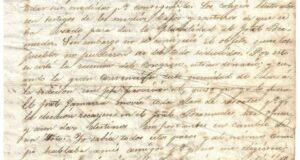

The Spanish response, this time, was not long in coming. The governor of the Philippines, D. Pedro de Acuña, in a document1, undated, present in the “General da Indias” archive of Seville, lists the reasons and benefits why the Spaniards should organize an expedition to recover the fortress of Ternate:

- The renewal of the Christian faith, both on the island of Ternate and on the nearby islands.

- The recovery of the old reputation, lost after the Portuguese were expelled from Ternate.

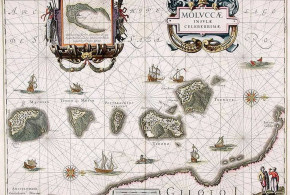

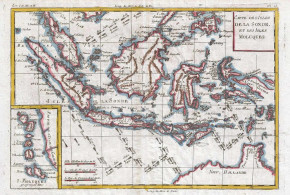

- The possibility of being able to control the trade in cloves, which only grow on these islands.2

- The benefit of being able to receive the income of the island.

- Ternate can be an excellent base to be able to occupy the islands of Mindanao and Solo, which are located along the route between Manila and Ternate.

Acuña also indicates that the secrecy and brevity of the operation are essential for the success of the enterprise, in order to catch the enemy by surprise. He recommends using Manila as a basis for preparing the enterprise, Ternate being closer and more easily accessible from Spanish possessions than from Portuguese India. Acuña’s proposal was favorably received by the King of Spain. 3

On June 19, 1604, the expedition led by Juan de Esquivel, sent by the King especially for the Ternate expedition, set sail from San Lucar de Barrameda to New Spain. 4

On February 25, 1605, a ship from New Spain arrived at the port of Cavite in the Philippines. This ship was the bearer of royal orders favorable to the expedition to be undertaken in the Moluccas, the patacco also brought information to the governor of the imminent arrival of troops from New Spain to carry out the undertaking. Two companies of soldiers also arrived in the same ship, about 200 infantry destined to participate in the expedition and sent by the Viceroy of New Spain.

The bulk of the expedition led by Juan de Esquivel had been sent directly from Spain and had departed from the port of San Lucas de Barrameda, from there it had arrived in New Spain, via Mexico City. The soldiers aboard two ships, departed from the port of Acapulco in New Spain on March 22, 1605, and arrived in the Philippines on June 9, 1605. forecasts and had also found bad weather, only one soldier died during the crossing. On board were 650 men forming part of 8 companies, 7 of which, on Acuña’s orders, had been landed in the port of Ybalon and then the following day from there transported to the island of Panay to the Villa of Arevalo (Oton) where they had been prepare food for their sustenance.

On June 18, “mestre de campo” Juan de Esquivel arrived in Manila to meet Acuña. During the seven months that Esquivel spent in Manila together with Acuña, the command of the seven companies of soldiers who had come with him from Spain and who had been sent to the island of Panay was entrusted to Lucas de Vergara. 5

Shortly after the troops arrived, 4 melted down New Spain artillery pieces also arrived aboard ship. Although the number of soldiers sent (a total of about 850 soldiers arrived) was far less than the 1,500 soldiers Acuña had requested, he was favorably impressed by the high quality of the troops sent. These troops were then supplemented by some companies of soldiers from the garrison6 and by pampangos soldiers. Acuña referring to pampangos soldiers, describes them as excellent soldiers (arquebusiers and musketeers) especially when side by side with Spanish soldiers. He also expresses his willingness to participate with his personal presence in the enterprise.

As for war material, of the 500 quintals of powder requested by Acuña, only 235 quintals of powder and 100 quintals of saltpeter were sent, Acuña complains about this, saying that he will be forced to use what is stored in the Manila warehouses. The complaints do not end there, in fact even the money sent (60,000 pesos) is a poor thing compared to the expenses to be incurred, in fact 120,000 pesos had been promised.

Knowing the favorable opinion of the king regarding the expedition he proposed in the Moluccas, Acuña immediately devoted himself to organizing the preparations, had galleys built in the shipyards of the Philippines (according to him the most effective form of defense of these islands), and at the beginning by July already 5 galleys were ready: the flagship galley had 22 seats, the “patron” galley i.e. the second in command and another galley had 19 seats each and the other two had 17 seats.

The galleys that were built were not very large and this was done mainly for two reasons, one was that of the presence of numerous coral reefs and rocks outcropping in the seas of the islands which made it difficult to use large ships, the other reason and perhaps the most important was to keep the operating costs of these ships low and therefore to do this it was decided to limit the number of rowers. The governor was very satisfied with these galleys, built thanks to the help of a skilled and experienced foreman, replaced on his death by another expert builder originally from Genoa (he had already built a galley in Cartagena).

In Manila, the capital of the Spanish possessions of the Philippines, there were also people who wanted to meddle in the organization of the expedition. In fact, Acuña criticizes the attitude held by the archbishop and by Don Antonio de Rivera Maldonado, auditor of the Audiencia, the criticism that the governor brings them is that of wanting to meddle with topics, such as those of war, of which they have no competence and which they are out of their duties.

According to the governor’s intentions, the following were to take part in the expedition: 4 of the built galleys; a large vessel (of 700 tons) for the transport of troops and provisions; a medium-sized vessel (of 250 tons); 3 light vessels (of 150 or 130 tons); 7 brigantines; 5 “lorchas”; 5 junks (vessels built as they do in China and Japan) used to transport supplies. All these boats were the ones that Acuña planned to equip on behalf of the king, in addition to these, another 7 or 8 boats equipped by private citizens had to be added. All this fleet was collected in the port of Oton in the island of Panay.

Acuña decided to leave at the head of the expedition at the end of January or the beginning of February 1606, which are the most favorable months to sail from the Philippines to the Moluccas. The priority of the expedition had to be the conquest of the island of Ternate, the intention is to make Ternate the base for the conquest of all the Moluccas and the Banda islands, in order to cut off the basis of Dutch trade at the source. 7

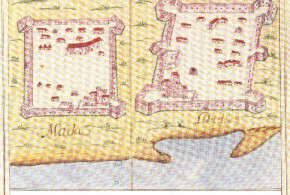

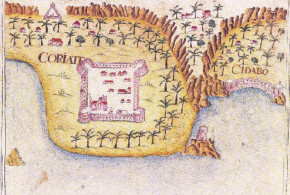

THE DUTCH CONQUEST OF AMBON AND TIDORE

Meanwhile, as we have already narrated in the first chapter, while the preparations for the expedition were taking place, the two fortresses that the Portuguese had at Tidore and Ambon were captured by the Dutch. Ambon fell without a fight on February 23, 1605 (Ash Wednesday), this seems to be mainly due to the cowardly conduct of the fortress captain Gaspar de Melo and to the personal interest of some Portuguese casados, who aimed to safeguard their assets. The Dutch rebuilt the Portuguese fort and left 130 soldiers as a garrison.

After the conquest of Ambon by the Dutch, they allowed the two Jesuits residing there (Lourenço Masonio and Gabriel Rengifo da Cruz) to remain on the island to continue their mission of evangelization. But after just over two months (“a mediado el mes de Mayo”), they changed their minds and forced the two Jesuits with 280 other people to embark on a “pequeña y mala embarcacion” for the Philippines where after thirty-nine days of navigation they landed in the island of Cebu. Father Antonio Pereira, on the other hand, continued to reside in Siao and father Jorge de Fonseca in Bachão. 8

Five of the Dutch ships which had captured Ambon then sailed to Tidore where they arrived on 5 May. The Portuguese from the fortress of Tidore, commanded by Pedro Álvares de Abreu, did not surrender at the sight of the ships, but forced the Dutch to fight, the fortress was bombarded for two days, on the third day the Dutch tried to enter the fort, but they repulsed after a hard fight, but at this point misfortune set upon the Portuguese. The key episode was the explosion of the fort’s powder magazine, which resulted in the deaths of many defenders and a huge gash in the fort walls. The few Portuguese survivors took refuge in the city of the king of Tidore, where with the help of the king of Tidore they negotiated the surrender. The Dutch gave the survivors (among them also the Jesuit Luis Fernandes, superior of the Jesuit mission of the Moluccas) some boats with which they moved to Oton on the island of Panay. 9 Tidore was conquered by the Dutch on 19 May 1605.

The Portuguese friars who had taken refuge in Manila returned to the Moluccas in 1606, with the Spanish army led by Governor D. Pedro de Acuña. 10

To better follow the preparations of the army, on October 29, 1605, Acuña arrived at the Villa de Arévalo.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE FLEET BY D. PEDRO DE ACUÑA

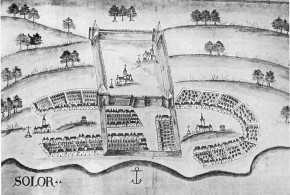

Acuña’s fleet set sail on February 15, 160611 Acuña’s fleet set sail on February 15, 1606 from the port of Iloilo (Oton, Arévalo) on the Philippine island of Panay. According to some documents, the Spanish fleet consisted of 37 boats12, on board were 1015 (mil and quinze) Spanish and Portuguese soldiers, 353 indigenous soldiers as well as 450 officers, sailors and friars (Dominicans13, Jesuits, four Franciscans and three Augustinians14). Then there were 1,330 convicts for the 4 “galés” 15. The fleet also included 3 Portuguese “galiotas”, two of which came from Malacca, with 100 Portuguese on board.16

While Esquivel in one of his letters indicates that the following 32 boats took part in the expedition: 5 “naos” or “nauios”, 4 “galés”, 12 “fragatas”, 2 “champanes”, 2 brigantines, 4 “lorchas”, 2 “ lanchas”, a boat to land artillery. 17

According to the “Relación de la Contaduría de la dicha armada, fecha en Ilo-Ilo a 12 de enero de 1606”, more precise and detailed than the other documents, the total number of men who participated in the expedition was 3,095, of which 1,423 were soldiers and Spanish sailors, 344 were Pampangos and Tagalo soldiers, 679 were Indians, 649 were rowers. 18

The Spanish soldiers were in 14 companies, 4 companies were raised in Andalusia, 8 companies were from New Spain and 2 were raised in Manila. The names of the captains of these companies were: Juan Tejo (captain of the company of the master of the field), Pascual de Alarçon, Pablo Garrucho de la Vega, Lucas de Guevara, Pedro Sevil de Grigua, Esteban de Alcazar, Martin de Esquivel, don Rodrigo de Mendoza, Pedro Delgado, Bernardino Alfonso, Cristobal de Villagra, Juan Guerra de Cervantes. The pampangos were organized into 4 companies with captains: don Guillermo, don Francisco Palaut, don Agustin Lonot and don Luis. While the Tagalos had a company of 36 men led by don Juan Lit. Again according to the same “Relación” the boats participating in the expedition were a total of 33. 19

There were 5 ships (naos): Among these the “captain” ship was the Jesús Maria of 800 tons, captained by Juan de Urbina. Then there was the ship “almiranta”, which was the 160-ton Nuestra Señora de la O., captained by D. Gil de Carranza. The other ships were the 160-ton Nuestra Señora de la Concepción captained by Nicolas de la Cueva and where Vergara had the title of chief of seafarers and war 20. The 150-ton San Idelfonso captained by Antonio Carreño de Valdés. The 100-ton Santa Ana captained by Pedro de Irala.

There were 7 galleys and galliots participating in the expedition: the “capitana” where Governor Acuña was embarked, the “Patrona”, the “Purificación”, the “San Ramón”, the “Napolitana”, the galley “San Luis” and the brigantine “San Agustín”.

Then there were 6 private boats: those of the ensign Coronilla, of Miguel de Gandia, of the “mestre de campo” of the pampangos, of the captain of the pampangos Indians don Luis Conti, of don Pedro Mendez and of the captain Juan de Gara. A lot of food had been loaded on these boats. Other ships loaded with provisions were the 5 frigates. The 2 English boats with which the Portuguese fled from Tidore had arrived in Cebú also took part in the expedition. There were 4 “funcas” (probably rushes): full of people and food. Then 3 Portuguese galliots: One was the one used by the commander of the fortress of Tidore, Pedro Alvarez de Abreu, to reach the Philippines, the other two were those captained by Captain Major João Rodrigues Camelo which had been sent by General André Furtado de Mendonça to rescue the fortress of Tidore. Finally, there was a large barge which was to be used to land artillery. The entire fleet was armed with 75 artillery pieces.

The main assignments were as follows:

General Juan Xuarez Gallinato was “del Consejo”.

Staff Sergeant Cristoval de Azcueta was Admiral of the Fleet.

The senior engineer Cristobal de Leon was captain of the honor guard of Acuña (Leon was also captain of the artillery, on his death he was appointed in his place as captain of artillery, Esteuan de Alcasar, who served in this position during the the conquest of Ternate 21.

Juan Ortiz was the “contador” of the army.

Antonio de Ordaz was treasurer of the army.

Br. Juan de Tapia was the senior chaplain of the army.

Antonio de Oliveira was a senior pilot in the army.

José Naveda was scribe of the army.

Miguel de Estrada was a doctor and major surgeon. 22

THE CROSSING AND ARRIVAL IN THE MOLUCCAS

On February 18, 1606, the fleet arrived in the port of the Caldera on the island of Mindanao, where it was stocked up on water and where an attempt was made to repair the large captain ship, the Jesús Maria, where the “mestre de campo” Juan de Esquivel was also embarked, which was in danger of sinking. But on February 21st, despite the attempts of the sailors, the leaks in the hull caused the ship to sink. However, all the artillery and ammunition it was carrying as well as all the crew were saved, the ship was burned and even the nails and bolts of the hull were recovered. Esquivel then embarked on the ship Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, which for this reason became the “captain” ship. On 26 February the fleet set sail again towards the Moluccas, with the order to gather in the port of Talangame in Ternate. 23

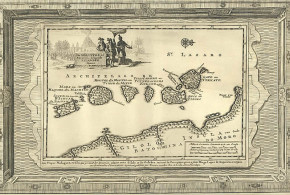

Due to the storms, the ships scattered during the crossing and arrived staggered in Tidore, only one landed by mistake in the island of Mayu, an island belonging to Ternate, and there, the Spaniards were almost all killed. In mid-March the first vessels of the fleet began arriving at Tidore.

SOME DUTCH ARE CAPTURED AT TIDORE

On the island of Tidore, the Dutch had founded a farm and left behind only a farmer and three sailors. They were captured by the Spanish without offering resistance. In the Dutch farm the Spaniards found 2,000 ducats, some merchandise and many weapons.24

On March 16, 1606, the Spanish interrogated one of the Dutch who had been captured at the Dutch farm of Tidore. The interrogation was conducted by Christoval Azcueta Minchaca, sergeant major of the regiment of the “mestre de campo” Juan de Esquivel, who was the real commander of the fleet. The Dutchman was a sailor named Joan and was a native of the city of Amberes (Antwerp), the farm factor was instead called Jacome Joan 25 and was a native of the city of Absterdaem (Amsterdam). The other two Dutchmen present were sailors, one named Pitri (Pedro Yanson, ship’s boy “San Idelfonso”26) was originally from Yncussa (Enkhuizen), the other by name (nickname) Costre 27 (Cornieles Endrique, also from the ship “San Idelfonso”28) was a native of Campem (Campen).

The interrogated, Joan, had arrived in the Moluccas with the expedition that had captured the Portuguese forts of Amboina and Tidore. He states that he had been residing in Tidore for 8 months. The factor of Tidore, Jacome Joan, on the other hand had lived in Ternate for 5 years. According to these declarations, the king of Tidore, the day after the capture of the Portuguese fort, had sworn allegiance to the Dutch and requested their protection, offering them the construction of a fort where he could station troops for the defense of the island, but since the commander29 of the Dutch fleet, which had captured the Portuguese fort did not have enough men to leave to garrison the island, at the specific request of the king it was decided to leave some Dutch in a farm to trade.

The king of Tidore, on that occasion, also undertook to defend the Dutch who remained on the island and to trade cloves exclusively with the Dutch. The Dutch then informed the Spanish of the state of war between Tidore and Ternate. Finally, he described to the Spaniards the state of the defenses of the city of Ternate: The height of the city walls was 4 “estados”, while the artillery was not inside the fort but had been stored in a house to protect it from the rain , also in defense of the city there were 2,000 warriors armed with arquebuses, muskets, “campilanes”, “petos” and “morriones”. 30

At Tidore the Spaniards witnessed a lunar eclipse. 31 There is a reference to this eclipse in Don Diego de Prado’s manuscript “…on March 22 the Moon was eclipsed in a red tending to black color, the eclipse began at 8 in the evening and ended at three in the morning. Speaking later in Ternate about this eclipse with the “mestre de campo” Juan de Esquivel he said that our army was en route to Ternate when they saw the eclipse and after the conquest of the island the Sultan of Ternate said that the ‘eclipse denoted and heralded the loss of his nation and that he was a man of great reputation in lunar matters.’ 32

The governor D. Pedro de Acuña, with the “galés”, was the last to arrive, his ships had lost their course due to a pilot error and had arrived in the island of Celebes, from here they had to fight against the currents and force of oars, arrived in Ternate on Easter day: 26 March 1606. The galleys stopped in Talangame (the port of Ternate), where they expected to find the rest of the fleet, and where instead they found a Dutch ship of 900 tons, the West-Vriesland (the captain of the vessel was a certain Gertiolfos 33, armed with 30 pieces of artillery, which was anchored in that port and with which they had a brief confrontation. Acuña was informed by some natives that the Spanish fleet was anchored in port of Tidore, which Acuña says “el Maese de Campo was in the port of Tidore that is like two leguas y media”.

On March 27 Acuña also anchored in Tidore, where he found the rest of the fleet, and where, however, the king of the island was absent.

THE SPANISH ATTACK IN TERNATE

Acuña at this point decided, wisely, after a council of war with his captains, that it was useless to waste time and strength with the Dutch ship, and it was better to launch a direct attack on the fortress. The Spaniards waited for the arrival of the king of Tidore for a few days, but then, not seeing him arrive, they decided to attack the fortress of Ternate without waiting any longer.

Acuña had decided to land his troops between the fort of Nuestra Señora and another that the Ternatese had, but a renegade’s warning not to land at that point meant that the ensign Pedro de Heredia was sent by Acuña to study the place where the Spaniards planned to land and to spy on the forts that the enemy had on the island, in order to better understand the situation and devise an accurate plan to avoid as little damage as possible to the troops during the landing. 34

On March 31, while the Spanish ships were heading towards Ternate, they met the boats with the king of Tidore35, he, eternal enemy of Ternate, promptly allied himself with the Spaniards. The Spanish troops were joined the following day by several soldiers of the king of Tidore. 36 On March 31, 1606, Acuña brought the entire fleet near the fortress of Ternate, within a cannon shot of the fort called Nuestra Señora. 37

THE LANDING IN TERNATE

The following day, 1 April 1606, half an hour after dawn, the Spaniards began to disembark. The Augustinian friar Fra Antonio Flores also took an active part in the landing, who helped the troops during the landing with a galley, shelling the enemies. The captain’s galley, on which Pedro de Heredia was embarked, was to be used during the landing of the troops to keep the Dutch ship at bay with fire artifacts, but there was no need for this. 38 Heredia did not play an active role in the ensuing battle, being aboard the galley captain.

Due to the conformation of the land along the coast, which presented only a narrow strip of land that allowed only 5 soldiers to march at a time, Acuña intelligently decided to disembark the troops trying to avoid direct confrontation with the enemies, at the time himself sent some Indians to open a path in the interior “por un monte muy espesso” with the aim of forcing the inhabitants of Ternate to divide their troops, who were entrenched in a pass along the coast, they were therefore forced for fear of being surrounded to retreat to the fort without being able to fight, leaving the pass free, the conquest of which had instead cost a lot to the troops of Furtado de Mendoça who in 1603 had attempted the conquest of Ternate.

Less than an hour after the landing, at 9 in the morning, the Spaniards arrived with their vanguard troops, led by Captain Juan Juárez (Xuárez) Gallinato, and made up of 439 nfantry companies (one of the 4 captains of the vanguard was Vergara), a musket shot (or arquebus, according to Esquivel) from the walls of the fort of Ternate. Captain Lucas de Vergara together with some soldiers, took care of the delicate task of recognizing the enemy fortifications, which according to his observations were very low and made of stone without lime, therefore not very robust and easily conquered according to his opinion. 40 Among those who took part in this recognition of enemy fortifications was also Pedro de Hermua, who was responsible for scouting the enemy defenses on the sea side especially those positioned on the Nuestra Señora baluarte. 41 The king of Tidore followed Acuña’s side as the battle progressed.

THE CONQUEST OF TERNATE

Decisive for the development of the battle seems to have been the conquest by the Spaniards of four trees where the citizens of Ternate had positioned sentries, in fact once the enemy sentries had been dislodged and Spanish soldiers in turn positioned on the trees, the sentries were very useful for moving troops quickly during battle. The soldiers in the trees with their good vision could easily warn the troops on the ground, engaged in battle, of any weaknesses in the enemy line.

Seeing that the inhabitants of Ternate were fortifying themselves on the “Cachil Tulo” baluarte, the Spaniards decided to disturb them with musketry charges and to do this better, they decided to take up an elevated position (“lugar elevado” or “sitio eminente” or “eminencia”) which was located in the immediate vicinity of the bastion, to the right of the wall in front of the “Cachil Tulo” bastion, Captain Juan de Cubas was sent for this purpose with 30 musketeers and with great difficulty managed to reach the place. In the meantime a group of Ternatese who had come out of the fort and on the sea side had attacked the Spanish troops, became aware of the Spanish manoeuvre. Then the Ternate troops impetuously attacked the small detachment commanded by Cubas. Due to the difficulty the small detachment of musketeers was in, some Spanish troops (50 “picas”, probably commanded by Vergara) rushed to the aid of the desperate captain, at this point a new sortie towards the sea was carried out by the defenders of the strong, but sentries in trees promptly warned of this move and the Spanish troops, which were probably led by Captain Cervantes, managed to halt their advance and even route them.

Other reinforcements commanded by Cristoval de Azcueta, including several arquebusier and 50 halberdiers, were then sent to reinforce Captain Juan de Cubas who continued with his men to desperately defend the conquered position. After a while the Ternatese were en route towards the city wall, so Acuña ordered his troops to attack the retreating troops and assault the walls, which the Spaniards did with great impetus, the walls were scaled and the first to reach them were the captains Juan de Cubas and Cervantes42, on this occasion, Cervantes was hit by a spear and died 5 days later, while Cubas was also wounded twice while climbing the walls, once in the chest and once in the foot. 43

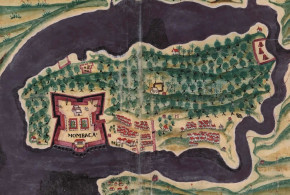

Luckily for the Spaniards, the inhabitants of Ternate did not even have the time to take refuge in the old Portuguese fort, which would have created many difficulties for the attackers, even if by the canons of the time the old Portuguese fort built in 1521 was already outdated. It is described by Argensola as “fuerza pequeña y edificada en tiempos menos maliciosos”, while Acuña defines it “pequeña y vieja”.44 Probably the lack of resistance of the inhabitants of Ternate inside the fort was due to the impetus with which the Spaniards threw themselves inside the walls of the city after the conquest of the bastion of Cachil Tulo, in particular Lucas de Vergara was the first Spaniard to enter in the main fortress, which was the house of the King (i.e. the old Portuguese fort), making the enemies flee through the windows, and placing the Spanish flag there.

Inside the fortress, ammunition and weapons were found by the Spaniards. Thanks to Vergara’s courageous conduct, even the Ternatese’s last chances of resistance were swept away. Vergara thanks to his courage and his conduct was appointed sergeant major of the Ternate camp, it seems that this assignment was initially for sergeant major Azcueta, but by choice of Acuña it was entrusted to Vergara. 45

The final battle, described above, lasted about half an hour, and an hour and a half after noon46 the fortress and the city of Ternate fell into Spanish hands. The conquest of the fortress, considered very difficult given the results of the previous Spanish expeditions, caused the loss of only fifteen soldiers while 20 were wounded. The Spaniards didn’t even land the artillery to take Ternate. 47

As regards the final conduct of the assault on the fortress of Ternate, there are two conflicting versions. The first is the one provided by the Spaniards and described above.

The second version, is the Portuguese version. According to the Portuguese, it was the Portuguese captain João Rodrigues Camelo who led the vanguard, he and the Portuguese soldiers following him captured the fortress by themselves.48 There could be something true, Argensola tells us that Acuña gave the Portuguese captains gold chains for the value they showed in the taking of the city.49 This indicates that the contribution of the Portuguese in the conquest of the city was still important.

The small Portuguese company led by Camelo, after the conquest of Ternate, returned to Malacca where it arrived in July 1606, however they found the city besieged by Dutch boats, so they were forced to attempt a landing in the bush near the city, but here most of the men were killed or captured by the Dutch, of the 52 returned from Ternate only 25 managed to reach Malacca. 50

Most probably it was Camelo and his Portuguese who brought to Malacca the letter written by Acuña to the King and dated Ternate, 8 April 1606: “y ofreciéndose unas galeotas para Malaca no he querido dexar de escrivir en ellas estos renglones, para que Vuestra Magestad sepa este buen suceso”.

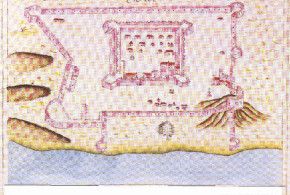

The Spaniards found in the fortress of Ternate, 43 “piezas grandes de bronce”51 “peças de colher”, more than 20 “falcões” and a large number of “berços”. Much of the artillery found was of Portuguese origin, most likely that captured by the Ternatese in 1575, but there was also artillery of Dutch and Danish origin. The condition of the fortress was not the best in this regard and the Spanish planned to immediately improve its defenses.52

The Spaniards, due to the rapid conquest of the fortress and the few dead among their soldiers, cried to the miracle by supporting the intervention of the hand of the Madonna in these events. 53

Also in Ternate the Dutch had established a farm which was occupied by the Spaniards. In this case two Dutchmen were captured.54

The city was sacked by the Spaniards.

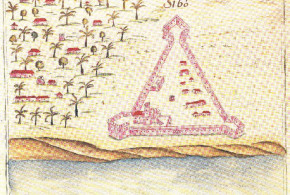

THE ESCAPE OF THE SULTAN OF TERNATE

The Sultan of Ternate, Said Berkat (his full name was as follows: Paduka Sri Sultan Said ud-din Barakat Shah), who was born in 1563, and had become the Sultan of Ternate upon the death of his father (Paduka Sri Sultan Babu ‘llah ibni al-Marhum Sultan Hairun) on May 25, 158355, he managed to escape, aboard a “caracoa”, in the fort of Sabubú in Geilolo, on the island of Halmahera (Batachina). Even some Dutch (it seems 13 or 14) who had participated in the battle fled to safety. After the Spanish conquest the Dutch ship also fled.

Friar Antonio Flores, who with his galley had received the task of supervising the caracoas that the inhabitants of Ternate had protected from the coral reef in front of the city, was unable to stop the flight of the 4 caracoas where the king had taken refuge, who managed to escape thanks to the greater speed of the boats, and also due to the onset of night. 56

The remains of the Ternate troops took refuge in the fort of Tacome (Takome or Takomi) on the NW coast of Ternate, where they were joined, on April 3, by the Spanish troops led by Captain Cristobal de Villagrá and some “caracoras” of the king of Tidore, Kaicil Mole, ally of the Spanish. Here the Kaicil Hamja and other dignitaries of the Ternate court along with some Dutch submitted to the Spanish.

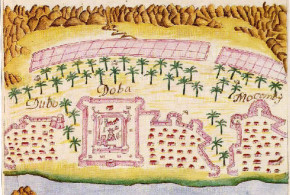

On April 2, an altar was erected and with a solemn religious demonstration the governor Acuña baptized the city of Ternate as Ciudad del Rosario (Nuestra Señora del Rrosario de Terrenate) and the main fort as fort of the Rosario, moreover it was established on that occasion the Brotherhood of the Rosary (Confradía de Nuestra Señora del Rosario). The promise made by Acuña, before the departure of the expedition from Otón, to call the first city captured from the enemy “ciudad del Rosario” was thus kept. 57

THE SURRENDER OF THE SULTAN OF TERNATE

Acuña then sent Captain Cristobal de Villagrá with the Kaicil Hamja (Amuja) accompanied by Paulo de Lima, a Portuguese “natural destas islas” (native of Ternate), to Geilolo to negotiate with the sultan. They managed to convince Said Berkat (called by the Spaniards Sultán Zaide) to submit to the Spaniards and to present himself at the castle of Ternate, which he did on April 9, 1606, accompanied by his son and heir, and many of his dignitaries.

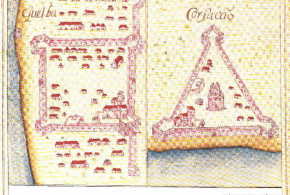

On April 10 in the fortress of Ternate, the sultan of Ternate signed the capitulations58 with which he handed over to the Spaniards the fortresses he possessed: Xilolo (Jilolo), Sabubú, Gamocanora, Tacome, the forts of Maquién, the forts of Sula “e las demás”, the forts mentioned were to be handed over to the Spaniards with all the weapons and the ammunition. All the villages of Batachina del Moro (Halmahera) as well as the islands of Morotai (Marotay) and Herrao also passed to Spain. The sultan made an act of vassalage to the King of Spain. To put these capitulations into practice, the sultan undertook to send his cousin, the cachil Amuja, to the places indicated above, together with the Spanish troops. The capitulations were signed by Sultan Zaide, by captains Juan Xuárez Gallinato and Cristóbal de Villagra and by the Portuguese “natural destas yslas” Paulo de Lima who acted as interpreter.

In execution of these agreements, two galleys left Ternate with Captain Cristóbal de Villagrá and the soldiers of his company on board as well as part of the company of the deceased Cervantes together with the prince of Ternate cachil Amuja. The two galleys first went to the fortresses of Tacome (Tacame) and Sula on the island of Ternate and formally took possession of them on 13 April 160659. Then they went to the island of Halmahera where, on April 14, the fortress of Xilolo was taken, on April 17, Sabubú was also taken and finally on April 19, Gamocanora.60

After the fort of Ternate fell into Spanish hands, the kings of Tidore, Bacan and the sangace of Alabua (Labuha, vassal of the king of Bachan) stipulated vassalage treaties with the Spaniards, in these treaties favorable conditions were recognized to the Christian religion.61

The Spaniards returned to those who had shown loyalty to them, namely the kings of Tidore, Bachan and Siao and also to Paulo de Lima (who had helped them in the negotiations with the sultan of Ternate), their possessions in the nearby islands.62 In addition to the eight villages of Makian that had belonged to Tidore, the king of Tidore was also granted the 9 villages of the island of Maquién that belonged to Ternate. While the king of Bachán was granted the islands of Cayoa, Adoba and Bailora and places in the vicinity of Amboino (Lucobata, Palomata and others). The Christian sangage of Labua, Ruy Pereira, was given possession of the island and village of Gane, located in the vicinity of Labua and birthplace of the same sangage. 63 The sultan of Tidore offered submission to Spain and also promised to have a Spanish fortress built at Tidore. 100 men under the command of Captain Alarcón were left to garrison the island of Tidore.64

The church that the Portuguese Jesuits had had in Ternate was returned to them, it was made of stone and lime and in good condition (even if it was roofless and full of earth and rubbish65). This church was the old Portuguese church of São Paulo (San Pablo), which had been equipped with an embankment by the inhabitants of Ternate to better defend itself from the Spaniards.66 While the Jesuit house is in very bad condition and according to the letter of Friar Lorenzo Masonio, it will have to be “rinnovata dai cementi”.67 The church is described as large and capable, it will be equipped, in the following years, with a spacious choir decorated with a large and beautiful gilded shrine with a silver case. 68

After the conquest, a Dominican friar, Andrés de Santo Domingo, remained in Ternate; two Franciscan friars, friar Alonso Guerrero and lay brother Diego de Santa Maria69; four Jesuits and a lay friar (Luis Fernades, Gabriel Rengifo da Cruz, Jorge de Fonseca, Lorenzo Masonio and the layman Giampaolo Mafrida), while a fifth Jesuit, friar Antonio Pereira resides in Siau.70 Two Augustinians also remained in Ternate, they were friar Juan de Tapia and the lay friar Antonio Flores.71 Among the Augustinians, friar Roque de Barrionuevo should also have remained in Ternate, who will hold the position of prior of Ternate until 1608, he also wrote a dictionary of the dialect of the Mardicas. 72

The two Franciscan friars, one of whom, friar Alonso Guerrero is a surgeon, were entrusted with the hospital of Ternate which was installed in the main mosque of the city where the convent of the Franciscan friars was also founded. While a house of a sister of the king is used for the Augustinian convent, finally the Dominicans settle in a house of a rich cachil.73

The presence in Ternate of the Portuguese Jesuits, who had taken refuge in Manila after the last Portuguese fortresses of Tidore and Ambon fell into the hands of the Dutch, represents the only official link left with Portugal, in fact they were still subjects to the Padroado of the Portuguese crown.

Some of the Jesuits dedicated themselves to the conversion of the inhabitants and to the care of the Christians of the islands near Ternate. Friar Antonio Pereira takes care of the island of Siau where he resides; while friar Jorge de Fonseca resides in Labuha (Bachan). Friar Lorenzo Masonio visits the island of Moro, while Friar Gabriel Rengifo da Cruz is shipwrecked when he is on his way to Ambon. Only the superior Luis Fernandes remained in Ternate with his lay brother Giampaolo Mafrida..74

After the conquest Acuña decided, for greater security, to deport the sultan to Manila with the prince, his son, and all his dignitaries, a total of about thirty people.75 The governor’s decision was communicated to the sultan (who was in jail the “Purificación”) on May 1, 1606 by the Jesuit Luis Fernándes. 76 The government of the sultanate was entrusted by the exiled sultan to two of his uncles (cachil Sugui and cachil Quipat) who were appointed governors.77

The sultan Said Berkat of Ternate, who, after the Spanish victory (1606) was deported to Manila, returned to Ternate in 1611 together with the governor Juan de Silva, who hoped with his presence to convince the Ternatese to ally with Spain and thus eliminate the Dutch from the Moluccas. This did not happen and the sultan was again brought back, as we shall see, to Manila in 1615, where he will remain until his death in 1628.78

INDEX

1: The first contacts of the Spaniards with the Moluccas

2: The conquest of Ternate

3: The government of Juan de Esquivel, May 1606-March 1609

4: The government of Lucas de Vergara Gabiria (acting the functions), March 1609-February 1610

5: The government of Cristóbal de Azcueta Menchaca (who performs the duties), February 1610-March 1612

6: The government of D. Jerónimo de Silva, March 1612-April 1617

7: The government of Lucas de Vergara (Bergara) Gabiria (second term), April 1617-February 1620

8: The government of D. Luis de Bracamonte (who performs the functions), February 1620-1623

9: The government of Pedro de Heredia, 1623-1636

10: The government of D. Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola (who performs the functions), March (?) 1636-January 1640

11: The last Spanish governors of the Moluccas

12: Bibliography

NOTES:

1 (Audiencia das Filipinas, Secular Legajo n°1, Doc. 43 “Pontos que D. Pedro de Acuña assinala para que Sua Majestade mande fazer a jornada das ilhas Molucas e as causas que há para assim se fazer, como também o que é necessário para a execução delas, e a utilidade e beneficios que dela se obteriam.”)

2 One hundred years after the arrival of the Portuguese, the production of cloves had also spread to other islands, especially Ambon, the western part of Ceram and the island of Halmahera, so the 5 original islands no longer enjoyed the exclusive to this spice. (Prakash, Om “Restrictive trading regimes: VOC and the Asian spice trade in the seventeenth century” In: “An expanding world” vol. 11, p. 320)(De Silva, C. R. “The Portuguese and the trade in cloves in Asia during the sixteenth century” In: An expanding world vol. 11, p. 265)

3 See: “Carta del Re ad Acuña, Valladolid, 20 June 1604” in which Acuña is ordered to make the shipment to Ternate. Cited in Esquivel’s letter: (AGI: Patronato, 47, R.22 “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey progresos islas del Maluco, 31-03-1607”)

4 (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2)

5 (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey,llegada a Filipinas, 06-07-1605” Patronato,47,R.1) (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12)).

6 There will be 250 soldiers from the Manila garrison who will take part in the expedition (Letter by Don Agustín de Arceo al Re, 10 July 1606 published in Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo V, p. ccxvi)

7 (“Letter by Acuña a Felipe III, Manila 1 July 1605” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 14, pp. 53-63)

(AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey,llegada a Filipinas, 06-07-1605” Patronato,47,R.1)

8 (Doc.Mal. III p. 51 Doc. n°11) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 17-19)

9 (Doc.Mal. III p. 49 Doc. n°10) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III pp. 20-22) (AGI: “Carta de Acuña sobre toma de Tidore por los holandeses, 06-01-1606” Filipinas,7,R.1,N.29)

10 (Doc.Mal. III p. 53 Doc. n°12)

11 (Doc.Mal III p. 2 Doc. n°1), (“Letter by Acuña al Re, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxvii-ccxix), (“Letter by Juan de Esquivel al Re, 9 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxvii) (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2). While erroneously, the departure date is January 15 according to: (Argensola p. 322) e (Pérez p.682)

12 36 boats according to: (Doc.Mal. III p. 15 Doc. n°3)

13 As reported by friar Diego Aduarte in his “Historia…” the Dominicans who took part in the expedition were friar Andres de Santo Domingo and a lay religious. (Aduarte, Diego “Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 31, p. 247)

14 The Augustinians were: friar Roque de Barrionuevo, friar Juan de Tapia and the lay friar Antonio Flores. Friar Roque de Barrionuevo was entrusted with the task of founding an Augustinian monastery in Ternate, he was also appointed prior of Ternate, a position he held until 1608. (Wessels “De Augustijnen in de Molukken” pp. 55-56)

15 (Francisco de Romanico was “general” of one of these galleys (AGI: “Informaciones Fernando Centeno Maldonado, 1615” Filipinas,60,N.18))

16 (Doc.Mal III pp. 2-3 Doc. n°1)

17 (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2)

18 (“Relación de la Contaduría de la dicha armada, fecha en Ilo-Ilo a 12 de enero de 1606”)

19 (“Relación de la Contaduría de la dicha armada, fecha en Ilo-Ilo a 12 de enero de 1606”)

20 (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12)

21 Vedi: (AGI: “Parecer de la Audiencia sobre Esteban de Alcazar, 07-08-1615” Filipinas,20,R.9,N.57) (AGI: “Confirmación de encomienda de Hagonoy, etc. Esteban de Alcazar. Manila, 21-10-1616” Filipinas,47,N.5 ) (AGI: “Meritos Esteban de Alcázar, 1623-07-19” Indiferente,161,N.81))

22 (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxliii-ccxlv “Relación de la Contaduría de la dicha armada, fecha en Ilo-Ilo a 12 de enero de 1606”)

23 (“Letter by Juan de Esquivel al Re, 9 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxvii) (“Letter by Acuña al Re, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxvii-ccxix) (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12 in particular the testimony of the Augustinian friar Antonio Flores) (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2).

24 (“Letter by Acuña al Re, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxvii-ccxix), (Montero y Vidal p. 151) and also (Turbolent times p. 132), according to Diego Aduarte there were two Dutchmen found on the Tidore farm (Aduarte, Diego “Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 31, p. 249).

25 (Jácome Jolián in the version of the same interrogation given by Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxx)

26 (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxix)

27 (or Postre in the version of the same interrogation given by Pastells (“Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxx)

28 (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxix)

29 The name of the Dutch fleet commander is Cornieles Bastian

30 (“The Dutch factory at Tidore” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 14, pp. 112-118) (See also the version of the same document given by Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxx-ccxxi))

31 (Aduarte, Diego “Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 31, p. 249)

32 (Prado “The discovery of Australia” p. 7)

33 (“The Dutch factory at Tidore” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 14, p. 114)

34 (AGI: “Parecer de la Audiencia sobre Pedro de Heredia, 20-07-1612” Filipinas,20,R.6,N.50) (AGI: “Meritos Pedro de Heredia, 22-09-1628” Indiferente,111,N.78)

35 (Pérez p. 683)

36 (“Letter by Acuña to the king, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxvii-ccxix)

37 (“Letter by Juan de Esquivel to the king, 9 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxvii) (AGI: “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2)

38 (AGI: “Parecer de la Audiencia sobre Pedro de Heredia, 20-07-1612” Filipinas,20,R.6,N.50)

39 5 companies made up the avant-garde according to the testimonies of Esquivel and Azqueta in: (AGI “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc Pedro de Hermua, 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28”)

40 (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12)

41 (AGI “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc Pedro de Hermua, 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28”)

42 This according to Argensola, while according to the testimony of the governor Acuña, the first Spaniards who entered the fortress were the Spanish captains Juan Guerra de Cervantes and Cristóbal de Villagra. (Colin-Pastells III, pp. 46-47 citato in: Doc.Mal. III p. 88)

43 (“Relación de méritos y servicios del Capitán Juan de Cubas” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxv)

44 For the narrative of the battle are useful sources: (Argensola pp. 326-329) (“Letter by Acuña to the king, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxi-ccxxiv) (“Letter by Esquivel to the king” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxiv-ccxxv) (Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 320 nota n°1)

45 See the testimony of the Augustinian Fra Rroque de Barrio Nuebo in: (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12))

46 (Doc.Mal. III p. 11 Doc. n°2)

47 (“Letter by Acuña to the king, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxiii) (“Lettera di Esquivel al Re” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxiv-ccxxv)

48 (Doc.Mal. III p. 88-89 Doc. n°24)

49 (Argensola pp. 332)

50 (Boxer-Vasconcelos “André Furtado de Mendonça” p. 66)

51 (Argensola p. 329) and also (“Letter by Acuña to the king, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxiii) mentre in Doc.Mal. III p. 8 Doc. n°1: “40 peças de colher”, more than 20 “falcões” and a large number of “berços”.

52 (Doc.Mal. III p. 8 Doc. n°1) (For a detailed list of the artillery found in Ternate see: Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxvii-ccxxviii)

53 (For the miracles attributed to the Madonna in this battle see: Aduarte, Diego “Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 31, pp. 251-252)

54 (Montero y Vidal p. 151) (“Letter by Acuña to the king, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxix) (Doc.Mal. III pp. 7-10 Doc. n°1)

55 Source: Christopher Buyers “Royal Arch”

56 (AGI: “Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12)

57 (Doc.Mal. III p. 338 Doc. n°91 & nota 1) (Aduarte, Diego “Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario” In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 31, p. 251) (“Información de Azcueta, 1609” in: Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxx-ccxxxi)

58 See: Doc. 7027Archivo de Indias di Siviglia “Capitulaciones que por disposición del general de esta armada Don Pedro de Acuña hicieron con el rey de Terrenate el General Juan Juárez Gallinato y el capitán Cristóbal de Villagra. Fortaleza de Terrenate, 10 de abril [1606]” . 1-2-1/14, r.o 5 (fs. 109)

59 See: Doc. 7028 dell’Archivio de Indias di Siviglia “Posesión que en nombre de S. M. tomó el general Juan Juárez Gallinato de Terrenate, su fortaleza y otros pueblos sus anexos, cuya posesión tomó con todas las solemnidades en el pueblo de Tacame, por disposición del general de esta armada Don Pedro de Acuña. 13 de abril [1606]” . 1-2-1/14, r.o 7. (fs. 109)

60 (Argensola pp. 337-342) (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxvii)

61 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 117 Doc. n°35) (AGI: “Carta de Ruy Pereira Sangage al Rey de España, 2-05-1606” Patronato,47,R.16)

62 (Argensola pp. 342-343)

63 (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxviii) (AGI: “Carta de Ruy Pereira Sangage al Rey de España, 2-05-1606” Patronato,47,R.16. In questo documento è presente anche la carta firmata da Acuña che concede al Sangage il possesso dell’isola di Gane, datata: “Parecer de don Pedro de Acuña sobre la conducta y persona de Ruy Pereira Sangage, Terrenate, 2-05-1606”)

64 (Montero y Vidal p. 151) e anche (Turbolent times p. 132)

65 (Doc. Mal. III p. 218 Doc. n°59) (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxviii)

66 (Argensola p. 329)

67 (Doc.Mal. III p. 12 Doc. n°2)

68 (Doc. Mal. III p. 218-219 Doc. n°59)

69 (Doc.Mal. III p. 23 Doc. n°3)

70 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 8-9 Doc. n°1)

71 (Doc.Mal. III p. 23 Doc. n°3) (Concerning Juan de Tapia see also: Fr. Juan de Medina “History of the Agustinian order in the Filipinas Islands” 1630 (pubblicato: 1893, Manila) In: Blair vol. 24, p. 109; where the friar is described as being not only a very good friar but also a valiant soldier) (For the lay brother Antonio Flores, see Argensola pp. 299-300 and Wessels “De augustijnen in de Molukken” p. 56)

72 The Mardicas (in portuguese, mardicas; in dutch, Mardijker) were a community formed by Portuguese natives and mixed blood. They spoke a creole language of Portuguese origin. (Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 24 p. 41 nota 10)

73 (Argensola p. 343)

74 (Doc.Mal. III p. 23 Doc. n°3 & p. 27 Doc. n°4)

75 (Doc.Mal. III pp. 2-7 Doc. n°1) The following dignitaries were deported to Manila: the Sultan of Ternate, Cachil Sultan Zaide Burey; the son of the sultan and his heir, Cachil Sulamp; Cachil Tulo; the son of the Cachil Tulo, Cachil Cidase (?); Cachil Amura cousin of the sultan; Cachil Ale; Cachil Naya; Cachil Colanbaboa; Cachil de Rebas; Cachil Pamuia; Cachil Babada; Cachil Barcat; Cachil Suguir; Cachil Gugugu; Cachil Bulefe; the Sangage of Bachan, Bulila; Cachil Maleyto; the Sangage of Maquien; the Sangage of Lacomaconora; besides two other Cachis who were considered as priests and three servants. (AGI: “Capitulaciones con el rey de Terrenate, 1606” Patronato,47,R.11)

76 (Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, p. ccxxviii)

77 (Argensola p. 344)

78 (Doc.Mal. III p. 5*)

This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History