This post is also available in:

![]() Português

Português

Written by Fransisco Soarez Pati, S.H

Email: fransisco78@gmail.com

Photos by Fransisco Soarez Pati, S.H

Paga is a sub district in Sikka district, Flores island on East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia. This area is still included in the Lio ethnic area, which borders with Ende District in the west part. The local mythology tells that Paga comes from the word of “Pagão”, given by the Portuguese which means worshiping idols.

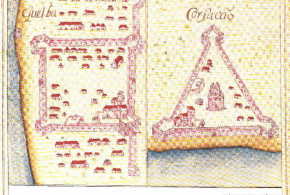

Since at the ancient times the Portuguese footprint in Paga has only been known through the da Costa clan. Recognize it or not recognize, the history of the Portuguese colonial presence in Sikka district, Flores island on East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia was dominated by the stories about the Portuguese presence in a small village called Sikka. In the middle of February 2014, a Portuguese website “Journal de Noticias” based in Lisbon published an article with the title “Descendentes Do Rei De Sica Querem Museu Para Tesouro Português“, which mean Descendants of the King of Sikka Want a Museum for Portuguese Tresure. I don’t know why the modern generation of today is just imagining whether it’s true or not that the Portuguese colonial had left its mark on Paga.

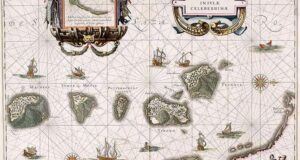

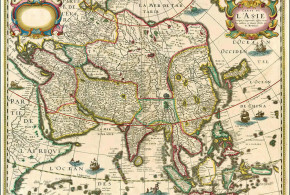

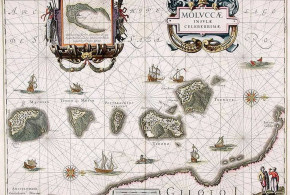

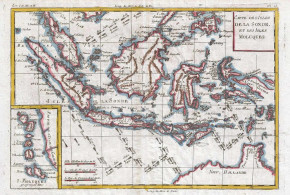

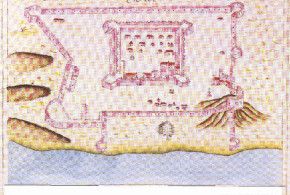

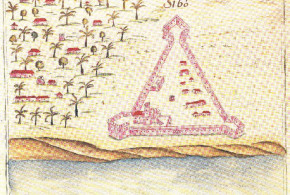

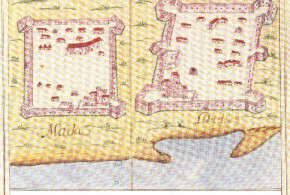

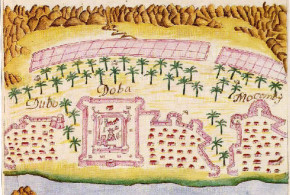

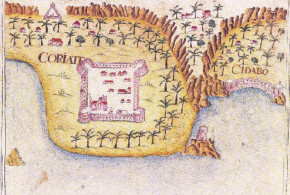

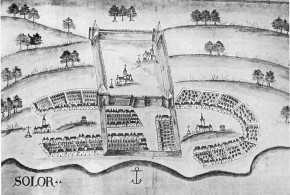

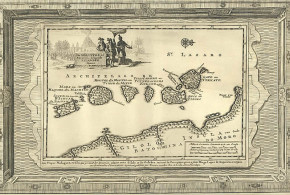

Paga is a Portuguese colonial territory in the south part of the island of Flores, Indonesia. During the times of Portuguese heyday in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, most of all areas in the Flores archipelago that were influenced or had traces of Portuguese colonialism were generally located on the southern side of the island. Starting from the Solor island, Adonara island, Larantuka, Sikka, Paga and Ende island, all of them are all located in the southern coastal area of the Savu Sea. At that time Ende island known as Ilha Grande (Big Island) to replace Nusa Eru Mbinge as the island’s original name.

Meanwhile, on the northern side of the island of Flores, the Portuguese do not have any traces of colonialism except for the names of Kewa (Queva) and Dondo given by dominican missionaries in the sixteenth century. On the northern side of the island of Flores, there was also a place that was visited by Saint Francis Xavier. Located 12 km from Maumere, the place is believed to have been passed down from generation to generation as the place where Saint Francis Xavier first stopped in Flores island to fill up supplies which later became known as “Wair Noke Rua” which means spring of saint.

The main reason why the Portuguese controlled the southern coast of the island of Flores was because by controlling the southern coast of the island of Flores, the Portuguese could be easily sail to island of Timor who separated only by the Savu Sea, which had white sandalwood which was very expensive in the European market at that time.

A number of Portuguese colonial history writers such as Francisco Vieira de Figuierido who wrote the book Portugues Merchant Adventure In South East Asia 1624-1667, Fernando Figuerido with his work Timor, A Presence Portugesa, Isabel Boavida with her writing A Presenca Portuguesa No Pasifico. A Missionação, No Preceso Colonial de Timor O E Seu Patrimonio Arqueitecnico Hoje (Portuguese Presence in the Pacific. Mission, In the Early Colonial Era of Timor and Its Architectural Heritage Today) or Hans Hagerdald through his work entitled Lord of the Sea, Lord Of the Land, Conflict And Adaptation In Early Colonial Timor, 1600-1800, almost never write a story regarding the Portuguese presence in Paga and Ende Island.

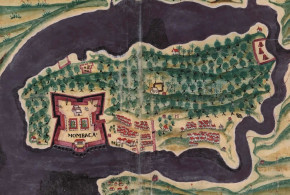

A report file or journal released by Australian National University, quote writing of Visser’s report “that Paga in the south-western reaches of Kabupaten Sikka and Sikka Natar itself were the sites of such stations on the south coast. While there is only a vague tradition among the contemporary people of Sikka Natar that their village was the site of a Dominican mission station, as Visser reports, it is possible that the village was, if not a Dominican station, then at least a place visited more or less regularly by Dominicans embarked on the Portuguese ships that passed along Flores’s south coast”. Whereas the historical of the Portuguese presence on the island of Timor cannot be separated from the Portuguese presence on the island of Flores and its surroundings, even the first Portuguese colonial center in Flores, Solor and Timor was on the island of Solor, in East Nusa Tenggara province, Indonesia before finally Portuguese being moved to Lifau and in 1769 it was moved again to Dili which later became the capital of the state of Timor Leste. In Paga today there are no traces as reported by Visser, except for a vacant lot which local people believed as a place that the Church was founded by the Portuguese and so on which will be written in this article.

Apart from the absence of written Portuguese colonialism footprint in Paga by the authors above, if the readers of this article are related by blood or marriage or friendship or at least have visited Paga, then in Paga we can easily see that some of the Paga people today have different physical characteristics from most Florinese people in general. Strong suspicion that they are of Portuguese descent which is not written in Portuguese colonial history.

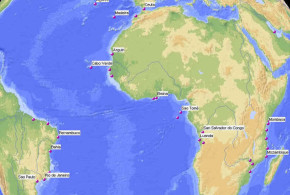

The main reason why the Portuguese always married local women in the terra coloni as a new homeland was because after the Portuguese signing of the Tordesillas Treaty (Tratado Torsesilllas) on 7th June 1494, a new land division agreement, nova terra in Portuguese or nueva tierra in Spanish was found outside Europe between the Portuguese and Castilla (Spain), then the Portugal were given the freedom to fully control all regions outside Europe along the 370 League Meridian line through Cape Verde, South Africa to the east, while Spain controlled the entire west area of Cape Verde towards the Americas .

After the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas, then the Portuguese implemented a political strategy called politica asimilados or cassados and moradores, a political strategy by intermarry with local women or king’s daughter so that their presence in terra colonial what they called as new a homeland, received support from the local community or the local king. A new factor in the make-up of Florinese/Solorese population concerned Portuguese men who came to these waters with an intention of becoming part of the profit-making trade in spice, sandalwood and slaves. Some decided to settle permanently cohabit with slava girls married into the local families. Under Portuguese law these settlers were terned casados or moradores, forming the blackbone of Portuguese settlements, supporting Portugueses trading and missionary activites. Under the Portuguese law they were Portuguese, Christian by religion and bore a Portuguese family name. When the Portuguese had leave this area in the 17th century and the Dutch endeavoured to incorporate it into their sphere of activity, the Mestizos may have played the role of intepreter between the Dutch and the Portugueses speaking local comunity. The King of Portugal through the Dereito Real de Portuguese on March 15, 1538 then gave a special grant to Portuguese men, who were married and settled and cultivated a new homeland (terra novo) outside of Europe, giving privileges to Portuguese men who carried out missions overseas. By taking root in their new homelands they would at the same time roots for Portuguese interest.

The descendants of the Portuguese marriage who used the strategy of “politica asimilados or cassados” were later called Topass or Mestizo which means Black Portuguese (Black Portuguese) meanwhile the Dutch call it as the Portuguese Zwart. The Portuguese political strategy was very different from and with the Dutch political strategy known as Devide et Impera or divisive politics.

Mateo da Costa and Antony da Hornai da costa are two brothers born from the marriage of a Portuguese citizen with a Larantuka woman. These two figures later formed a group called “Larantuqueros” which means the Larantuka people, a group that was considered dangerous and feared by the Portuguese and the Dutch. Jacob van der Hijden, the commander of the Dutch troops of Solor and Timor who had conquered the Sonbai kingdom, died at the tip of Antony a Hornay da Costa’s sword .

Beside leaving the da Costa clan in Paga, there is also a stone grave which in the Lionese language is called “Musu Mase” in Paga. Locals believe for generations that the stone grave is where the heads and bodies of two Portuguese men were buried after being beheaded by Antony da Costa, a brave local resident of Portuguese descent. This generation of Antoni da Costa or known as Mamo Ndona later gave birth to Mr. Daniel Woda Palle, the former regent of Sikka (1977-1988) and the former Chairperson of the Regional People’s Representative Assembly of East Nusa Tenggara Provincial (1999-2004). Apart from Mr. Daniel Woda Palle, genealogically the generations of Antony da Costa’s descendants are now scattered in almost all parts of Indonesia.

In addition, in Paga there is a cannon from the Portuguese heritage as well as a place on the beach which is as the place where the Portuguese first set foot in Paga and founded the Catholic Church which in local terms they called as “Gereja Manu”. Currently the Church building is no longer there and only vacant land was left in the former church building. The Bobu dance as a dance influenced by the Portuguese still maintained by the Paga people today. The description above is the de facto situation that, Paga is a forgotten Portuguese colonial territory.

Meanwhile, de jure in a document called Tratado Demarcação E Troca De Algumas Possessoes Portuguese E Neerlandezas No Archipelago De Solor E Timor which means Agreement on Demarcation and Exchange of Several Portuguese and Dutch Owners in the Solor and Timor Islands signed by Dom Pedro V and Mauricio Helderwier on April 20, 1859, the Paga area along with Sikka, Larantuka, Wureh in Adonara island, Pamong Kaju in Solor island, Lomblen, Alor and Pantar were regulated in article 7 of the agreement to be handed over by the Portuguese to the Dutch. The original text of the agreement, which was in Portuguese, reads as follows:

Artigo 7

Portugal cede a Neerlandia as possessoes seguintes :

Na ilha de Flores, os estados de Larantuca, Sicca e Paga com suas dependecias; na ilha de Adonara, o estado de Wureh, na ilha do Solor, o estado de Pamang Kaju.

Portugal desiste de todas as pretensoes que poderia talvez fazer valer sobre outros estadis ou logares, situados nas supramencionadas ilhas, ou nas de Lomblen, de Pantar e de Ombay, quer estes estados usem da bandeira portugueza, quer da neer .

It means :

Article 7

Portugal cedes to Netherlands the following possessions:

On the island of Flores, the states of Larantuca, Sicca and Paga with their dependencies; on the island of Adonara, the state of Wureh, on the island of Solor, the state of Pamang Kaju.

Portugal gives up all claims it could possibly make over other states or places located on the afore mentioned islands, or on those of Lomblen, Pantar and Ombay, whether these states use the Portuguese or Netherlands flags.

Instead, in other provisions of the agreement, the Portuguese were given the right to control the entire territory of eastern Timor (now Timor Leste), Oecuse and the island of Kambing (Ilha de Kambing) which is known as Atauro Island. The total compensation given by the Dutch to the Portuguese was 200,000 florins (ancient Dutch currency) in the amount of 80,000 florins handed over in 1851, when the Portuguese ran out of money after the transfer of their center of power from Lifau to Dili in 1769. The transfer of the Portuguese colonial center for the second time, after the defeat of the Portuguese on Solor Island with the Solor Watan Lema group or five coastal areas (Negeri Lima Pantai) namely Lohayong, Lamakera, Lamahala, Terong and Labala who received assistance from Dutch troops and the Sultanate of Ternate in North Mollucas.

Meanwhile, the remaining 120,000 florins were handed over one month after the signing of the 1859 treaty in Lisbon. At the time of the negotiations, the Dutch Parliament had objected because there was no article that gave Dutch the freedom to carry a Protestant mission (Zendeling), but the Portuguese remained in their stance that Catholicism which had been introduced to the people in Flores and its surroundings should remain the religion of the people (religiao do comunidade).

According to Karel Steenbrink in his book The Indonesian Catholics Volume I, the publisher of Ledalero, Maumere (Orang-Orang Katolik Di Indonesia, Jilid I, penerbit Ledalero, Maumere), he stated the Portuguese principle that “the flag could be changed, but the religion should not be changed. The Roman Catholic must be preserved as before. This is the reason why the majority of the people on the Flores island including Paga in East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia follow the Catholic religion until now. In the author’s opinion, although the title of the agreement is an agreement on the exchange and demarcation of colonial territories but in the context of international treaty law, the agreement between the two colonial nations is more accurately referred to as a sale and purchase agreement for the colonial territory.

As the end of this paper, it should be noted that at that time Portugal was ruled by a king named Fernando II (1837 to 1853). He then appointed Jose Joaquim Lopes de Lima as governor of a separate Portuguese colony overseas from 3 June 1851 to 15 September 1851. Jose Joaquim Lopes de Lima was then appointed Governor of the Portuguese in Macau from 15 September 1851 in charge of the entire territory of Timor, Flores, Solor, Adonara, Alor and Atauro. His position as a Portuguese Governor in Macau did not last long because he died on September 8, 1852 in Macau. It is strongly suspected that the death of Jose Joaquim Lopes de Lima in 1852 was closely related to his betrayal of the King of Portugal, who in 1851, without the King’s consent, had allied with the Dutch in the process of “negotiating” to hand over the Portuguese colonies including Paga.

This is the historical root why Paga, Sikka, Larantuka, Flores island, Adonara, Solor, Alor, Pantar and West Timor became the Dutch colonial territories. According to uti posidetis iuris principle in international law then those regions now belongs to the territorial of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI). While in the eastern part of Timor island, Oecusse and Atauro Island became the Portuguese territories and now those regions belongs to the territorial of the Republica Democratica de Timor Leste.

BIBLIOGRAPHY :

- P. Sareng Orinbao, SVD, Nusa Nipa, Nama Pribumi Pulau Flores (Warisan Purba), Nusa Indah, Ende, 1969

- Francisco Vieira de Figuierido, A Portugues Merchant Adventure In South East Asia 1624-1667, Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal – Land En Volkenkunde, Deel 52, C.R Boxer

- Fernando Augusto de Figuerido, Timor, A Presence Portugesa (1769-1945), Universida Do Porto, Faculdade De Letras, 2004

- Isabel Boavida, A Presenca Portuguesa No Pasifico. A Missionação, No Preceso Colonial de Timor O E Seu Patrimonio Arqueitecnico Hoje, Universidad de Coimbra

- Hans Hagerdal, Lord of the Sea, Lord Of the Land, Conflict And Adaptation In Early Colonial Timor, 1600-1800, Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal – Land En Volkenkunde, KITLV Press, Leiden, 2012

- (1861), Tratado Demarcação E Troca De Algumas Possessoes Portuguese E Neerlandezas No Archipelago De Solor E Timor, Entre Sua Magistrade El-Rei De Portugal E Sua Magistade El Rei De Paizes Baixos, Assignado Em Lisboa Pelos 20 Abril, 1859

- Karel Steenbrink, Orang-Orang Katolik Di Indonesia, 1808-1942, Sebuah Profil Sejarah, Jilid I, Penerbit Ledalero, Cetakan I, April, 2006.

- Paramitha A. Abdurachman, Bunga Angin Portugis di Nusantara, Jejak-Jejak Kebudayaan Portugis Di Indonesia, LIPI Press, Jakarta, 2008, Yayasan Obor, Subtitles Atakiwan, Casados, And Tupassi: Portuguese Settlement And Christian Communities In Solor And Flores (1536-1630), Indonesian Society Magazine, Year – X, No. 1, 1983

- António d’Oliveira Pinto da França, Pengaruh Portugis Di Indonesia, Cetakan Pertama, PT. Penebar Swadaya, , 2000, translated by Pericles Katoppo from the original book entitled “Portuguese Influenced in Indonesia”, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisabon, 1985,

- Pelayaran Dan Perdagangan Kawasan Laut Sawu, Awal Abad-18, Awal Abad-20, Didik Pradjoko & Friska Indah Kartika, Wedatama Widya Sastra, 2014.

This post is also available in:

![]() Português

Português

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History

Colonial Voyage The website dedicated to the Colonial History